7. Public Enemies

The most frustrating films are not necessarily the really bad ones, but the ones that shine with greatness and just miss the mark of becoming a great film. “Public Enemies” is one such film. On the surface it seems to have everything: it looks great, the cast is great, the subject has so much promise and seems a perfect fit for a director like Michael Mann.

The life and death of John Dillinger has inspired many cinematic adaptations, yet none of them seem to do the subject justice. This film was supposed to change this. How could we expect differently? This is the story of one of the most famous criminals in American crime history and it’s told by Michael Mann, who notorious for creating the mother of all crime epics: “Heat”.

It’s hard to figure out what exactly went wrong here. This is certainly not a bad movie, it just isn’t as good as it should be. If you had to pick out one central problem with the film, it’s that you don’t find yourself emotionally invested in the characters. It feels like “Public Enemies” is a larger story, trimmed of all fat until it had an acceptable runtime.

It sort of feels like a season of “Boardwalk Empire” cut into a movie. These characters are fascinating but we don’t really get to know them. We are told who they are but we don’t get to see much beyond it. John Dillinger is “an outlaw who never thinks about tomorrow” – we are told this several times but we never really feel it.

It’s also hard not to compare this with “Heat”, seeing as it shares many similar story traits. We have a rivalry between a law enforcement official and a criminal, and there’s also a heartfelt romance that adds to the emotional core of the film. But we don’t really see a spiritual contrast between Melvin Purvis (a rather mundane Christian Bale) and John Dillinger (Johnny Depp, who does an excellent job) as we do with McCauley and Hanna.

Instead of the infamous ”barbecues and ballgames” monologue, the first verbal dialog between Purvis and Dillinger leaves you cold. The central romance between Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard) and Dillinger works well enough, but you wish Mann would devote more time to other characters, such as Red Hamilton (Jason Clarke), J. Edgar Hoover (Billy Crudup), Baby Face Nelson (an excellent Stephen Graham in a role that feels like a precursor to him honing the Al Capone role in “Boardwalk Empire”) and Charles Winstead (Stephen Lang, who nearly steals the film).

The only aspect that “Public Enemies” might be equally good in comparison are the shootouts, which are especially enhanced with the interesting use of digital cinematography – the contract of a digital look in a period setting was an inspired choice.

There’s so much to admire from this film and that’s why it’s so frustrating. This was supposed to become one of the great crime epics, but instead, it quickly fades from the mind. It also nags somewhat on the historical accuracy; at times it’s extremely accurate but the changes made are peculiar and don’t really add anything to the film. This while at the same time, other historical incidents and details are neglected, and many of them would have really been a value to the narrative.

There are moments when it reaches greatness – the emotional ending does deliver thanks to the sweeping music by Elliot Goldenthal – but deep down, you know it’s just not enough.

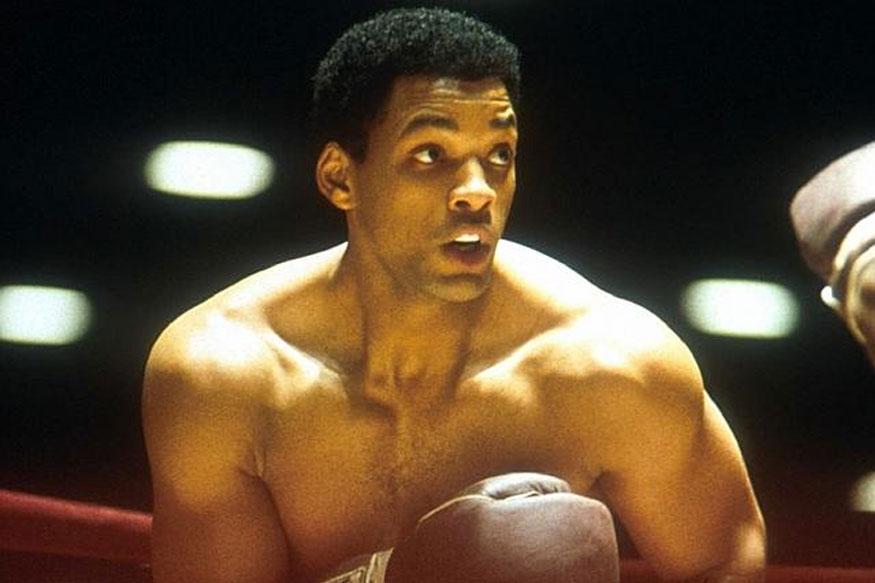

6. Ali

Like it or not, we will have a big-budget Donald Trump biography on the screen one day, that’s inevitable. It probably won’t be as fun as Alec Baldwin’s impersonation, but I can see Stephen Root doing a great job donning the infamous blond wig one day.

