We must speak about institutionalization, what this really means and what is lost in the process. Perhaps we should first look at the most memorable institutionalized figure of cinema: Brooks Hatlen, a character from “The Shawshank Redemption”.

When he finally gained his freedom after spending most of his life in prison, he would carve his name on the wall, just like the bored inmates in his former prison would do, before he hangs himself. His character is a warning to one of the film’s main characters, Red, who after being released during the end of the film, wonders if he will be able to adapt or will become just as lost as Brooks.

The normalcy of the outside world is frightening, inside everything is simpler. All of this freedom outside becomes too much and it’s inside these confined walls, where they sometimes have to give up their youth or their finest years, where they need to make a home.

During the years spent in a penal institution, under the mercy of guards and gangs, in a culture of violence, the human animal must adapt like any other animal in the wild. It seems harrowing to us, but it becomes their home. It becomes all they know. It will shape them. They become who they are because of it.

I believe it’s Michael Mann’s understanding of prisoners, during his extensive research while doing a rewrite for ”Straight Time”, that marks much of his work. His budding friendship with Edward Bunker – who wrote the novel upon which “Straight Time” was based – signified this as well. Much of Mann’s work would have people either institutionalized or marked forever by their experience of the penal system, beginning with his debut “Jericho Mile”, where a lifer can only seem to escape the confines of the prison walls by running record lapses.

This would be followed up by “Thief”, where the main character fears prison like a strict Catholic would fear the damnation of hell. This is even more signified through his relationship with his mentor, whose soul has become broken by the endless years spend in prison. In “Heat”, the fallen criminal Neil would tell the cop who kills him, ‘’I told you I’m not going back.’’

There would come more examples of this but even his cast of characters who never did time are locked in their own kind of prison. This prison can be different things; it’s just not a psychical institution, sometimes it’s as basic as the frailty of the human mind. In “Collateral”, the prison is dreaming, the constant dreamer who never makes the definitive step to follow through on his dream.

In “Manhunter”, an FBI profiler, in order to understand the psychopathic mind, becomes to fear his connection to the monsters he’s hunting down. The prison in “Manhunter” is empathy. And likewise, the monster of “Manhunter” is a prisoner of his own psychopathic void; no matter how hard he tries, he can’t escape his nature. In “The Keep”, a Nazi officer constantly struggles with his conscience and his allegiance to his army code. In Mann’s biopic “Ali”, the prison is legacy, living up to your legend, one’s own hubris. Being imprisoned can be spiritual, misguided loyalty, the lies we tell ourselves.

In most of Mann’s films there are the quiet moments; the main character gazes out the window, and perhaps in that moment, there’s the fleeting awareness that they are trapped somehow. We don’t see these moments in other people, we don’t know what’s going on in the mind of a stranger sitting by you on the subway. Perhaps they are trying to find a way out, and perhaps they will find it, but many won’t. Just like in Mann’s films, for many of them it becomes too late. Death becomes the only way to escape yourself.

Aside from the technical artistry of Mann’s films, it’s this theme of imprisonment, the oppression of the human soul by internal and external factors that make these films feel so intimate. Mann has not always hit a home run, but there can be doubt that from reviewing the glory of his filmography, that he’s one of the greatest working today.

13. L.A. Takedown

It’s hard to judge this film on its own right, knowing that its eventual remake, “Heat”, is superior on every front. It would be like comparing a well-made TV version of Mario Puzo’s “The Godfather” to Francis Ford Coppola’s classic adaptation. Once you see Marlon Brando stroking the cat, you’ll forget all about the TV film. It’s just not fair.

“L.A. Takedown” was initially a pilot for a TV series that never got made and was then subsequently released as a TV movie. While the action scenes of “L.A. Takedown” are certainly commendable, it’s completely overshadowed by “Heat”, which has one of the most memorable shootouts in cinema history. Is it even worth mentioning that “Heat” has the more legendary cast? Sure, Scott Plank and Alex McArthur are fine leads, but in “Heat” we have two legendary actors standing off: Al Pacino and Robert De Niro. We have a worthwhile supporting cast with “L.A. Takedown”, but it’s laughable compared to “Heat”.

