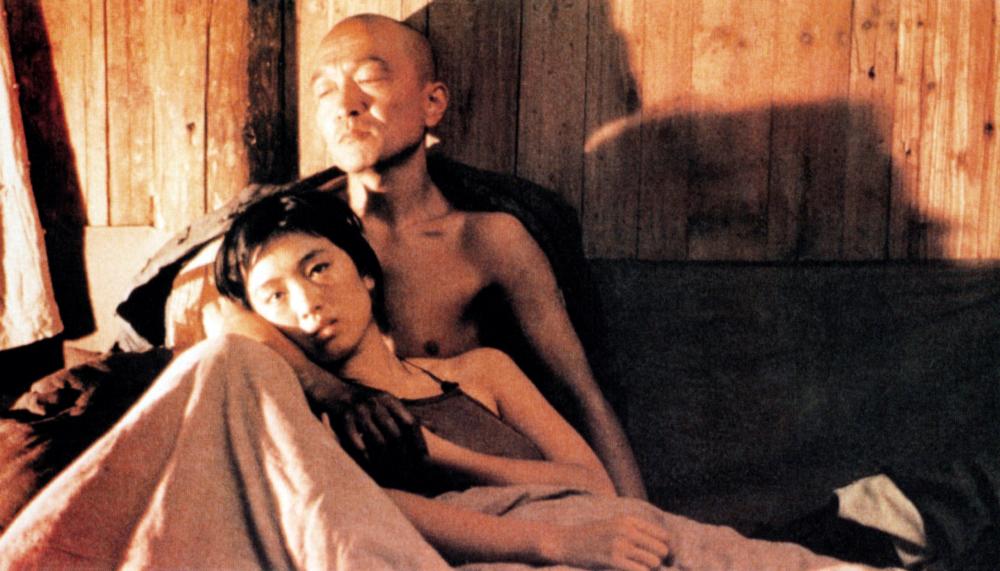

5. Cyclo

A poetic and intense look at life in poverty in Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam in the early 1990’s and the exacerbated situations and unfortunate circumstances that a family find themselves in when a pedicab (the titular cyclo) that the young, nameless man and his family depend upon is stolen.

The meditative gaze director Tran Anh Hung develops is a hypnotic, nodding rhythm akin to Gus Van Sant’s steady focus or City of God’s documentary-like feel, providing Cyclo a genuine authenticity as a look at a time, place, and the downtrodden’s life in Ho Chi Minh.

Particularly those barely eeking out existences on the street, barely surviving from day-to-day from backbreaking labor for low wages, such as the fate of our nameless cycler and his family–his beautiful sister (water carrier), younger sister (bootblack), and grandfather (bicycle tire repairman). When said pedicab is stolen, the young man is coerced by his employer (who owns the bike) into working for a criminal enterprise to pay back the debt with his new boss, a pimp who’s also a poet.

The movie falls into tragedy when his sister also begins working for the pimp as his prostitute. Watching these seemingly honorable characters being forced through inescapable circumstance stripped of their common dignity simply because they have no other choice if affecting and provides an often harrowing viewing experience. As events continue to escalate dramatically for this family and their increasingly desperate situations, both tragedy and a sense of acceptance of the defiling horrors of life culminate to often unpleasant resolutions.

Although firmly rooted in realism and a human scale, the film unfolds like a dream that turns into a nightmare, with much of the story told through its cinematography, sound design, and action on the screen; that is to say that there’s very minimal dialogue. It serves this story better without, anyway: only a film that gets so dark in its realism can only inflict so much on its audience until it becomes too much.

6. Ju Dou

Taking place in 1920’s rural China, Ju Dou is a tragedy of doomed love and the human-level repercussions of an oppressive society. A young woman (the titular Ju Dou) is sold as a wife to a cruel and elderly fabrics dyer, Jinshan, who abuses her out of frustration of his own impotence and inability to sire a child.

Ju Dou begins an affair with Jinshan’s nephew, Tianqing, and soon becomes pregnant with his child. Jinshan has a stroke and becomes paralyzed while Ju Dou pretends the child she is pregnant with is his. The affair is eventually discovered, and Jinshan attempts to kill the child in utero and tortures Tianqing. Time passes, and while Jinshan has accepted the boy as his son, he falls into a vat of dye and drowns.