When it comes out, I suspect that it will receive similar criticism as Michael Mann’s “Ali” did: did we really need it? Like Trump, “Ali” was a first-class showboat, a man with not a trace of humility. He presented himself as the world’s greatest fighter, like Trump presents himself as the world’s greatest businessman.

While there’s more footage to be found of Trump, you can easily find enough footage of the great Champ himself: boasting and floundering, sweating and fighting, being knocked down and rising up again. So to answer the question: did we really need it? No, but we should be grateful that we got it.

Will Smith furiously studied for the part, even receiving The Great Champ’s blessing – apparently, Ali said Smith was the only one good looking enough for the part. He did everything one would do for that golden statue: he transformed his body, he altered his voice to perfectly fit his historical subject, nailed the mannerisms, and exuded the spirit of the great sportsman.

Even if you’re not a fan of Smith, for various logical reasons (mostly including his own massive ego and his obnoxious offspring), his performance is about as perfect as one could get. The rest of the historical figures seem all perfectly cast, from Jon Voight as Howard Cosell, Mario van Peebles as Malcolm X, Jamie Foxx as Dave Bundini Brown, to Mykelti Williamson as Don King.

The eponymous fights are recreated with obsessive detail, from Ali’s iconic footwork to the final combination punches that struck down George Foreman. There are bruises and blood pours down their sweaty faces. It’s a magnificent sport and it is portrayed brilliantly by Mann, but it does not shy from the madness of two men hurting each other for the sake of this sport.

The best thing of all is that it’s a balanced view of the great fighter. We see the legend but we see his incredible hubris in full display. We understand the political background of the times, his religious transformation, the corrupting effects that fame had on his character. It’s an incredible work of art and possibly one of the most underrated of Mann’s filmography.

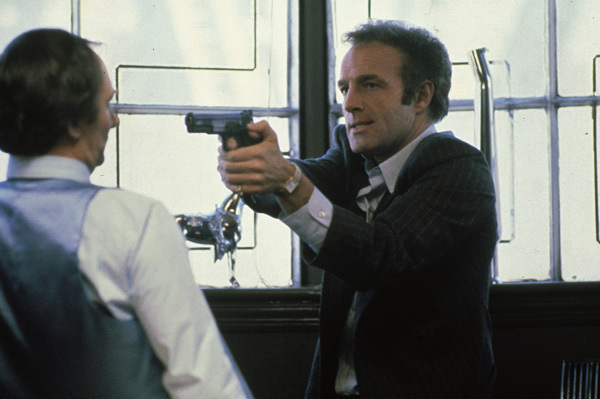

5. Manhunter

Thomas Harris’ novel “Red Dragon” would see two adaptations: starting in 1986 with “Manhunter” and then later in 2002 with “Red Dragon”. For many Harris purists, “Red Dragon” is a superior film. There’s a good case to be made for this. “Red Dragon” is more loyal to the source material, has an astonishing performance by Ralph Fiennes and the film’s intro with a younger (and let’s not forget ponytailed) Hannibal Lecter is gruesomely entertaining.

But while Brett Ratner (and I love the Rush Hour trilogy) does a good job with the material, Michael Mann is the more interesting one. It has a singular style, clinical yet dreamlike. It as an atmospheric synth score and creepy performances from Tom Noonan and an underrated Brian Cox as Hannibal Lecter (whose last name in this film is Lecktor).

The story, if you don’t know, is about a serial killer known by the name of the ‘Tooth Fairy’ (Tom Noonan) who murders whole families during a full moon. FBI agent Jack Crawford (the late great Dennis Farina who also starred in Mann’s “Crime Story”) seeks the help of former agent Will Graham (William Petersen), a criminal profiler with an unusually strong ability to get inside the minds of serial killers.

Graham agrees, despite having retired after nearly perishing at the hands of another serial killer by the name of Hannibal Lecktor (Brian Cox). As the case progresses, Graham discovers that he needs the counsel of Lecktor in order to find the eponymous ‘Tooth Fairy.’

