Roman Polanski’s 1968 film Rosemary’s Baby is a product of a time of not only social upheaval in the United States, but one of massive artistic upheaval as well.

Based on the 1967 novel of the same name by Ira Levin, the film came about during a time when American cinema was undergoing a period of modernization marked by a subversion of traditional genre films. This marriage of innovative and traditional thriller film traits has made Rosemary’s Baby the ideal example of a film of the thriller genre. The matchlessness of the film manifests itself in the following ways:

1. The Inversion of Nature and Security

Part of the thematic brilliance of Rosemary’s Baby is its success in playing off of one’s natural trust in things like doctors, urban living, loved ones, and the elderly. One assumes that Dr. Saperstein must have good intentions given his profession, no matter how bizarre his methods may be.

Furthermore, Roman and Minnie Castevet, the Woodhouse’s elderly and eccentric neighbours, are the ideal antagonists based on the stereotype that they are no more than a harmless, nosy old couple. Most importantly, the film’s treatment of pregnancy as a representation of danger and ambiguity is a prime example of the film’s perversion of something innocent and above all, natural.

One particular example of this form of inversion in Rosemary’s Baby is the use of setting, and the brilliance of portraying a quaint urban apartment as a malevolent location. A departure from the archetypal haunted Victorian mansion of old, the idea of the modern, inner-city apartment as a place of menace is a concept previously explored by Polanski in Repulsion (1965), and would be expanded upon in The Tenant (1976).

However, many classic ‘haunted mansion’ tropes are incorporated into this contemporary setting: The Bramford building contains not only an eerie basement with a dark history, but hidden passageways as well that evoke some sort of Castle Dracula in the middle of New York City. Such a choice plays not only upon the perceived security of the home, but also upon that of the modernity and comfort of apartment living and how removed it is from such archaic superstition.

2. The Score

The scoring of Rosemary’s Baby is commendable in that it accomplishes the goal of complimenting or setting the tone of the film without fail. As early as the opening credits, which features a lullaby sung by Mia Farrow to musical accompaniment, we are treated to a preview of the film’s tone. The lullaby, though soft and innocent on the surface, is backed by shrill and devious tones lurking beneath—foreshadowing the menace that lies beneath the surface of the story.

The music of the film also goes on to perfectly punctuate the moments of dread and hysteria as the plot advances, while also capturing the supposed banality and innocence of living in the Bramford.

One is transported from warm melodies highlighting the whimsy of decorating a new home or the holiday season in New York City, to subtle piano white noise (muffled ascending and descending scales, as well as Für Elise played ad nauseam from some unknown origin), and ultimately to frantic, anxious horns as the danger escalates and reveals itself.

3. The Pace

One creative choice that separates Rosemary’s Baby from contemporary thrillers is its pacing. Many modern thrillers fall victim to the shortcoming of rushing through the plot and not properly building up to their reveals. In the case of Rosemary’s Baby, exposition and revelations are unveiled slowly over time, and the plot is allowed to come to light at a steady pace; culminating in a well-deserved payoff in the conclusion.

An ideal example of this patient pace is the ‘Scrabble’ scene, where not only does Rosemary not immediately solve the ‘name is an anagram’ advice of her deceased friend Hutch, it takes multiple attempts and allows the mood to build through the entire scene until the chilling discovery.

Another way the film paces itself is by leaving seemingly-innocent hints early in the film before any trace of evil emerges in the story. For example: Rosemary’s observation to Guy that the Castevet’s had seemed to have taken all their pictures down before having them over for dinner. It isn’t until the closing of the film that it’s revealed that the Castevet’s art collection consists of disturbing satanic imagery.

