8. Wall Street (1987)

Marxism can adequately diagnose the problems with capitalism; when unregulated it can bring about unprecedented inequality, causing massive division between the classes. In a way you can’t really blame a large part of the population who demand a socialist revolution after experiencing the consequences of laissez-faire capitalism. But as happens with so many great political thinkers, their diagnoses comes without an adequate cure. The cure for capitalism is not communism or a planned economy. In fact, implementing a planned economy will make the horrors of capitalism seem pale in comparison.

This is why Stone’s “Wall Street” is so successful: it’s a deliciously unsubtle but poignant analysis of the greed that swept the 80s and ultimately the future. This might be Stone’s most accurate analysis of American culture. His views on the American intelligence agencies might reek of hubris and even slight paranoia, but his condemnation of the Wall Street culture of the 80s is disturbingly on point.

While never reaching the wit of liberal wordsmiths Aaron Sorkin or Paddy Chayefsky, Stone and his writing partner Stanley Weiser do pen some brilliant monologues, many of them, especially Gordon Gekko’s rant about where the wealth of the richest one percent comes from, are still relevant today.

As most of you will know, Michael Douglas plays Gordon Gekko, the villainous Wall Street trader who takes a naive young trader Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen) under his wing. Budd battles between Gekko’s “Greed is Good” philosophy and his own father’s blue collar wisdom – played by Charlie’s real-life dad Martin.

Despite the usual preachy nature from Stone, this still holds up. Perhaps the trading business is a bit more up-to-date in its sequel, but really, who cares?

7. Heaven and Earth (1993)

Whether you agree with him or not, there’s no question that Stone loves his country. This love is unwavering, and like any love affair, it has its share of madness. He doesn’t trust his government, but he can’t help but hope that one day, our political elite will resemble the ideal.

One day someone will come along who will unite us and will lead us to the America we always dreamed about. This is a man that bled for his country, and saw good men die for a war that led nowhere. A disgruntled veteran, but one who has fallen too deep with the American dream, no matter how many times it has broken his heart.

This is why his best films are his most personal ones. The films of the Vietnam trilogy, starting with “Platoon”, “Born on the Fourth of July”, and in this case, the deeply underrated “Heaven and Earth”, showcase his experiences in Vietnam, the war that took not only the lives but also the humanity of many American and Vietnamese people.

“Heaven and Earth” is his final exploration of the Vietnam trilogy. As in his previous two films, the story is told through innocent eyes, their world ravaged by the onset of an arguably pointless war. Similar to the experiences of Ron Kovic, Stone adapts another biography, but this time from the point of view of a Vietnamese citizen Le Ly (an incredibly moving Hiep Thi Le).

From being violated by the hands of the Viet Cong to the doomed love affair with a traumatized GI Steve Butler (Tommy Lee Jones giving one his best performances), the respect and care Stone brought to her story deserves praise. American cinema rarely delves into the point of view of foreign countries, especially when they went to war with them, and this film proves that it can be done.

6. Born On the Fourth of July (1989)

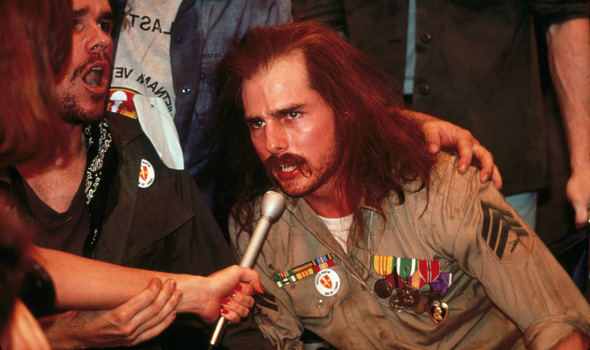

Ron Kovic was the ultimate American poster-boy: God-fearing, loves John Wayne, so patriotic he was even born on the Fourth of July. Eager to fight for his country, he would serve two terms in Vietnam, only to be rewarded by being paralyzed from the waist down.

Returning to the country he loved, he began to wonder about the legitimacy of the war. He would be arrested several times for political activism, but despite his sacrifices, he was dismissed as some sort of radical leftist. He would write a moving memoir; when interviewed, he would speak openly, sometimes even on the verge of breaking down, about his experiences in Vietnam.