The plot follows “Heat” along the same lines, but it’s much shorter, clocking at 97 minutes compared to the remake’s two hours and 50 minute runtime. Perhaps it’s a more focused film, focusing solely on the central main characters, but these characters aren’t as well-defined nor iconic as the “Heat” counterpart. It was also precisely the subplots in “Heat” that made it stand above its fellow genre pieces. It made it an epic, the supporting characters were all defined, and it gave humanity to characters who would usually be stereotypes. It created a believable universe on its own.

“L.A. Takedown” is a solid ride from start to finish, but as Mann has said himself, it’s a merely a blueprint for what would become his ultimate masterpiece.

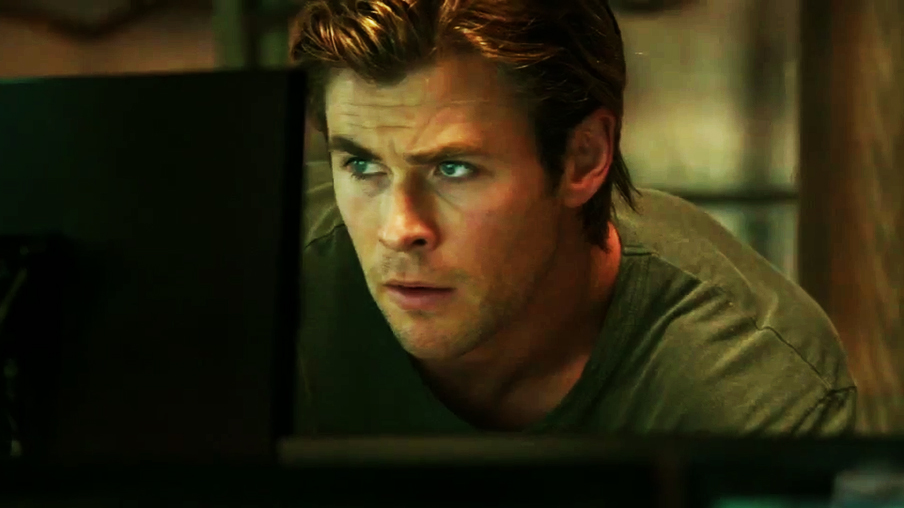

12. Blackhat

Cyber-terrorism is one terrifying menace that most of us don’t even want to dare contemplate. The general public isn’t too worried about it but the security agencies know that tomorrow’s terror attacks may come from somebody’s home computer.

In many respects it’s understandable why the subject of cyber-terrorism is ignored. The internet is such an inescapable part of our lives now. We get our (fake) news from the internet. We do business through the internet. Who wants to go across the street when we can just order things online? We transfer money through the internet. We share intimate parts of our lives through the internet. People find true love thanks to the internet.

The idea that all of this could be in jeopardy means the end of the world for most of us. But it can happen. Bank accounts can be emptied by hackers. Blackmail fodder can be accessed through personal accounts. Government secrets can be encrypted. Buttons can be controlled through the other side of the world, buttons that can release hell on earth.

This is the world we live in. We can’t stop the machine. It’s happening and we can’t escape it. We don’t want it to. We are so enamored by our gadgets, the constant distractions available to us. There’s so much juicy content: breaking news, a surprise trailer from this movie you’ve been looking forward to, another outrageous tweet by some maniacal head of state.

The subject of cyber-terrorism for a movie is enticing enough, were it not for the many embarrassing attempts at portraying the act of hacking (anybody remember “Hackers”?). But this is a Michael Mann film. It might not portray hacking in its most realistic form, but with Mann at the directing helm, it will have a higher semblance of respectability. Much of the praise for “Blackhat” came from hackers themselves who concluded that this might be the most realistic portrayal.

Unfortunately, “Blackhat” features all the problems of many of Mann’s films: a beautiful stylistic picture with dreadfully boring leads. To say that it’s style over content does not do it justice. There is content here, it’s just the human element that’s lacking.

Based on a real-life event where a computer worm nearly destroyed a nuclear facility by the name of Stuxnet, “Blackhat” starts with a similar cyber-attack on a nuclear facility. Through dense CGI we get to see the inside of computers. A coolant explodes and people die. Soon enough, a trade-exchange gets hacked, pushing the price of soy upward.