More time passes and Ju Dou and Tianqing run the dye operation; the young boy has grown into an angry teenager who is haunted by rumors in town of his parents’ affair. The story descends into a violent, tragic ending while the audience is left contemplating the symbolic meaning behind the story and how tradition and social mores can destroy otherwise innocent lives.

Although the plot itself is heavy lifting, what makes this film such a treat is its visual beauty with its artful, detailed mise-en-scene shot in three-strip Technicolor. The film visually elucidates a far-away time and place in China, richly providing a window into history while underscoring the drama at play onscreen. And, like all of the films on this list, its dialogue is minimal, which means this is a subtitle-light foreign film to enjoy.

Ju Dou was the first Chinese film nominated for Best Foreign Film in 1990 and was briefly banned in China, its country of production, for its frank depiction of sexuality and subversive commentary on the older generation that run the country. Upon release, it gained worldwide popularity on the arthouse circuit and was eventually unbanned in its home country.

7. Solaris

This sci-fi film from Russia during the Cold War is considered one of the greatest of its genre. A psychologist accepts a mission to the Solaris Station, which orbits the fictional planet Solaris, to make sure everyone’s doing OK up there. It turns out they’re not, as a scientist has killed himself and the remaining two crew members are seemingly traumatized. Other figures begin to appear, such as the psychologist’s late wife, Hari, who appears to him. The first time she does, he lures her into a space pod and blasts her off of the station.

But she reappears again, and when he traps her, she injures herself severely trying to claw her way out of the room.When he finally relents to aid her, her wounds heal instantly. The surviving Solaris members have a meeting and after introductions are made to Hari, they launch into the explanation: apparently there’s a living being from the planet Solaris which has been trying to make contact with the members of the ship. However, after finding nuclear testing aboard, the Solaris visitor (some sort of invisible, sentient, collective being) has grown hostile towards them.

What follows is a sort of Russian 2001. The film and its characters launch into an intimate, but universal, look at the metaphysics of love, the nature of reality, the existence of other forms of beings in the universe, and other highfalutin concepts. It’s also a beautiful film of its genre whose aesthetics still hold up today, and the story is infused with the sort of mournful philosophy that traditionally colors Russian fiction. Best of all, it’s a top-shelf, classic, and artistic sci-fi film that won’t wear your eyes out with heavy dialogue blocks that you have to strain to read.

8. Play Time

Jacques Tati was a master of physical comedy, a sort of French Charlie Chaplin. Although he only completed a handful of films in his lifetime, some have become classics of French comedy, including his humorous look at life in small, rural French town (Jour de Fete, or The Big Day), and the classics Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Oncle, which both star his signature protagonist, the hapless Monsieur Hulot.

With his background in pantomime, most of Tati’s work is subtitle-light and utterly charming, but perhaps his masterpiece is the sprawling and visually complex Play Time. Filmed over three years on enormous sets that replicate a cityscape, the story (as much as there is one) follows several characters over the course of a day as they navigate an ultra-modern version of Paris, often facing farcical situations due to the supposed advancements in technology for convenience.

Upon its release, it was at the time the most expensive French film in history, and although a critical success, it spelled financial disaster for Tati. The film is unlike any other and had been aptly described as a movie that an alien would make about human beings by Francois Trauffaut and Thom Yorke. The sheer scope of Tati’s vision–including building an entire functional glass-and-steel city as its set–is impressive, and works like a live-action Where’s Waldo? film, with each frame frilled with small details, characters, and behaviors that are difficult to pick up on in just one viewing.

As with most Tati films, dialogue is not important here, but what he’s commenting upon is: largely a skeptical view at the increasingly technology-obsessed society that was covering up the heritage and charm of Paris, Tati’s characters busily run around the whiz-bang maze of modern life and only pause in relief when a glimpse of that old world surfaces, however briefly.

Author Bio: Mike Gray is a writer, editor, and academic from the Jersey Shore. His work has been featured on Cracked and Funny or Die, and he maintains a humor recap film blog at mikegraymikegray.wordpress.com.