Rather’s version opts for a throwback to an old-fashioned psycho-thriller, close to Hitchcock’s “Psycho” in that regard. Mann’s version, on the other hand, seems genuinely invested into the damaged mind of the FBI hunter and the disturbing mind of the serial killer. I wouldn’t say Petersen is a better actor than Norton, but his performance, more detached and brooding after years of researching nightmarish minds, is more believable. In comparison, Norton just seems too down to earth, you wouldn’t believe he delved into such darkness.

Mann’s version is undoubtedly an 80’s product but that’s also part of the charm. It’s still has Mann’s ethereal quality, it’s not just satisfied being a simple crime-thriller. These characters are more than their story archetypes. It’s not just the agent and the monster. It explores the duality of ourselves with who we pretend to be. Are really really like this or did we become like this along the way?

Will Graham is a family man, someone more at home with a loving family, yet in order to catch the bad guys, he must delve into their minds and empathize with the monster. It’s a dangerous abyss, treading the minds of monsters. The monster itself is strangely human. He falls in love and he wants a normal life, but his disturbed mind won’t let him. When he feels betrayed, the monster returns and eats whatever humanity is left. The showdown between the manhunter and the monster is doused in bullets and gore. Only one of them finds salvation in the end.

This is the muck of the world, the senseless destruction of the human animal. It’s not about good or bad. Your codes don’t matter. There are no rules when it comes to evil. You can still die needlessly even if you did everything right. It’s easier to catch a bullet than to live a long life.

4. The Insider

In Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing”, the film’s protagonist Mookie (also Spike Lee) is told by the local drunk, Da Mayor (the late great Ossie Davis), to do “the right thing.” At the end of that film, there’s moral ambiguity; you’re not entirely sure whether Mookie did the right thing.

Was his act of vandalism necessary to save the owners of Sal’s Famous Pizza? Or could there have been another way? While the pizzeria goes up in flames, we get a close-up of a picture of two civil rights leaders with a similar mission but who used different language and methods: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. This illustrates not just the ideological divide between these two legendary men, but to the viewers as well, whatever side you’re on.

This is not the case with Michael Mann’s “The Insider”. The characters of this drama know very well what the “right thing” is. They have been thoroughly warned of the consequences should they abide by them. It’s much easier for them to move on, avoid doing the right thing and live their lives succinctly. Jeffrey Wigand (a brilliantly understated Russell Crowe) could have taken his leverage package, continued his teaching job and ignored the calls of CBS producer Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino).

Bergman received a mysterious package containing technical inside information of an illustrious tobacco corporation. He wants Jeffrey to translate the technical jargon. It soon becomes clear, however, that Jeffrey knows much more compromising information, and it’s even more clear when Jeffrey is called back to his former boss Thomas Sandefur (a reliably slimy turn by Michael Gambon) to renegotiate his final contract. When Jeffrey feels that he’s being followed and surveilled by the company, he decides to become a formal whistleblower, paying for it with great personal loss.

There’s no exciting gunplay in this film – the action relies fully on the performances. Mann unsurprisingly fills the cast with heavy weights; Christopher Plummer as the fiery and legendary reporter Mike Wallace, Philip Baker Hall as the morally compromised head of CBS Don Hewitt, Bruce McGill and Colm Feore as crusading litigators, Gina Gershon and Stephen Tobolowsky as corporate lackeys, and even Rip Torn appears as John Scanlon, a corporate figurehead of CBS. But it’s Crowe’s sensitive and fragile turn as Wigand that truly elevates this film.

Both Bergman and Wigand are fighting against malicious corporatism, but it’s Wigand who nearly loses everything in the process. Bergman, realizing the story will be compromised by CBS in fear of losing a precious merger deal, deals with the guilt of not wanting to let down Wigand but his only sacrifice is his personal ethics, while Wigand ends up all alone in a hotel room, drinking his sorrows, pondering whether he should jump out of a window.

Even with no bullets being fired, the film is suspenseful from beginning to end, with the tension rarely letting up. We feel the paranoia and stress that Wigand is going through and a part of us wishes he would just go home and leave all of this in the past.

This being based on a true story, it’s not accurate on every front, but the film admits this at the end with a disclaimer stating that they dramatized certain events. The real Mike Wallace has stated that at least two-thirds of the film is accurate – unsurprisingly, he didn’t agree entirely with his portrayal.

“The Insider” would be a flop at the box-office, the subject matter seemingly not as exciting as his other films, but this fact shouldn’t keep you from seeing it. It is a brilliant film which showcases that Mann can weave a brilliant narrative from a character drama without needing expansive action set pieces.

