8. The Rain People (1969)

After a series of mixed bag efforts in his early filmography, “The Rain People” feels very much like the first proper Coppola movie. The filmmaker was growing tired of being thrown from job to job without much investment in his subjects, whilst also being inspired by the new type of cinema emerging in the late 60s.

The director, a gang of eager actors and a skeleton film crew hit the highway with a vague script idea and a passion to create a ‘road movie’ with an emphasis on a character study with melodramatic undertones. The film didn’t catch on with audiences (ironically the ‘road movie’ genre would flourish like a house on fire the next year, with “Easy Rider”), yet the film ignited something in Coppola that would propel him forward into his peak career work soon after.

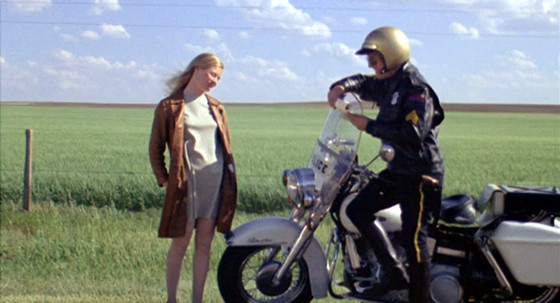

Shirley Knight’s troubled housewife wakes up one day and takes off on a road to nowhere, coming across and taking in similarly damaged souls, like James Caan’s mentally challenged ex-football star and Robert Duvall’s widowed patrol cop. Knight plays a rare female lead in a Coppola movie, full of life and conflict, even if her constant hesitation to aid Caan’s character grows grating – her bad decision only helps make her feel like a fully formed and honest character.

However, Caan, in his first proper supporting role, is the true scene stealer, playing the sweet-natured yet physically opposing male counterpart, who Knight first romances then nurtures. It showcases a range and playfulness the actor rarely showed, after being typecast as alpha males throughout the majority of his career. Duvall also makes an incredibly strong impression in his brief screen time. The casting of both these actors is pivotal to Coppola’s career since they each would become lifelong friends and collaborate on several movies down the line.

Storywise, though, the plot can feel as lost as the main characters – sort of floating along from town to town and abruptly ending in an unnecessarily downbeat ending that feels more like a quick way to wrap things up, rather than a satisfying conclusion to the involving character arcs. Still, Coppola truly feels alive behind the lens, generating a haunting visual style (especially in the flashbacks), mixed in with some genuine location work and engaging raw performances.

It’s the the most focused and significant of his pre-”Godfather” period, and in terms of quality it’s not his “Mean Streets” but more akin to Scorsese’s “Don’t Come Knocking” – a rough-edged film with pacing issues but chock full of energy and hints of what a powerhouse talent the filmmaker would soon become.

7. Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988)

This biography centred around Preston Tucker, the ambitious yet doomed car pioneer, was a long-time passion project for the Italian-American director. Yet it stagnated in false start after false start before Coppola’s longtime friend George Lucas fit the bill – repaying the director’s guidance and financing of his earlier pre-”Star Wars” work.

One might question Coppola’s persistent affinity for the subject matter, yet by watching the film, its connection is soon completely laid bare – Tucker was a boisterous and vocal dreamer, a loving family man, and a person who was willing to put it all on the line for a vision that not many (especially ‘big business’) shared. All personality traits completely sync up to Coppola’s id, and as the interesting untold slice of Americana rolls out, one comes to realise it might be the director’s most personal and honest film he’s ever made – reflecting on a career ups-and-downs, it’s as much about Coppola’s life as it is about Tucker’s.

Jeff Bridges plays the centre role with flawless depth and charisma, encapsulating all aspects of the layered character – the consummate showman, the loving father, and the stubborn and dangerous businessman. He’s got fantastic support by the late Martin Landau as his partner in crime, as well as Joan Allen and Frederic Forrest in other solid parts.

The direction flows like its smooth jazz soundtrack – a lush free-flowing camera style that’s full of inventive on-set transitions and split screen. Coppola’s fantastic perfectionist attitude for every minute detail and planned camera shot is intoxicating, and the period’s architecture and atmosphere are utterly brilliant as well. The energy brought to it greatly helps what could’ve been a vanilla biopic on paper and in turn, it never threatens to collapse into bland territory.

An unavoidable flaw, though, is that one might be hard-pressed to become as enamoured with Tucker’s dream, or sympathise with his tough personality as much Coppola does. Still, the director does a good enough job of engaging us with the material in this unique piece of American history that is surely the director’s most criminally overlooked film to date.

6. Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Certainly Coppola’s full-blown dive into horror cinema goes for broke so often it teeters on silliness – especially its first third that is focused around the titanically miscast Keanu Reeves as a mild-mannered accountant stuck in Transylvania, which borders on unintentional comedy (or did Coppola intend it?). It must be said, though, that there’s so much to admire about this deliciously excessive adaptation of Bram Stoker’s classic novel, told with such ardent enthusiasm for its subject matter, that it’s difficult not to get caught up in proceedings.

A rare case of a studio pumping a huge budget and A-list talent into a horror movie, Coppola delivers in spades with a style that’s relentlessly excited about what it wants to achieve and happily succeeds for the most part – a love letter to several eras of genres past (Hammer, Bava, and German Expressionism all get heavy shoutouts) with every frame painstakingly and beautifully made in an industry just before CGI evaporated the type of practical artistry showcased here.

Yet it also succeeds in being the most definitive take on the classic and often-told tale – managing to be atmospheric, horrific, sexy, and most importantly, romantic, with its fresh take on the proceedings being a tragic love story instead of hammering us over the head with the ancient morality infused in the book.

With Coppola blowing on all cylinders as director, thankfully its cast (aside from the young Reeves) is incredibly game for the ride – Anthony Hopkins relishes the ham with his enjoyable take on Van Helsing, Winona Ryder is in strong form in a demanding role as Mina, and a special mention has to go to Tom Waits as the hilariously unhinged Reinfield.

With that said, every Bram Stoker adaptation really hinges on its Dracula and in this case they’ve got a flawless winner – Gary Oldman, cinema’s most versatile chameleon performing in an era where he could do no wrong. He’s spellbinding as the Count in every single form the fantastic make-up work demands he inhabits, from skin-crawling old leech, to terrifying wolf-creature, to dark and exotic seductor.

The movie is a blast from beginning to end – regardless of some stumbles and lack of genuine scares due to its hyperbolic nature, it has plenty of shocks, excitement and beauty to make up for it, in a very different type of movie from the experienced maestro and truly a film that deserves more for plaudits than it gets.

5. Rumble Fish (1983)

While Coppola’s first S.E. Hinton adaptation played it safe with a classical grounded style that slightly hampered its potential, his second go around is the polar opposite – deploying an eclectic aesthetic that hints at German Expressionism, early Orson Welles and the Nouvelle Vague, this pulpy youth tale is vibrant with energy. Told in stark black-and-white photography that creates a hyperreal city filled with endless grimy ghettos and inhabited by lowlifes, it’s an engrossing and fascinating visual landscape.

Taking “The Outsiders” standout Matt Dillon and placing him front and centre was a smart move – the actor’s appealing bad boy image is turned on its head as the impressive young performer plays Rusty James, a meathead street tough that begins seeing the rest of the world quickly pass him by, and is constantly overshadowed by legendary brother Motorcycle Boy (played with soft-spoken intensity by a peak Mickey Rourke).

Therein lies the engrossing dynamic in a story of brotherly love and scorn (one close to Coppola’s own heart), a mesmerising journey with a handful of playful and haunting set-pieces (the stylish opening knife fight, Dillon’s out-of-body-experience montage), colourful appearances by pre-breakthrough Laurence Fishburne, Nicolas Cage and the mesmerising Diane Lane, and ultimately it all leads to a devastatingly tragic conclusion.

Coppola goes for broke in terms of style, but unlike several of his other experimental ventures, this one refuses to go off the rails or drown its excess due to themes and pathos that are heartfelt and effective, making this ambitious studio assignment worthy of standing next to his best and strongest work.

