Part of the the charm of watching a foreign movie heavily resides in viewing–and relating to–the unique interpretation of filmmaking that varies from culture to culture and country to country.

Whether it’s the heavy stoicism and existential dread of Northern and Eastern European dramas, the light farce produced by French directors, or the upbeat fantasy provided by Bollywood, foreign films can be illuminating windows into the subtleties of various cultures around the world. For some filmgoers, it’s the most variety of culture they can engage with besides reading books and watching travelogues.

But those subtitles! In dialogue-heavy movies especially, having to keep up with the action on-screen while also reading the small, white (or sometimes, to great annoyance, yellow) subtitles on the bottom of the screen is distracting, if not ruining the experience of watching the film as a whole.

Many film fans have been turned off of watching foreign imports for this very reason. This is unfortunate, considering how many great films have been made–and continue to be produced–outside of English-speaking cultures. However, for a glimpse of cinema from around the world without all of the reading involved, here are eight great foreign films with little dialogue–and even fewer subtitles–that can be enjoyed without having to glimpse down at a block of text every few moments.

1. Alice

In 1988, Czech filmmaker Jan Švankmajer adapted Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as a dream-like (some would say nightmarish) stop-motion, mixed with live-action, feature film. Perhaps the most unique interpretation of the story, Alice accentuates the darker aspects of the story wherein a young girl is transported into a strange and hostile fantasy land.

Rather than depend on the social satire of Carroll’s original story, Švankmajer simply depicts the events of the story as-is, presented more as a reflection of Alice’s subconscious creating the story rather than the plot being dependent on Carroll’s allegorical meaning. The result is visually striking with the handmade charm of somebody who has a very specific, unique vision.

While there is heavy narration throughout (provided by Alice), anyone familiar with the Alice In Wonderland story can make due without having to read it. Outside of these narrative intervals, much of the film plays like a silent film, featuring the somewhat grotesque stop-motion figures of the familiar White Rabbit, Caterpillar, and Mad Hatter and Hare playing out the traditional beats of the story.

Stylized and wildly innovative, it provides a stark contrast to the more recent CGI-infused retellings of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which have enjoyed budgets 100 times higher than this Alice, but are still nowhere near as impactful or impressive as this adaptation.

2. Themroc

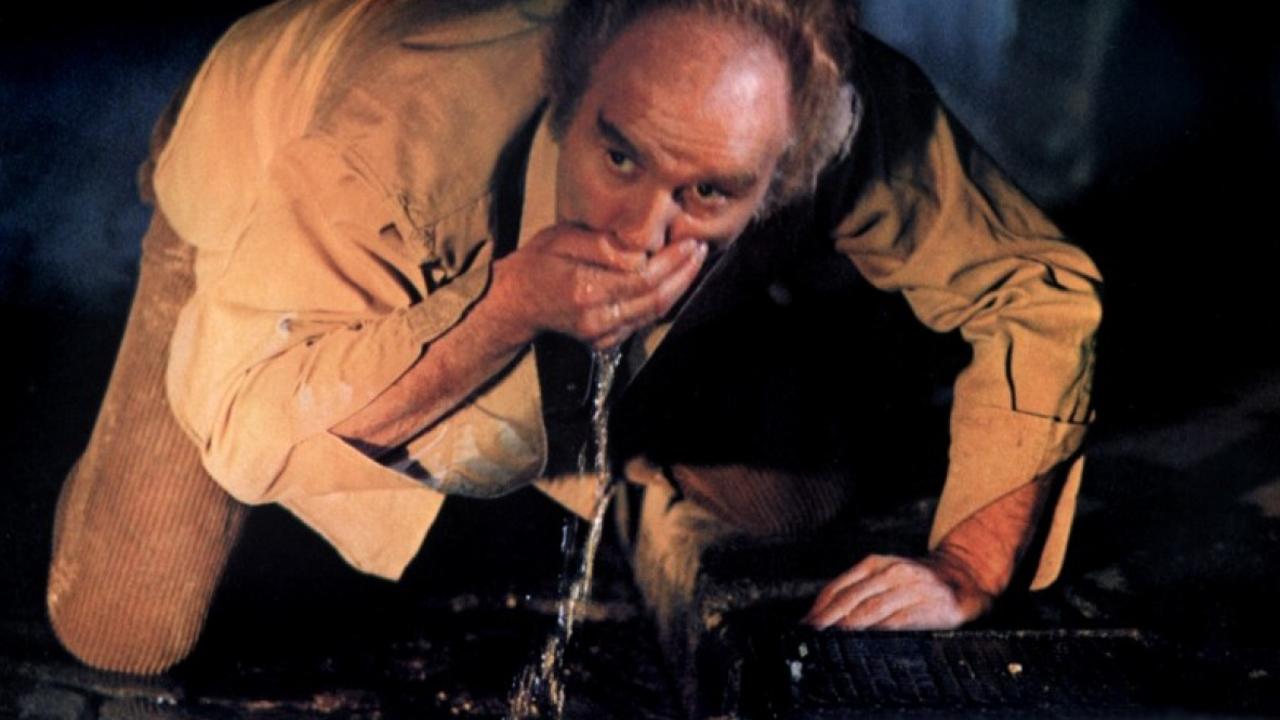

Think of Altered States minus the drugs that gets to where it’s going much quicker, and then goes way too far, and that’s Themroc for you. A working-class man suddenly snaps and rebels against modern society by descending into a primitive state as he turns into a cityscape neanderthal.

