4. Days of Heaven (1978)

Malick’s second feature film is a beautiful work, with the wonderful, early 20th century countryside as its backdrop. It stars Richard Gere as Bill, a young tramp on the run after a violent incident in an urban factory job. He’s accompanied by his lover, Abby (Brooke Adams) and his younger sister Linda, played by Linda Manz.

They flee into rural Texas, and Bill takes a job working for a farmer played by Sam Sheppard. Told the farmer is sick with a terminal illness, Bill and Abby pretend to be siblings, with hopes that Abby can seduce and marry the farmer, earning the couple his inheritance so they can get a head start back on the road.

The plot is simple, soapy even, but Malick’s ode to the Texas countryside and portrait of early 20th century America is intriguing, visually stunning, and characteristically contemplative. Classical music plays in the background of several key scenes, another Malick signature, perhaps proof of how much of an old soul he is and even was at age 35.

Days of Heaven marks a confluence of many Malick regulars, like the use of natural lighting, religious themes, romantic love that oversteps the boundaries of traditional marriage, and his home state of Texas. Malick directs Richard Gere and Sam Sheppard to give some of their most memorable performances, and it was with this film that he proved he was no one-hit wonder, but one of the greats.

3. Badlands (1973)

Malick’s directorial debut remains one of his best works, almost half a century later. Badlands introduced the world to Sissy Spacek, three years before she’d play the tile role in Carrie, and more importantly, introduced the world to Malick himself.

Though the films lacks flashiness and gimmicks, it’s so advanced and insightful we often forget that it is someone’s directorial debut. But at 30 years old, Malick was ready to leave his footprint in the world of cinema, and blew many away with this film.

Spacek stars as Holly, a baton-twirling, 15-year old girl in love with Kit, a garbage man ten years her senior, played by Martin Sheen. It’s amazing how both characters so convincingly never seem bothered by the apparent weirdness of their relationship, which was Malick’s way of indicating to us that he’d spend a career taking hits at traditional ideas of love and relationships.

Legal complications lead the two lovers into the countryside, similar to Days of Heaven, and Holly’s naïve, innocent love for Kit is at odds with Kit’s criminal behavior. Malick forces us to question whether Holly is an accomplice to Kit’s crimes or weather she is too innocent to ‘get it,’ further advancing questions on the ‘wrongness’ of their relationship. Is this a beautiful, twisted love story or is it just really gross? 44 years later, we’re still wondering, and Badlands has become a classic 1970s American film.

2. The Thin Red Line (1998)

20 Years after delivering his impressionable Days of Heaven, Malick disappeared, giving no indication weather he ever planned on returning. His resurrection in 1998, The Thin Red Line, was an incredible turning point for his career, and went down in film history as one of the most out-there World War II films of all time.

The Thin Red Line rejects several notions of what a film should be, especially an American film. It turns down the traditional protagonist for an ensemble of narrators, all American soldiers in different ranks, engaged together in various island-hopping battles in the Pacific.

Its all-star cast includes Nick Nolte, Sean Penn, Jim Caviezel, Elias Koteas, John Cusack, Adrien Brody, George Clooney, John C. Riley, Jared Leto, John Travolta, and Woody Harlson. Their fleeting attitudes are conveyed throughout the film, and we get to know every character in his own context.

As mentioned before, Malick’s stubborn research for the film resulted in beautiful, memorable natural imagery. The opening sequence, in which Jim Caviezel’s Pvt. Witt flees his battalion and lives with a tribe of islanders, is particularly memorable. The film opens underwater, the frame filled with beautiful, joyous, illuminated blue. Most of Malick’s work humbly nods to nature, but this film may do it the best (or second best).

What’s more, even in such a high stakes setting, Malick knows what he’s doing when it comes to delving in themes of mortality. One second, a soldier is throwing himself onto a grenade to save his friends, evoking tears and disgust as we watch him scream in agony; another, a soldier is kept alive merely by the thought of reuniting with his wife.

The emotional and daring images throughout the film meaningfully ponder on themes of masculinity; the sensitivity of and towards the men in this film deviate it heavily from the war film genre.

The Thin Red Line is about as out there as a WWII movie can get; released the same year as Steven Spielberg’s more embraced Saving Private Ryan, it makes a conscious choice to avoid traditional tropes and juxtapose war with philosophy and nature. Just shy of 20 years later, The Thin Red Line remains an item of affection for critics and audiences, and is arguably Malick’s least polarizing and most commonly beloved film.