4. Apocalypse Now (1979)

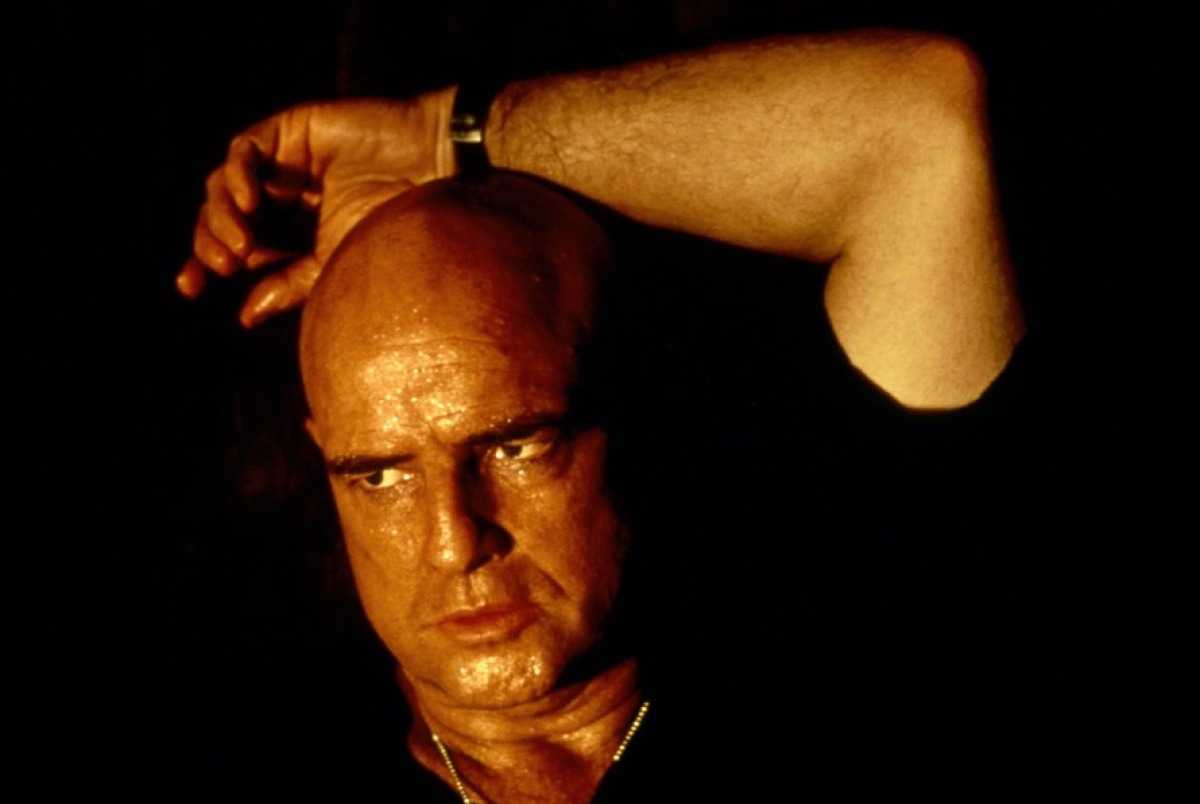

“This is the end… the end, my friend…” With Jim Morrison’s haunting lyrics accompanied by the striking image of a slow-motion napalm attack turning a forest into scorched earth, viewers are gripped by the neck and dragged deep into this nightmarish treatise on the human physique. At first meant to be a medium-budget actioner by George Lucas, when Coppola took it over it became an infamously troubled production that almost ruined him not only financially, but also mentally and physically. Instead he emerged out of the Philippine jungles with a landmark classic if not the most iconic war film made about Vietnam.

As we’re treated to Martin Sheen’s deranged captain losing his mind in a hotel room, and then given a kill-mission to take out Marlon Brando’s looney military man, one realises this isn’t your granddad’s war movie. As the audience is sent into the surreal hell of the Vietnamese battlefront, Sheen soon looks to be the most level-headed character as a smorgasbord of eccentrics and sociopaths emerge out the woodwork that fill out a unique journey full of disturbing and surprising imagery, plus non-stop memorable scenes (Hall of the Valkyrie helicopters, Playboy Bunnies, and surfing amongst explosions, to name a few).

There’s also no denying the entire enterprise is steeped in authenticity – not that the director was a war veteran, but it’s less about war and more about the frail human mind, and its treatise on insanity is directly reflected by Coppola’s own descend into madness whilst making the movie itself.

It’s a haunting film and one that’s incredibly taxing to watch with its dark yet oddly humorous experience slightly dragged down by an overlong finale (blasphemy to say, i know). Yet there’s no arguing its mark and power in cinema, and it’s one of Coppola’s towering achievements – as the this film almost killed him, yet the man came out as champion instead.

3. The Godfather Part II (1974)

Made at a time when sequels had a rancid reputation of being quick cash grabs (unless you were James Bond), Coppola’s follow-up perfectly encapsulates what it strived to be just within the title itself – a ‘Part II”, as in the next chapter.