Conditions deteriorate quickly as he quits his job, devolves into a primitive state by screaming at train cars, goes home to have sex with his surprisingly willing sister, and then adopts the neanderthal lifestyle. The apartment becomes a modern caveman habitat as he smashes out the window and walls of his domain, throws out of this new chasm in his third-floor walkup all modern items, and lives a primitive lifestyle while we witness a regression of a modern-day man into an earlier form of himself.

Artful in its quirky, anthropological look at human behavior (both civilized and not), Themroc is a larger on the more unvarnished and primal notions of human psychology. Conflictingly a conforming species, an ego-driven sort, and also a lustful and violent one, the delicate balance between the shared normalcy of civilization and the brute animality of human nature are compared and contrasted in this film.

Of course, this would be a product of the symbolism-heavy film output of France. Featuring unintelligible dialogue both pre- and post-regression, this unique film captures a bizarre look at a (somewhat) civilized, modern man as he abandons all pretense of this so-called civility. It continues its surreal pacing throughout as the worker’s caveman lifestyle starts to spread through the neighborhood, and many more begin to follow the idea of breaking down the walls of modern artifice to lead a much simpler life.

Both symbolic and primal, Thomrac deals with the animal side of human beings and forces its viewers to see it as both an anthropological survey and weird farce. An exploration of societal norms and a subversion of such pretensions, this film explores the raw, unconscious desires that inspire our worst and best impulses and behaviors and suggests that civilization is just a sheer veneer applied onto humanity that is only held together by mutually agreed-upon rules. Otherwise, we may be be the same barbaric, confrontational figures depicted throughout Themroc.

Potentially viewed as a romantic hangover from the turbulent May ‘68 events in France (scenes featuring the police are best framed with this this notion in mind), its revolutionary spirit–and wildly transgressive film spirit–set this film as a protest piece of sorts.

Of course, you’d have to know French revolutionary history of the 1960’s to maybe read into this as such, but otherwise if you’re looking for wildly subversive foreign content besides French Extreme or Korean horror, this bit of surreal Freudian/Lynchian madness is a solid choice for viewing a strange (and wordless) transgressive drama better than most.

3. I Fidanzati (The Fiances)

The heartbreak of a long-distance love is familiar to anybody who’s been separated from their partner through either necessity or circumstance. In I Fidanzati (translated as The Fiances), a factory worker (Giovanni) in North Italy accepts a promotion from his employer to help start a new department in their far-away factory in Sicily for 18 months. This separates him from his fiance Liliana, and the film is an exploration of the strain and turmoil that their long-term, long-distance relationship undergoes.

While initially excited by his new surroundings and a change of pace from his staid, predictable relationship with Lilliana, he soon finds himself nostalgic for the familiarity and intimacy of their relationship. Experiencing the loneliness that being suddenly single naturally engenders, he rediscovers his feelings for her and starts to find his way back into her heart.

While this sounds like thin soup for the plot of a movie, the magic and humanity of I Fidanzati is carried through by the delicate touch of director Ermanno Olmi, whose humanistic treatment of his subjects allows the viewer to regard the protagonists’ heartaches and intrinsically conflicting desires as part of the everyday business of being alive and figuring out love.

There are no superheroes or wild action pieces in I Fidnanzati, just poetic Italian neorealism telling a small story of love between two regular people. Part of this poetry comes from how Olmi tells this story, largely through unspoken communication of gestures, facial expressions, and the physicality of the characters.

As much a love story as a look at the changing urban and economic conditions in Italy in their booming post-WWII economy, Olmi seems to suggest that while the world around us may change, reconfiguring and rebuilding itself over and over, the constancy of human emotions–of love, heartbreak, and hope–are the true foundations of life. At 77 minutes, I Fidanzati is a brief, memorable look at these universal feelings.

4. The Tribe

Only using Ukrainian sign language with no subtitles, The Tribe tells an unexpectedly dark tale of a mute young man who arrives at a school for the deaf. There, he is introduced to The Tribe, a gang run out of the school by its students, and he is quickly drawn into their sordid world of thievery and prostitution. When the young man falls in love with one of the young prostitutes–to whom he’s her new pimp–the stakes are raised and the film draws towards a tragic conclusion.

It’s a severe turn for a story taking place in a school for the deaf (considering that most filmgoers’ touchstone for the aurally handicapped is Children of a Lesser God), and these sordid details unfold as the viewer–whether fluent in sign language or not–is drawn into the mounting tragedy our alienated characters find themselves in.

With no dialogue and whose only sound is diegetic to the scene, The Tribe builds its tension in the absolute silence that encompasses its world, subjecting the audience to the sensory isolation that the deaf experience on a daily basis. Comprised of a sequence of long-action shots and a dispassionate eye that views savage violence and raw, sexual scenes with the same neutral measure, The Tribe is an affecting import that stays in the mind long after the final scene draws to a close. Both a portrait of the alienated and a raw look at young life subject to an indifferent reality, The Tribe is a silent movie that speaks volumes.