3. Collateral

There’s a poem by Charles Bukowski called “The Night You Fight Best” – it’s one of his many beautiful poems and is perfectly applicable to Mann’s masterful film “Collateral”. The story takes place mostly in the dark of the night, where two men are fighting for their lives. Most likely they won’t make it through the night; they ponder their existence, they make excuses for themselves, they act as flawed humans do. Like in the poem, weapons are pointed at them, reason gets lost, the game is fixed, the crowd screams for their blood.

It tells the story of a cab driver, Max (Jamie Foxx), who is forced drive around a hired assassin, Vincent (Tom Cruise), to his designated targets. It’s not a friendship, it’s an understanding. Along the way, through the hail of bullets and death, they discuss the meaning of it all; to Vincent there is little meaning, the human is irredeemably flawed, the murder of a random thug is meaningless.

To the good-hearted Max, who doesn’t live in the nihilistic world of Vincent, life means something. Max asks him what is driving him, and Vincent replies by telling Max that he’s a lost dreamer. ”Don’t talk to me about murder,” Vincent begins, ”what the fuck are you still doing driving a cab?” Vincent is indifferent – there is no why, no reason, he just gets with it. The universe is massively great, we are taken hostage by this enormous space. Vincent tells him the story of a man who died in the subway whose body was there for six hours and nobody noticed him.

The film’s most pivotal scene has them encountering a lost coyote; they gaze at this beautiful creature before it walks away. They drive on, perhaps knowing that they should turn back. According to Navajo folklore, coming across a coyote along your trail means something terrible will happen to you. In the end, when one of them perishes, the dying man asks the survivor if somebody will even notice him…

“Collateral” is the last great Michael Mann film. While his follow-ups certainly have cinematic merit, and have the aspects that made “Collateral” great (particularly the grain digital camera and shoot-outs), none of them were as perfectly assembled. To me, “Collateral” is the first part of Michael Mann’s holy trinity, followed-up by “Thief” and ending (unsurprisingly) with “Heat”.

2. Thief

When Nicolas Winding Refn’ “Drive” came out, everybody seemed to think that it was a spiritual remake of “The Driver” by director Walter Hill. It certainly derived some inspiration for this, but I perceived very early on that the promotional posters for “Drive”, with its pink 80’s font, seemed to be an ode Mann’s 80’s masterpiece “Thief”.

Despite “The Driver” being similar to “Drive” in that it stars a reticent driver, “Thief” is much closer to the spirit of “Drive”. Both are existential mood pieces as much as they are crime films. Both films are about damaged men who are extremely good at something, so much so it defines them. They are afraid to be anything else because to be anything else is to be lost in the void. They fear the void so much they have to live in this world, they have to do what they do, even if it kills them. One is a driver, the other is a thief. Both are betrayed by mobsters, and both find salvation through the love of a woman.

There is brutal, sometimes shocking violence in both. There is a sweetness underneath this sleazy world. It’s not just full of thugs, it’s full of lovers, too. In both films, we are accompanied with synth music, and at times it seems rather cheesy, but it works perfectly because it illustrates what these hard men really want. In their world, there is no room for sentiment, but in their hearts, they want things to be this cheesy. They don’t want to be badasses anymore. They don’t want to deal with thugs, they want to stop looking over their shoulder.

There are father figures in both films: Shannon is a sleazy auto-shop dealer played to perfection by Bryan Cranston; Okla is a dying thief and mentor who desperately wants to spend his last days in freedom, movingly performed by pot-smoking legend Willie Nelson. They both have great villains: in “Drive” it comes in the form of Albert Brooks wielding a sharp switchblade and no eyebrows, and in “Thief” it comes in the form of Robert Prosky, a welcome late-bloomer who made his film debut with this film at the age of 50.

While Brooks dispatches several thugs (including Cranston) in a very gory fashion, Prosky’s monologue to the “Thief”, the moment when he reveals his insidious nature – while the body of Frank’s buddy Barry (James Belushi) is being dissolved in acid – is terrifying.

James Caan even puts his out his greatest performance in “Thief”, most notably in the diner scene, which is Caan’s own self-proclaimed proudest moment. In this scene he pours out his soul to the woman he has fallen for, a damaged waitress by the name of Jessie (Tuesday Weld). In the backdrop, through the window, we have the lights of cars disappearing in the darkness.