Another veteran would contact him and write a movie alongside with him: Oliver Stone. To cast Kovic, Stone choose a star: Tom Cruise. Alongside his performance as crazed sex guru in Magnolia, this is Cruise’s greatest role. He’s not just being Mr. Cruise here – he’s an actual character. The perfect embodiment of American idealism, whose dreams are crushed by the madness of war. His performance even moved the real Kovic so far that he gave him his own Bronze Star.

This film would give Stone the honor of being one of the few directors to win a second Oscar – handed over by cinematic legend and his earlier film school teacher Martin Scorsese.

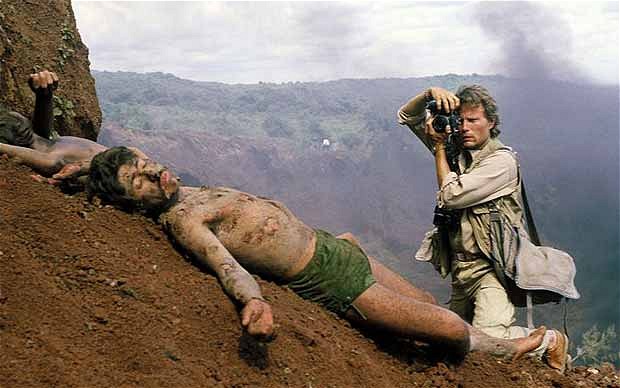

5. Salvador (1986)

Salvador has the kind of madcap energy that is sorely missing from Stone’s later work. Back then in 1986, Stone wasn’t the infamous contrarian we know now, but a filmmaker struggling against the various forces that were compromising his vision. The studio wanted to cut pertinent scenes, there were financial issues, and the subject was always controversial. There is a Gonzo nature about this film; it’s wild, unrefined, and as always, deeply subjective. This was the beginning of Oliver Stone as we know him today, and his previous two horror fares would soon be forgotten.

The film details real-life journalist Richard Boyle (James Woods) covering the Salvadoran Civil War, who becomes personally involved when he becomes reacquainted with a love from the region. But it’s not just the brutal right-wing military death squads that are standing in his way – it’s also the tragically misguided foreign policy of the Americans who haven’t learned anything from the failure of Vietnam.

As always, Stone embellishes so much that one cannot consider this serious historical fiction. The evil-doers are demons, and the victims are either angels or misunderstood. Stone has even admitted that the scene where leftist guerrillas execute prisoners had been embellished in order to bring some balance to the film.

But it’s nigh impossible not to be moved by Boyle’s journey, aided by a perfectly-cast Woods, as he desperately tries to make sense of the horrific situation and save the woman he loves. Though a part of you still wishes they would make a Gonzo-style road movie starring Richard Boyle and his sidekick Dr. Rocker (played by a hilarious James Belushi).

Stone would follow this up with what would be his masterpiece, “Platoon”.

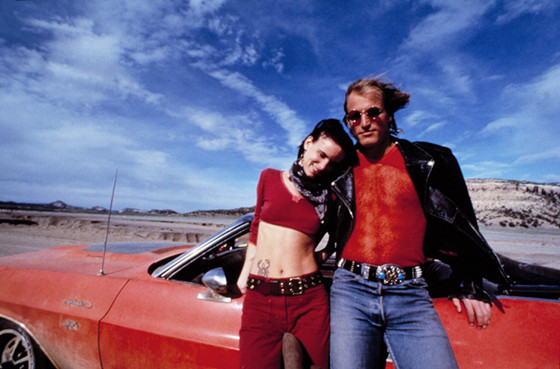

4. Natural Born Killers (1994)

It’s unbelievable how many people admire the obvious villains of the world. You’d think that after a span of time, people would recognize the villains. But still, a lot of people buy into their propaganda. These tyrants don’t care about the freedoms we enjoy; they would take it away if it would benefit their reign. Human rights mean something to them. It’s all about them. It’s all about power. Yet the people prefer to see a different image.

In Oliver Stone’s unhinged masterpiece “Natural Born Killers”, we have the masses admiring two mass murderers, Mickey (Woody Harrelson) and Mallory (Juliette Lewis), seeing something intimately human in them. They want these people to not be merely demons – they want them to be like them. It’s better to believe in anti-heroes. It makes life much easier and it makes for a better story.

