Luc Besson has undoubtedly been influential with his production company, EuropaCorp, which has had an almost incalculable global impact, particularly on the action genre with iconic franchises like Taken and Transporter. Many of EuropaCorp’s action films are also written by Besson.

Of course he’s also directed a number of films himself for his production company, and now three years after the huge success of his 2014 SF thriller Lucy, he is on the verge of releasing what promises to be one of this summer’s most spectacular blockbuster popcorn movies, Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets.

Way back before the founding of EuropaCorp in 2000, however, Besson wrote and directed several films that formed the foundation of his unique cinematic sensibility, which combines explosive and sometimes brutal action with a disarmingly humanistic, sentimental and even whimsical sensibility.

Besson’s unique voice as a filmmaker—and the appeal of his films—is difficult to come to grips with, and his films routinely fare much better with audiences than they do with critics. In this list we’ll look at Besson’s first eight films and consider how his style is defined by them, while ranking them from worst to best. In their own ways each one is singularly fascinating and guaranteed to entertain.

8. Atlantis (1991)

A lovely and very different kind of undersea nature documentary shot in locations around the world (as detailed in the final sequence before the end credits). Atlantis differentiates itself from other nature documentaries in that it mostly steers clear of narrativizing and anthropomorphizing the activities of the undersea creatures and landscapes that it depicts.

The opening voice over preamble—the only narration in the entire film—simply invites viewers to step away from the noise of their daily lives and enter a different world.

The remainder of the film makes good on that introduction to form a kind of a concept album of music videos with a synthesizer and orchestral score by Eric Serra.

There are a dozen more or less precisely separated sections (La Lumiere/The Light, La Nuit/The Night, etc.) that each focus on either a type of undersea creature (dolphins, an octopus, etc.) or formations in the aquatic landscape (coral reefs, ice floes, etc.). It’s particularly noteworthy that until the very end the camera does not rise above the water’s surface even a single time, which serves the simple film’s goals subtly and well.

Thanks to the beautiful camera work that, for the most part, simply tracks through the various underwater environments, and a score that is as lighthearted as it is adept, Atlantis makes for a pleasant hour and a quarter. It’s worth seeing, but not worth going too far out of one’s way to do so.

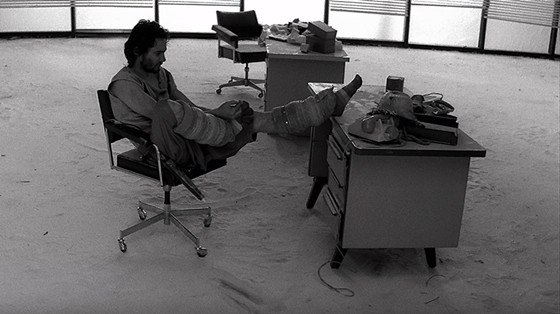

7. Le Dernier Combat/The Last Battle (1983)

With its post apocalyptic desert setting, Le Dernier Combat feels loosely, distantly inspired by earlier films like A Boy and his Dog (1975) and Mad Max (1979). Because those films had the benefit of having characters who could speak (including even the titular dog in the earlier film), they also were able to more readily pass expository information to the viewer and explain the basic circumstances of their settings.

Le Dernier Combat cleverly avoids such explanations, instead simply immersing us in its world where people have inexplicably been rendered voiceless. The weather provides life-giving fish for food and life-destroying rubble falling from the sky motivated by nothing other than the needs of the plot.

Thus even in his first feature, Besson emerges with his narrative rule-breaking sensibility already almost fully formed, if not especially refined. He’s going to do it his way whether you like it or not, and he takes clear pleasure in plot points that transpire almost at random, simply because they move the story in the direction he wants it to go.

His quirky humanism is also on full display here as, for example, the only two characters who succeed in forging a friendship in this harsh environment are also the only to speak. With the aid of some sort of gas they manage to croak just one word–“bonjour”– to each other, much to their joyful amazement.

At its heart, Le Dernier Combat sets the tone for much of Besson’s early work. It ultimately focuses on the male protagonist trying to strike up a relationship with a female counterpart in its post apocalyptic world otherwise populated almost entirely by men, most of whom are bad men to a more or less murderously violent degree.

6. The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (1999)

Besson’s eighth directorial effort, his last before taking a break for several years, unfortunately sags under the weight of its legendary historical basis. In the early 15th Century Joan (Milla Jovovich), though of low birth, believes that God Himself has chosen her to lead France to victory against England’s invading armies, and at the tender age of 18 she does precisely that.

Unfortunately, however (at least in this somewhat controversial retelling of the story), her inability to come to terms with and fully embrace her own power (she instead persists in attributing her victory to Divine Grace) results in her conviction of heresy, the punishment for which was death at the hands of her English captors.

This humanization of his sainted protagonist is Besson’s greatest departure from accepted lore, and it is firmly in keeping with his strong focus on the core humanity of the characters in his films.

There have been other filmed versions of the story of Saint Joan, most notably Carl Theodor Dreyer’s grim and weighty 1928 silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc, one of the great classics of early cinema. For better or worse, any subsequent retelling of the story has quite a distance to travel in order to emerge from the long shadow cast by Dreyer’s stunning film which focuses entirely on Joan’s trial and execution.

Besson attempts to give this shadow the slip by focusing first on Joan’s early life leading to her experience of divine revelation, and after that focusing on the battlefield action elements of the story on the one hand, and subjective point of view sequences of Joan’s spiritual hallucinations on the other.

It’s all undeniably and often spectacularly entertaining, but it also persistently circles back to a place where it somehow doesn’t sit right to be so entertained by something with such grave historical magnitude.

5. The Big Blue (1988)

Besson was born to parents who were scuba diving instructors, and he spent his childhood traveling the world with them from sea to sea. Their work, their divorce, and his own diving accident that for a time prevented Besson from being able to dive are all writ large in the heavy emotional drama of The Big Blue that revolves around the quirky and conflicted polygonal relationship between champion deep sea diving rivals Jacques (Jean-Marc Barre) and Enzo (Jean Reno), Jacques’ love interest Joanna (Rosanna Arquette), and the sublime and mysterious ocean depths themselves (which also form a kind of alternate love interest for Jacques).

Thankfully the long (nearly three hour) version of this film has, in the age of video, pretty well entirely crowded out of existence the much shorter original American theatrical release version (which was a box office flop in strong contrast to the film’s huge success in international distribution). Not only did the American theatrical version suffer incalculable damage from being re-edited to speed up its pace, it further lacked the indispensable Eric Serra score originally created for it.

Some things move better when they more more slowly, and The Big Blue is a powerful, even magical example. Besson’s love of the undersea world—rendered so clearly in Atlantis—winningly combines here with the indefatigably joyful attitude toward humanity that mixes the serious and the silly as only he can do.