Also playing the smart move of working consecutively as a prequel and sequel, it charts Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone’s ascendence to the throne of America’s mafia, and his rise is a double-edged sword as he loses his family and humanity. This is told in parallel to the story of his father Vito, played by a charismatic Robert De Niro in one of his strongest performances, and charting his tragic beginnings in Sicily to his rise as a criminal in turn-of-the-century New York.

The cold depressing tones of the contemporary storyline is told along with the fascinating palette of the families origins, making for a sublime and vibrant balance that perfectly accents each other and drives home the main plot’s tragedy – essentially both storylines are similar, yet different moral compasses lead the characters toward different outcomes.

Not surprisingly, the cast is sublime all around with both De Niro and Pacino in their peak years (yet sadly unable to share the screen together here). Coppola truly raised the bar for what a sequel could achieve, with this feeling like a true and vital extension of the first movie and not an unnecessary cash grab (cough, Part III, cough). If it is less preferable than the first movie (most argue not), it’s in the heart-wrenching nature of Pacino’s plotline, making it less appealing to return to, but still it can’t be denied that this is essential Coppola, not to mention peak filmmaking in general.

2. The Conversation (1974)

Often cited as one of the great ‘paranoid’ thrillers of the early 70s, it’s successful in that aspect, but the true power of Coppola’s slow-burn gem is a devastating character study centred around Gene Hackman’s isolated island of a man Harry Caul.

Caul is a genius surveillance expert haunted by a dark past, but it’s questionable if that’s what made him such a cut-off figure or if he was always this way. He’s a man who wants to reach out and connect with others, but is woefully unable to, instead finding intimacy through a recorded conversation of a seemingly innocent couple, which slowly unravels a darker plot that spirals Caul’s character into the melting pot.

Inspired by Coppola’s own youth that was filled with anxiety and loneliness (the ‘bathtub monologue’ Hackman recites in a dream is based directly off Coppola’s personal experience), every aspect of the film is flawlessly in sync with the mental breakdown of it’s main character, from the striking image framing him against a post in an abandoned parking lot to his playing saxophone alone at home to a recorded live performance.

It makes for an involving tale that stands as one of the most intimate stories told – we become so ingrained into Caul’s outlook that even his sense of slipping reality becomes the audience’s own. It’s a tour-de-force performance from Hackman and one so successful that it’s baffling that he and the director didn’t return to collaborate again, though one questions if Hackman’s method approach during production made him just as polarising a figure as his movie character was.

It was a rare case where Coppola was able to tackle something deeply personal on a lean budget and running time, a type of cinema he was more interested in making if larger projects hadn’t sidetracked him from this original path. It’s by far his most efficiently told movie, showcasing that by losing his more ambitious indulgences and loftier pretentious it only makes proceedings more powerful and gripping, in this engrossing hidden masterpiece of his.

1. The Godfather (1972)

What can be said about this film that hasn’t been said already? It’s a stone-cold classic that shook cinema in its wake, the ultimate Italian mob story (sorry, Scorsese and Gandolfini), as well as an iconic morality tale that reaches Shakespearian quality.

Going through the checklist of what makes it great, we can first look at the cast – Marlon Brando as the warm yet fierce Vito turned a waning career around into Oscar-winning glory, Pacino made his breakthrough with the quiet yet whip-smart Michael. Add to that James Caan, Robert Duvall, John Cazale – the list goes on with a bevy of ridiculously talented performers turning in some of their most memorable performances.

Then it was a fantastic mix of director and material – Coppola took the job as an assignment after becoming broke from “The Rain People”, an adaptation of a popular paperback, yet he broke the book down into something relatable toward his persona, focusing on the tropes of the Italian-American family and their minor struggles yet big love amongst each other. It immediately pulled in audiences and helped them relate to a story centred essentially around a criminal enterprise.

Also, Coppola’s stylised approach to the material (matched with Gordon Willis’ careful cinematography) results in an elegant, grounded, and involving movie and a classy take on what had (beforehand) been a genre that had was considered B-level and exploitive. It must be remembered that “The Godfather” successfully changed the perception of the ‘crime movie’ forever – making it closer associated with A-list filmmaking and Oscar-winning glory than pulpy genre thrills.

It all leads to a perfect storm of collaborators and material that resulted in a classic movie with dozens of classic scenes (horse head in bed, the restaurant murder, Sonny’s demise) and dialogue that becomes etched into your mind forever. The movie has lost none of its lustre, thrills or heart to this day and is hands down the greatest thing Coppola has made – which is no small feat.