Leading up to the 2006 Academy Award ceremony, only two films were legitimately given a shot to take home the Best Picture award: Paul Haggis’ Crash and Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain.

The presumptive favorite was Brokeback Mountain, and when Lee won Best Director for that movie, it only strengthened the argument that it would take home the night’s biggest prize. However, it was Crash that ultimately won Best Picture. At the time, it was a small upset but nothing earth-shattering.

Since that time, though, Crash has moved onto many lists of “worst Best Picture winners of all time.” The movie, a collection of intersecting storylines, all united by their examination of race relations in L.A., is seen as an over-simplified version of a complex idea. Many complain that the script relies too heavily on coincidences and stereotypes.

Nonetheless, the movie obviously resonated with many voters and members of the public. (It still has a healthy 7.8 rating from IMDb users.) The film was unafraid to confront issues that many wanted to sweep under the rug. Many of those issues are still largely at the forefront of public discourse in 2017.

The interesting thing about the criticisms leveled against Crash is that most of them are not inaccurate, simply misguided. So even though Crash’s standing has decreased in the years since its Oscar victory, below are seven reasons that Crash is better than its reputation.

1. It’s not meant to be 100% realistic

To label Crash as “allegorical” would be a little bit bombastic because the movie is not overtly symbolic. However, Haggis’ script was written to smash apart our easy-to-believe ideas that only certain people are racist and that we know who to condemn. By creating characters that are, at first, easily identifiable, Haggis and his team can set to work dissecting those identities to interesting ways.

Because the film is well-shot with excellent performances, it is judged by a standard of 100% truth, like many grittier dramas would be. That is not its intention, though. To expect that level of verisimilitude from Crash is to miss the point. Haggis’ intention was never to present reality, but a modified version that asks important questions.

2. Its coincidences are purposefully oversimplified

One standard refrain in picking apart Crash (especially its screenplay), is that it relies on wholly unbelievable coincidences. There is absolutely no doubt about that. As stated above, the movie is not meant to be entirely realistic.

The coincidences are put in the movie to allow the characters to interact in different circumstances and invite the audience to see themselves in these fictional people. Would Matt Dillon’s racist cop sexually humiliate a black couple and then have the opportunity to save her life the next day? Highly unlikely. Could two different cops, both with blatant racial prejudices, have these two experiences within a few weeks, however? Most definitely.

To simplify for the audience and ignite their thought processes, Dillon’s policeman is the one that both moments belong to. The myriad other coincidences in the movie play by the same rule: illustrating an overarching idea while sacrificing believability. A viewer can crow about the idiocy of these coincidences or can, instead, consider what it reflects in their real-life experience.

3. Regardless of its realism, it demands viewers to consider their own prejudices

As those aforementioned coincidences pile up and the expectations of the viewers are upended, those viewers are invited to think about their similar prejudicial attitudes. There is a certain self-congratulatory tone that could pervade some of the early scenes as viewers applaud themselves for being more like Ryan Phillippe’s Officer Hanson and stoke their righteous outrage for Dillon’s Officer Ryan.

Audience members are also able to laugh lightly at the banter between Ludacris’ Anthony and Larenz Tate’s Peter as they poke fun at racial stereotypes while also acting in ways that reinforce them. As the beginning of the film unfolds, there is little discomfort for the audience. Characters behave in expected ways and are perceived as the viewers would perceive them.

Once that bubble is burst, though, and the characters begin to symbolically “crash” into one another, the likelihood is that every viewer feels some unease, realizing that they, too, are not who they pretend to be. Obvious, exterior biases are harder to hide and easier to find the strength to overcome. Deep-seated bigotry, hidden beneath the surface, is much more difficult to confront, especially because people pretend it does not exist.

As the characters most easily identified with become the characters that do unspeakable things, so the audience considers the possibility that their concealed intolerance may rear its ugly head when they least expect it. That invitation to thought is one of the most important consequences of watching Crash. It is not a movie that rewards passivity; in fact, it demands accountability.

4. It benefits from its unwillingness to paint any one character as 100% hero or 100% villain

Fiction has a tendency to paint its heroes and villains with broad strokes. Oftentimes, it allows readers and viewers to more easily identify who is who and find the person most like them. To fully engage an audience, though, the complexities of human experience and thought must be represented.

Here, Haggis and his team don’t let anyone be the shining beacon of purity. Unlike the recent Hacksaw Ridge, where Andrew Garfield’s Desmond Doss was basically sainthood personified, the characters who populate Crash are incredibly flawed and unable to live by the code of morals they profess.

One of the smartest moves the script makes is not just allowing the villains to atone in some way for their sins, but also delving into the latent leanings of the supposed heroes. It not only forces introspection from the viewers but helps to expose the weighty failings of the black and white lens through which many view our world.

As it is easier for fiction to paint with broad strokes, it is easier in reality as well. One may wish the world to be an eternal if/then statement, where one knows exactly what will happen based on cause and effect. That is so far from the truth.

5. It uses stereotypes so that the audience can examine the accuracy of stereotypes

Obviously, Crash is populated with stereotypes (both situationally and in regards to people). As briefly mentioned above, the first half of the movie sets up the stereotypes so that the second half of the movie can deconstruct them, therefore helping to deconstruct the stereotypical perspective of the members of the audience. Categorizing everyone with handy labels is much less taxing than bridging a gap with them in an effort to truly understand their intricacies.