The media, represented here by tabloid journalist Wayne Gale (a wonderfully goofy Robert Downey Jr.), capitalize on these two fiends, peddling the most exciting narrative, getting people hooked on the gore and violence. This movie was made after the O.J. Simpson hyped murder trial, which not only indicated that there was something wrong with the justice department, but that there was something deeply wrong with the American people. They were too eager; the case was too sensationalized and they didn’t care.

The movie seems, in typical Oliver Stone fashion, completely over the top, but this was made in the 90s and we are now in the 21st century. Is this fantasy or does this come closer to reality than we dare to admit? We are lost in the void of endless information. We have all the capabilities to uncover fake news yet here we are; so many admire the villains, so many wish they were like them.

The film is madness incarnate: the camera is never straight, the film switches from color to black and white just to illustrate the subconscious, scenes are lit in sickly green neon, there is animation, stock-footage, even a studio audience.

Sometimes the film is horrifically violent and disturbing, other times it’s hilarious – in particular, an unforgettable supporting turn by Tommy Lee Jones as prison warden Dwight McClusky makes possibly one of the funniest side characters in an Oliver Stone film. The late and immortally great Rodney Dangerfield, the comedy god of one-liners, plays his only dramatic role as the abusive father of Mallory, in a sequence played in traditional sitcom fashion that might be the most disturbing scene of the film, and that’s saying something.

As could be expected, the film was heavily misunderstood, even accused of glorifying violence. There would be court cases about this film, the claim being that it incited violence. A psychotic mind might find kinship in this film, but you can never blame an artist for how it inspires them. If they were already so far gone to begin with, they were just waiting for a trigger.

“Natural Born Killers” is a film unlike any other. It’s from a filmmaker at the height of his game. It’s an uncompromising, wonderful, insane piece of art.

3. Nixon (1995)

The sad truth is that Richard Nixon, the 37th president of the United States, was probably far worse than how he is portrayed in Stone’s biopic. In real life, something we don’t get to see in the film, Nixon, along with his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, interfered with the Paris Peace Talk, continuing the war in Vietnam, just to make his campaign promise still viable in 1968. It would have been very easy for Stone to completely demonize the infamous crook. Undoubtedly if he went down that route, many would celebrate it while others would call it typical left-wing bias.

The film, however, does retain Stone’s slanted view of the world, even if he refuses to portray Nixon as a monster. The monster in this film is the system, which eats the hearts of people and turns them to darkness. We have the usual smoky back-room scenes, even a very ludicrous one where a group of powerful men suggest to Nixon – this was before Nixon decided to run for president – to go after the presidency to relieve Kennedy from his position.

When Nixon states that nobody will beat Kennedy, the men give each other a look and then state ”what if he doesn’t run?” The implication is obvious. Another scene involves a conversation between Nixon and CIA director Helms (played with sinister perfection by Sam Waterston) where they talk about evil. Stone makes sure we perceive the Central Intelligence Agency as evil by turning Helms’ eyes pitch-black for a moment (note: this can be seen in the Director’s Cut).

As you can see, Stone’s approach will not satisfy history buffs, but it does make for a fascinating and sometimes moving viewing, courtesy of Anthony Hopkins’ haunting and unforgettable turn as Richard Nixon. We have a misguided and insecure man who wanted to make his mark in the world, but who let his demons get the better off him. Through black-and-white flashbacks we get glimpses of his oppressive conservative household; we see a boy who desperately wants to please his extremely religious mother (Mary Steenburgen). We see alcoholism; we even see a weeping Nixon, praying to God for help.

The cast is once again star-studded, and to name them all would take awhile. But the most memorable are Joan Allen as Pat Nixon, Bob Hoskins as J. Edgar Hoover, Paul Sorvino (doing a perfect accent) as Henry Kissinger, Powers Booth as Alexander Haig, J.T. Walsh as John Ehrlichman, and David Hyde Pierce as John Dean. Apart from “JFK”, perhaps, this might be the best cast in an Oliver Stone film. There’s simply not one unfamiliar face on screen and they all do a fantastic job.

Ultimately, Nixon’s complicated legacy made the likes of Stone ever more relevant: if there’s one person who could be blamed for the rise of the public’s mistrust of the government and conspiracy theories, it’s Richard Nixon.

2. JFK (1991)

Here it is: the big enchilada of conspiracy thrillers. There is so much right about this film that one could call it a masterpiece. It’s a pitch-perfect blend of sharp editing, suspense, and acting. It made the world wonder about the truth, and question whether the deep state had been involved in murdering the president. The case is made so beautifully in this film that it’s hard to not question the truth and get swept away by its reasoning.