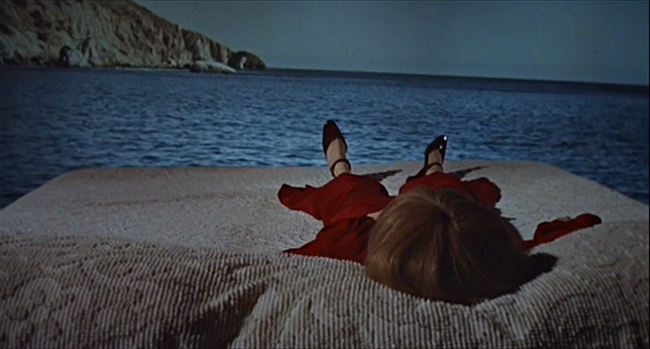

The result of this consistent patience and attention to detail results is an overall richness of the film. It would have sufficed for Rosemary’s drug-fuelled dream sequence to only consist of the infamous rape scene, but it is instead drawn out into a surreal experience that incorporates Bramford staff as well as Catholic influences and seemingly random vignettes—culminating in one of the most daring and memorable segments of the film, as well as one of the most endearing representations of dreaming in cinema.

4. Metaphor

There are multiple metaphors to be found within Rosemary’s Baby, the most prominent of which is the manipulability and victimization of women in the 1960s. Even during this era of second-wave feminism the film presents American women as easily taken advantage of through the abuse of power by male authority figures—including her husband, Guy, who nonchalantly plays off allegedly raping Rosemary in her sleep, and is all too quickly forgiven.

Rosemary’s attempts to protect her unborn child from the coven can be interpreted as a woman taking reproductive matters into her own hands any defying an oppressive system. In one scene she comforts her unborn baby: “Don’t you worry, Andy-or-Jenny, I’ll kill them before I let them touch you.”

A more heavy-handed interpretation of Rosemary’s Baby is the perceived increase of secularization and godlessness of the era. A theme touched on throughout the film, one first sees the question of the death of god in society with the Castevet’s light mockery of the Pope, along with Rosemary’s feelings of lapsed-Catholic guilt throughout.

Later on, after convincing herself of the plot carried out by witches living in the Bramford to sacrifice her unborn baby, Rosemary comes across the April 8th, 1966 edition of Time Magazine with the unsettling blood-red cover title “Is God Dead?”—a question echoed and affirmed as a victorious declaration by Roman Castevet in the film’s climax.

5. Ambiguity

The ambiguity of Rosemary’s Baby—that is to say the very real possibility that the conspiracy and evil that threatens Rosemary is all in her mind—is a crucial factor in defining the film as a thriller rather than simply a horror film.

At one point she confides over the phone to Dr. Hill “you’re probably thinking ‘my God this poor girl has really flipped’”. This exchange illustrates that Rosemary is very aware of how outlandish her assertions sound, to the point where the audience begins to question the validity of her paranoia as well.

6. The Twist Ending

Although seen in the present era as cliché, a major factor in the longevity of Rosemary’s Baby is the immortal twist ending. This scene could be described as an amalgamation of everything that makes Rosemary’s Baby exemplary. The scene builds up to a provoking ‘anti-reveal’ wherein the sight of the baby that so horrifies Rosemary is hidden from the audience.

This forces the audience to craft their own visions of the infant and its father’s demonic eyes—of which each of our own fantasies would be undoubtedly more frightening than anything 1960s-era visual effects could conjure. This scene is complimented masterfully by the shrill, unsettling horn solo that crescendos from silence with the borderline cartoonish widening of Rosemary’s eyes at her discovery.

7. The Unresolved Conclusion

One of the reasons Polanski’s later film Chinatown (1974) is so universally hailed for its screenplay is due to the unresolved ending. Rosemary’s Baby is undoubtedly an earlier example of this tried and true method. The effect achieved by ending a film on such a conclusion devoid of closure and resolution is that such an ending stays with the audience and leaves a profound impact on their memory of the overall viewing experience.

Rosemary’s initially reluctant surrender to the coven’s scheme to have her raise Adrian is a sort of coup de grâce; a fatal blow of the psychological assault waged by the film. The audience is confronted with the truth that not only is the conclusion even worse than one would imagine, it only gets darker. The menace that haunted Rosemary is not only quite real, but it prevails in the end.

Author Bio: Sam Fraser is a literature-turned-film student at Université de Montréal. He still operates under the illusion that he might one day run into Denis Villeneuve or Xavier Dolan on the métro.