The Chinese government and the FBI work together to find the perpetrator. When they realize that the hack code had been co-designed by its lead Chinese investigator Captain Dawai (Leehom Wang), they recruit his fellow designer, a current inmate serving prison time by the name of Hathaway (Chris Hemsworth) to aid them on this case.

Like most Mann films, the action is superb. When the shootouts start, its invigorating, exciting, the bullets are loud, it has an air of authenticity. Sadly, Mann has learned nothing from the failures of “Miami Vice”, since “Blackhat” has a love story between Hathaway and Dawai’s sister (Tang Wei) that’s nearly duller than the one central in “Miami Vice”.

These scenes slow the film down. You don’t really get to care about any of the characters, whether it Hathaway, Captain Dawai or stone-faced Viola Davis as FBI special agent Carol Barrett. The film only picks up at the action scenes and while there’s much to enjoy from Mann’s lovely digital cinematography, you just wish he would have engaging characters to go along with it.

11. The Keep

April 1941. The Nazi’s are at the height of their hubris. A platoon of Nazi soldiers, under the command of Capt. Klaus Woermann (Jurgen Prochnow), traverse occupied Romania, finding refuge in a mysterious citadel known as the Keep. When in the dead of night a few soldiers break open a wall to find silver, they release an evil force known as Radu Molasar (Michael Carter) who murders them and several Nazis the following days.

When Woermann requests a transfer, the higher-ups instead send a ruthless SD commander by the name of Eric Kaempffer (Gabriel Byrne) to find out what’s been killing the soldiers. They even become so desperate that they enlist the help of an ailing Jewish historian professor named Theodore Cuza (Ian McKellen) to translate the mysterious markings found in the temple. Meanwhile, a mysterious stranger named Glaeken (Scott Glenn) arrives who just might have the key to defeat this evil.

If you’ve never heard of this film and had this plot described to you, you would never guess that it was a Michael Mann film. But it was, and despite the different subject matter, many of his hallmarks are there: it’s beautifully stunning, there’s a love story, it’s scored by Tangerine Dream, it has a dreamlike feel to it. It’s far removed from the realism that he’s known for, but his voice is in there.

“The Keep” has become one of those fascinating failures from a prolific director; there’s so much greatness in there, but it’s bogged down by external forces. Even without doing any research on it, one could easily perceive its decisive failure: too much was cut down to do justice to the vision of the director.

The studio had zero faith in this film due to the many problems surrounding its creation (including the unfortunate death of visual effects supervisor Wally Veevers, which explains many of the shoddy effects) and the deplorable test screenings.

The original cut was 210 minutes long, which was then cut down to two hours only for the studio to cut it further to 90 minutes. The film suffers heavily from these edits. The best example of this, is the hilariously undeveloped love story between Glaeken and Eva Cuza (Alberta Watson); they meet and within minutes they are sleeping with each other. If you thought Mann’s later romantic subplots were bad, wait till you see this. Several subplots that would expand on its mythology and on its rich characters which were omitted, even the happy ending – you would think the studio loves a happy ending!

Even with this butchered cut – which is hard to find because it hasn’t even been released on DVD or Blu-ray – there’s much to enjoy from this film. It’s a visual atmospheric treat accompanied by a haunting soundtrack by Tangerine Dream. The actors, even with limited development, do a splendid job, most notably Jurgen Prochnow as a Nazi officer with a conscience, who also gets the film’s best dialog. Since other characters suffer from the studio’s brutal editing, only his character manages to come out unscathed.

Over time this film has received a cult following, despite it being disowned by Mann himself. Here’s hoping that one day the original cut will surface. It will certainly not be perfect, but it would be too intriguing to pass down. It’s a fascinating, beautiful mess that you won’t soon forget.