Frank knows he’s a scumbag and she deserves better but he needs to convince her that he’s worth her time. But he refuses to lie and is honest about having done hard time: ”Some other things. I was 20 when I went in, 31 when I come out. You don’t count months and years. You don’t do time that way. You gotta forget time. You gotta not give a fuck if you live or die. You gotta get to where nothing means nothing…”

Perhaps it was because how wired Caan really was – this was in a period of heavy cocaine use – but it’s a brilliant scene in every way; direction, writing and performance.

Like many of Mann’s explorations of the criminal underworld, there’s an authenticity to it. The screenplay was adapted from a novel by Frank Hohimer, a real thief. The safe-cracking has a massive technical aspect to it; it’s hard work, sweaty, it’s like a normal job. The way the characters speak, you feel that they’ve lived in this world for a very long time.

“Thief” is simply a masterpiece, a beautiful product of its time, that manages to perfectly combine heart and grit at the same time. If it wasn’t for the next film on this list, this would have been Mann’s greatest film.

1. Heat

The basis of “Heat” was inspired through a personal friendship between a former cop and then-aspiring writer Chuck Adamson. Much of what you see on screen is based on the real exploits of this Chicago cop chasing notorious bank robber Neil McCauley. The classic dinner scene in “Heat” that pitted two acting legends together was based on a real conversation confrontation Chuck and Neil had. Though the conservation didn’t hit on the existential heights as in the movie, the similarity was undeniable: ”You realize that one day you’re going to be taking down a score,” said Chuck, ”and I’m going to be there.”

”Well look at the other side of the coin,” said Neil matter-of-factly, ”I might have eliminate you.”

”I’m sure we’ll meet again.”

This would be the last thing Chuck said to Neil. It almost sounds like a Hollywood film, but this was real life. These people really existed. They didn’t have a personal vendetta against each other, they had mutual respect for each other’s professionalism. This was all just part of the game.

But this wasn’t child’s play – this game of cops and robbers had real guns and real stakes. Chuck had been in the can for more than two decades and he wasn’t going back. Regardless of each other’s respect for one another, when either of them were cornered, they would not hesitate. The story between these two men ended just the same. There was a chase, a gunfight, and it was Neil who would end up gasping his last breath.

In the film it’s a little more dramatic. Neil has a chance to flee from justice and live the remainder of this days with the woman of his dreams, but when he receives word of the whereabouts of a psychopathic criminal who endangered his life and even murdered one of his trusted colleagues, he can’t help himself and sets forth to settle the score. Neil had a chance to start anew, but he fucked it up. Chuck knew this about the real Neil as well; this was a man who could not be rehabilitated. It was always going to end like this.

The film plays with this notion of these men with certain codes, yet never makes them noble because of it. In fact, it’s these very codes, despite how far they can bring them in their professional world, that become their undoing. Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) plays the obsessive cop, and he’s the man in this world but in his private life, he’s a complete failure.

It’s just as his estranged Justine (Diane Venora) says: ”You don’t live with me, you live among the remains of dead people.” This is a woman who would eventually have an affair just to get his attention. This is a man whose ghostly presence around the house would lead to his daughter attempting suicide.

Neil, on the other hand, pretends to be detached from any emotional commitment. You could say his downfall came when he fell in love with Eady (Amy Brenneman). But even before this, it was apparent that he wasn’t the cold-hearted man he presented himself to be.

There was the impulse of vengeance, born out of life. He went back to kill Waingro because he was the one that brought ‘heat’ on him and his crew, which was the beginning of their downfall. He was the one who murdered his friend Trejo (played by legendary ex-con Danny Trejo). Waingro needed to die not because he broke some sacred code, but because he instigated the demise of his criminal family.

Vincent and Neil are two archetypes stuck in their roles. In a lesser film, they act the way they do because the script tells them to. But in a Michael Mann film, it feels coherent to the universe, thanks to the multitude of three-dimensional characters. In fact, you actually wish the film would be longer just so you can discover more about these rich characters. These characters cannot transcend their roles, just like most people can never change.

When Vincent clutches Neil’s dying hand, he looks away, seemingly lost as Moby’s beautiful “God Moving Over the Face of Water” plays in the background. Part of him is angry at Neil for making him do this, yet he knows that it could not be helped. He will mourn Neil’s death not because he loved him, but because he needed him. His role in this world makes little sense without him.

This is the brutality of fate, a predestination not based on the lofty promise that friends will come together, that their connection will be their salvation. Instead, based on the neurotic machinations of their own damaged souls, these friends will end up destroying each other.