It’s such a well-made film that it’s frustrating knowing that almost none of it is true. There was no conspiracy. Lee Harvey Oswald did it. The bullet was not magic. The more you look into Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner, the main star and admittedly the worst actor in the film), the more you realize that his gay-conspiracy theory surrounding Clay Shaw (played by the always reliable Tommy Lee Jones) is laughable but also dangerously liable.

David Ferrie (a wonderful paranoid Joe Pesci) died of natural causes and was not murdered. There is no deep state. There was no Mr. X (the person he is based on, Col. L. Fletcher Prouty, has made several other ludicrous claims). Even Stone’s cherished beliefs that the assassination of John F. Kennedy was the loss of innocence for America is absolutely rubbish. There was no Camelot; the Kennedy lineage is filled with tragedy but also abhorrent crimes. His death did not mean that hope was lost for America – America was as good and evil as it had been before him.

So if you can swallow Stone’s hyperboles and downright lies – and maybe even madness, for that matter – you are in for some powerful filmmaking. It feels like “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” but in this film, Mr. Smith awakens in a nightmarish paranoid Americana. Stone stacks the supporting cast with actors who all give memorable performances, from Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Gary Oldman, Kevin Bacon, Donald Sutherland, Joe Pesci, Sissy Spacek, Michael Rooker, Laurie Metcalf, Wayne Knight and an unforgettably sleazy John Candy.

Even if it’s all bullshit, it’s stellar cinematic bullshit.

1. Platoon (1986)

The introduction to Kurt Vonnegut’s classic novel “Slaughterhouse-Five” details the novelist’s struggle to write a novel about the war. As a veteran of World War II, he reunites with an old war buddy to find inspiration. It soon becomes clear to him that he found nothing heroic or glamorous to write about the war. They were all children sent out to kill or be killed. It’s as the second part of the title states: ”The children’s crusade.”

“Platoon” is the same way; we see young men on the battlefield losing their innocence for a war that, compared to what was at stake in World War II, was pointless. Stone, who wrote and directed this film, is a veteran himself and much of what’s on screen is based on his experiences. The first war movie written and directed by a man who served in that particular war. Like Vonnegut’s great novel, there’s nothing glamorous or heroic about any of this; it would be one massacre after another.

To understand Oliver Stone and his never-ending resentment against the American establishment, we have to understand his part in the war. He joined in part for symbolic purposes: as a rite of passage, as great men are often shaped by their service in the military, but also to rebel against his conservative father, hoping to prove to him that he has become a man. In his 15 months of service, he would find inspiration for what would be his defining film: “Platoon”.

But it could have been very different; like so many vets he returned to civilian life as an emotionally damaged young man. He could have very well been one of the many veterans struggling to find his place, still enraptured by their experiences of combat. We need meaning in our lives, even if we have seen enough things that make us question whether there is any meaning to be found. He would find it in the art of cinema – studying in film school under the likes of Martin Scorsese.

This is why Stone is so direct and doesn’t fuck around. This is why there’s such an urgency to his films: he saw men perish under a seemingly pointless war. He saw the consequences of blindly following orders and believing everything the establishment tells you. He saw the loss of humanity in his combat troops; the infamous village scene was based on Stone’s actual experiences. He saw the brutality of some of his commanding officers – Sergeant Barnes (Tom Berenger) was based on a real person.

Even after all these years, “Platoon” still remains powerful. There’s still the occasional awkward preachy dialog – especially from the Christlike sergeant Elias (Willem Dafoe) – but it still holds true to this day. The shoot was a miserable one; the actors were tired, stressed, and even Stone, being reminded of the horrors of war, suffered post-traumatic stress. This was how real it was. The result would be one of the greatest depictions of war – as well as being one of the greatest war films of all time.

Author Bio: Chris van Dijk is a writer and self-proclaimed cinematic-connoisseur who started his unhealthy obsession with film at a very young age. He’s famous for being an incredible slob, taking himself way too seriously and getting along brilliantly with anyone who agrees with him. If you are interested in his writing you can follow his weekly blog at https://welcometothehumanrace.wordpress.com/. If you are interested in his obnoxious tweets you can follow his account at https://twitter.com/stubbornwaves.