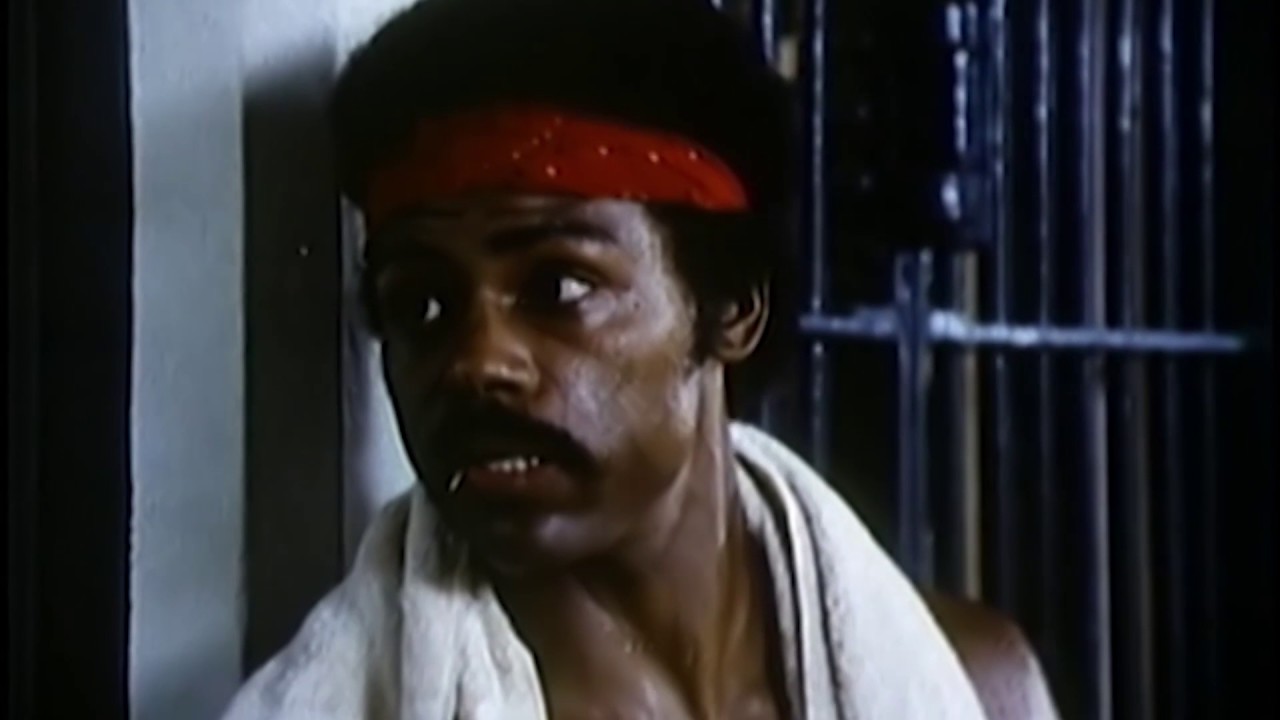

10. Jericho Mile

This is the film that made people pay attention to a burgeoning talent known as Michael Mann. He had previously done a rewrite for “Straight Time”, the underrated crime picture based on the legendary author/ex-con Edward Bunker, and in order to do the subject justice, Mann had spend rigorous research on prison life, even interviewing Bunker himself.

It’s apparent from the writing of this film that the research paid off because despite this being a TV film, it reeks of authenticity. The fact that the film was shot in an actual prison, Folsom, only confirms this. The stand-ins are mostly real prisoners, and the dialog is authentic to the times, though laughably jive. There would be numerous bouts of violence during the shoot, though the crew would never be afflicted or even bear witness to of these events.

The story is centered around a solitary prisoner, a lifer by the name of Larry Murphy (Peter Strauss) who likes to run around the prison yard. He doesn’t do his time in a normal fashion; he doesn’t read books, doesn’t watch TV, he just runs. He doesn’t have any regrets, he understands what he did and knows he needs to accept the adequate punishment for it.

When he runs long enough, he feels like he’s floating, he stops thinking too much. He feels this is the way best way to do time. When it is revealed that he’s actually breaking speed records, he gains the attention of the prison staff, who want him to participate in the Olympic trials. At first Murphy has no interest in this, but when a fellow inmate and friend gets murdered, he changes his mind and gains both new friends and enemies along the way.

The acting might not always be perfect; the low budget is apparent but if one is a fan of 1970’s cinema, this is a must see. It’s not polished, it’s not as hardcore as prison life would be depicted in the likes of “Oz”, but it’s got a got a heart and soul and authenticity that makes it essential watching for anyone interested in the prison genre. It’s filled with great character actors – Brian Dennehy, Ed Lauter, Geoffrey Lewis – and it’s the film that put Michael Mann on the map. His next film would become one of his masterpieces: “Thief”.