It’s always easier to dismiss people based on a few interactions, pretending it presents a full picture. Since Crash refuses to put any individual into a pre-made, easy-to-digest box, the audience’s perspective is shown to be woefully inadequate to process actual, living, breathing, complicated human beings.

6. The performances still hold up

The cast of Crash is a great one. Featuring Don Cheadle, Sandra Bullock, Matt Dillon, Thandie Newton, Michael Pena, and Larenz Tate (among others), the cast is entirely devoted to bringing the world of Crash into sharp focus.

Even though some of the characters seem to start off as one-dimensional caricatures, the actors and actresses bring subtle depth and shading to them. With a film like Crash, which requires many ethnicities to establish its realism, casting the right people is a priority. The story is not one, necessarily, of redemption; it’s one of unflinching honesty.

Each actor or actress cannot give into the temptation to whitewash their character for the sake of audience sympathy. Sandra Bullock and Matt Dillon had notably tricky roles, rankling the audience with their characters’ flaws before allowing those viewers to glimpse their characters’ humanity (all without discounting the moral failings shown previously).

Dillon’s cop, Officer Ryan, is particularly off-putting for viewers, demonstrating despicably discriminatory practices that move from “icky” to “prosecutable” in seconds. But Dillon resists the urge to downplay anything.

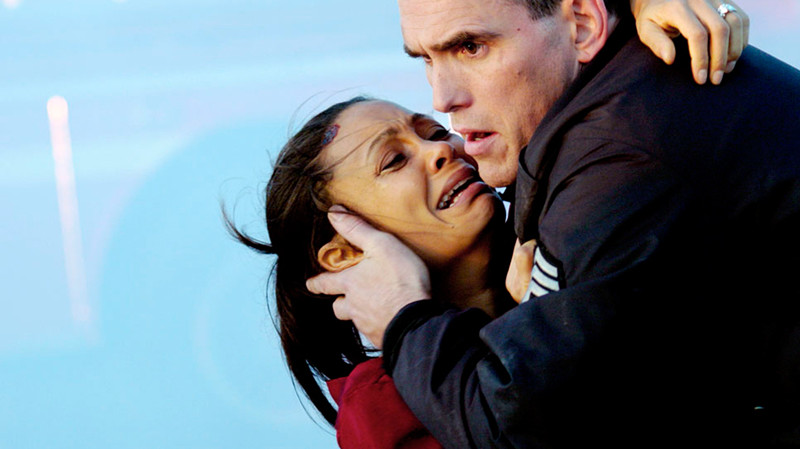

Even in his heroic scene, where he saves Thandie Newton’s Christine from an overturned vehicle, his eyes, face, and voice are loyal to the character he has established. In fact, in scenes where he is helping his father deal with the crippling and embarrassing effects of serious illness, his mannerisms communicate the same world-weary anger that exploded in the earlier scenes. Here they are just manifested differently.

Similarly, Bullock’s high-strung Jean, wife to Brendan Fraser’s District Attorney, is nigh unto unlikable in early scenes, screeching and stomping histrionically. This isn’t to say she is unbelievable: there are many people who get worked up about the same things that she does. However, it is difficult to keep the audience empathetic until she finally has a few small moments of relatability.

Ultimately, that is what highlights the performances in Crash: empathy is not their overarching goal. Complexity and humanity, those are what they were striving for. And the cast is more than up to the task.

7. It has sneaky-good, subtly powerful cinematography

This isn’t bravura camera work. James M. Muro (credited as J. Michael Muro) is not a household name and the film is not full of spectacular, not-to-be-missed compositions and long-take shots that take your breath away. However, Muro’s artfully employed close-ups and surprising choices add to the movie’s efficacy. Take a scene like the one in which Don Cheadle’s character, Graham, is conversing with William Fichtner’s Flanagan.

The subject is a promotion for Graham as well as leniency towards Graham’s brother’s criminal record. After some initial, slightly awkward expository dialogue (the dialogue sometimes sets up the racial tensions and/or complexities in stiff ways before giving way to a more naturalistic and effective approach), Flanagan sets the terms for what he wants Graham to do.

It’s an important moment for the movie and for Graham. The tendency might be to over-utilize close-ups in this scene, thereby maximizing the emotional resonance and allowing Cheadle and Fichtner to be more subtle in their acting. However, Muro resists the temptation, settling for something more effective, yes, but less obvious.

In echoing the tightness that Graham begins to feel, Muro moves slowly closer, shots at a time, as Graham feels he has no choice but to agree. When Graham’s mind is ping-ponging around as he considers the options and reasons for agreeing vs. not, we are close enough to see Cheadle’s face and eyes cycle through the possibilities and understand what needs to be done.

It seems a backhanded compliment to single out this scene while simultaneously acknowledging that it is nothing special. Haggis and Muro, though, make the right decisions throughout, elevating scenes with atmospheric lighting and increasing intensity with well-chosen angles and shots.

Author Bio: Chad Durham is co-editor and contributing writer for RogueAuteurs.com. He also participates bi-monthly in the Rogue Auteurs podcast. His day job is high school English teacher. He has been in love with movies since seeing The Sting when he was 12. The thrill and emotion of seeing a great movie for the first time will always be one of his favorite feelings.