1. The Tree of Life (2011)

Terrence Malick’s magnum opus The Tree of Life is a masterpiece. Though even this one can polarize the masses, the film stands out as an exceptional work and cements Malick’s status as one of the best filmmakers of all time.

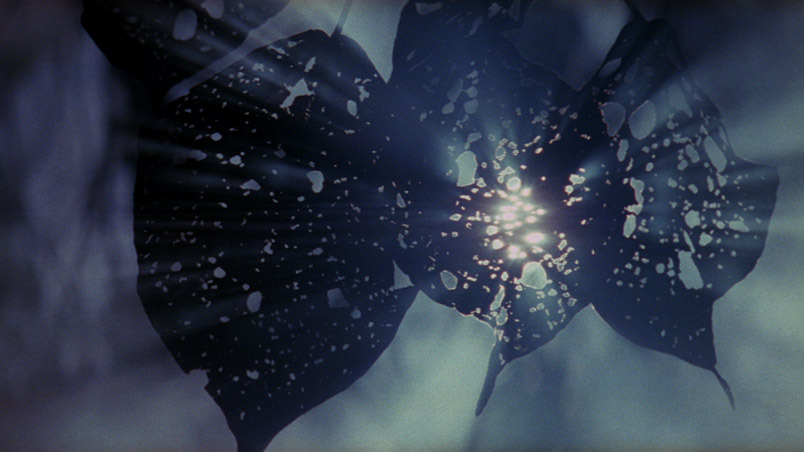

This seems like a given, but the film’s visual component is breathtaking. It’s some of Emanuel Lubezki’s best work, which is saying a lot – the use of natural light and a multitude of ground breaking techniques (including recreating wonders of the natural universe in a lab with lights, water, and dyes) make the film a visual beauty that stands above the rest of Malick’s exceptional imagery.

Moreover, Malick’s love of classical music is most evident in this film, filled with some of the best orchestral music in history. It is said that in the many years leading up to this passion project, Malick would jot down his ideas in a notebook that was filled with music he imagined accompanying the vague ideas that would one day form The Tree of Life.

The film brags a wonderful cast, including Brad Pitt, Jessica Chastain, and Sean Penn giving some of their lifetime best performances. A natural tearjerker, Chastain admits that after seeing the film once, she can’t bear to watch it again. Malick proves he’s a master of directing child actors, evoking memorable work from many, particularly Hunter McCracken.

Above all, the film stands out for its heavily layered philosophical tapestry. It beautifully conveys the notion that our understanding of existence and the universe is made possible by the telescope of family; it is one of the most memorable filmed meditations on existence and the meaning of life of all time. Tragically, the fragility of the central family in the film makes it virtually impossible for Jack O’Brien, played by McCracken and Sean Penn, to ever find a comfortable place in the universe or be at peace with himself.

About 30 minutes into the film, which is non-chronologically scattered all over the place, it is revealed that one of the children in the O’Brien family dies at a very young age. This trauma affects every member of the family in different ways, particularly damaging and exacerbating the character of Brad Pitt’s gordian father figure.

Leave it to Malick to force us to hate Mr. O’Brien’s abusive tendencies and yet be taken aback by his oneness with music when he sits at the piano, and feel a heartbreaking sympathy for the broken man.

The Tree of Life received a generally positive response, earning Terrence Malick the Palm D’Or at Cannes among other high honors. Always a Malick loyalist, Roger Ebert wrote that he considered adding it to his top 10 of all time (although it ultimately did not make it). The BBC’s poll of the 100 best films of the 21st century has it ranked number 7. It earned a score of 84% on Rotten Tomatoes, much better than most of his recent works.

One thing worth discussing is where the film fits within Malick’s two phases, which only seems appropriate given its musings on fitting within the universe. It almost serves as a bridge between the first and second phases – it feels like it could be part of the first very much because it’s one of Malick’s bests… but it’s bold use of non-chronological structure and Emmanuelle Lubezki’s breathtaking, naturalistic cinematography bears similarity to Malick’s phase 2. In many ways, The Tree of Life stands out on its own – so thematically rich and philosophically bold, it truly is one of a kind.

Author Bio: Ian Zigel lives in Miami, Florida. A filmmaker himself, Ian loves and appreciates film from around the world and of every decade.