9. The Last of the Mohicans

It’s not easy ranking the films of Michael Mann, especially when you realize the surprising diversity of his filmography. When you watch “Collateral” and “Miami Vice”, you aren’t surprised this is by the same director. But then you realize he also directed “Ali”, “The Insider”, “The Keep” and the beautiful historical drama “The Last of the Mohicans”. This is as far removed from the gritty digital photographic world of “Blackhat” as you can get.

From the opening we are introduced into the lush wild world of the Adirondack Mountains in 1757 (it was actually filmed in North Carolina), where a tribe of Mohican Indians hunt down a deer. One of those Indians is played by Daniel Day-Lewis, and one can’t help but think of the tired outrage it would inspire if this would film would be made today. It is later revealed that he was adopted from a young age, but since we are in an age when people complain that Christopher Nolan’s “Dunkirk” didn’t have enough diversity, you can be sure that this film would spawn far more ridiculous condemnation.

The Mohican warriors (led by Russell Means) find themselves in the midst of the French-Indian War. Despite wanting to be neutral at first, they find themselves picking a side when they save a a high-ranking officer from the British army by the name of Major Heyward (Steve Waddington) and the two daughters of a highly esteemed colonel (Madeleine Stowe and Jodhi May). The French receive help from a rather brutal Huron chief by the name of Magua (Wes Studi) who has a personal vendetta against the Mohican tribe.

As is common in Michael Mann’s films, it’s the love story that is the least interesting. You know it’s going to happen and when it does, you’re just waiting for it to end. Perhaps Mann feels a love story is essential for the viewers to care – Cameron feels the same way – but often times it’s not really needed, especially when the relationship between other characters are much more interesting, such as the character of Chingachgook (Means) and his relationship with his two sons, as is Magua and his conversations with the French general (Patrice Chéreau). The final standoff between Chingachgook and Mague is just bloody fantastic – aided by the film’s incredibly moving score.

The historical accuracy has often been derided, but the original novel itself was guilty of this as well. It was even ridiculed by none other than Mark Twain for having numerous literary offenses. One should not take this film as a serious piece of history, but as more of a frontier adventure filled with great characters and in this respect, the films works perfectly.

8. Miami Vice

The last two decades saw an extraordinary rise of quality television and the question of what inspired it has become an endless debate. There is probably no clear cut answer. HBO certainly had a hand in it, starting with “Oz” and perfecting it with “The Sopranos”. But many would argue that it began in the 1980s, for instance, with “Miami Vice”, with its use of long story arcs and character development that would continue through the seasons. No more would the audience enjoy just an episodic show, they would – though still in its earlier stages – enjoy a drama that could come close to the complexity of a great novel.

Regardless of who deserves the credit for this, we know that Mann absolutely influenced what made “Miami Vice” work. He might have been just the executive producer, but the film’s iconic style and imagery – such as the lack of earth tones on the sets and costumes – is all thanks to Mann. He would later create the deeply underrated “Crime Story”, another gem that certainly gave a boost to the quality of television.

When it was announced that Mann would direct a big-budget cinematic adaptation of the show, there was certainly cause for excitement. The trailer cemented this excitement: the use of grainy digital imagery, coupled with exotic locations and the appropriate use of “Numb” by Jay-Z and Linkin Park made it seem like we were going to see something very special.

What we got was something special indeed, but certainly not perfect. There were problems on set – credited mostly to Jamie Foxx who after the success of “Collateral” discovered his inner diva nature – which caused the third act to be changed dramatically. But the film itself has problems, mostly due to the rather lackluster love story between Crockett and Isabella. The love story wasn’t as unbearable as we would see in “Blackhat” but it does slow the film down.

Ultimately despite its poor reception and mixed reviews, “Miami Vice” has aged gracefully. The digital camera use – especially in the action scenes – are one of a kind and if only the character drama was as interesting as the gunplay we would have had another Michael Mann masterpiece. It misses both the engaging character drama of “Heat” and the existential edge of “Collateral”, but when you rarely see such a big-budget crime drama with such an individual style, its mere existence is a blessing.