5. Lawrence of Arabia (1962, David Lean)

Based on the life of the British military leader T. E. Lawrence

Possibly the most archetypical biographical film on this list, “Lawrence of Arabia” is simply the embodiment of an out-and-out perfect biographical film.

The film opens in 1935, the year of Lawrence’s fatal motorcycle accident. As the credits are shown on the screen, we see Lawrence (Peter O’Toole), in one long, static shot, shown from above, preparing for his fateful motorcycle ride.

The sequence ends with his death followed by the memorial service in his honor at the St Paul’s Cathedral. We see a reporter trying to gain insight into the life of the enigmatic military officer. He gets some vague answers but ultimately remains unsuccessful in his quest.

Thus, the film successfully establishes the mystery that is the life of T. E. Lawrence, before the story of his life has even begun. This also represents one of the many geniuses of “Lawrence of Arabia”, that by having the death of the protagonist right at the beginning, the film succeeds in eliminating the audience’s ability to predict the ending.

Since its release, the film continues to be beloved by audiences and critics alike. David Lean had previously made “Brief Encounter” and “The Bridge on the River Kwai” but it was “Lawrence of Arabia” that cemented his name as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time as it rightfully got nominated for ten Academy Awards of which it won seven.

In 1999, “Lawrence” was named the 3rd greatest British film of all time by the British Film Institute. In hindsight, it could just as easily have been named the greatest. Epic in scope, awesome in visuals, and stunning in its portrayal of the remarkable military leader, “Lawrence of Arabia” remains an absolute masterpiece.

4. The Color of Pomegranates (1969, Sergei Parajanov)

Based on the life of the medieval Armenian poet and troubadour Sayat Nova

Undeniably one of the greatest cinematic journeys you will ever experience, Sergei Parajanov’s “The Color of Pomegranates” seems to transcend the medium of cinema as Parajanov basically reinvents the way we approach the medium in less than two hours.

In the opening credits, the film boldly states that it doesn’t attempt to tell the life story of the famous poet, instead, it tries to “recreate the poet’s inner world through the trepidations of his soul, his passion and torments, widely utilizing the symbolism and allegories specific to the tradition of Sayat Nova.”

Yet no opening credits can prepare the film’s audience to the super-stylized world of “The Color of Pomegranates”. It is separated into seven chapters, from Childhood to Old Age, as it visually and poetically tries to depict the poet’s life. These seven chapters consist of several carefully composed tableaux and every single one of those seems to tell their own story in and of itself.

This is vital since there is barely any spoken dialogue in the film which allows the audience to focus entirely on each individual tableau. To describe the plot any further would be meaningless since the film isn’t about the plot – it simply defies explanation. The film should not be regarded as a simple, narrative movie as much as it should, as Martin Scorsese has suggested, be seen as “a timeless cinematic experience.”

Since the release of Buñuel’s “An Andalusian Dog”, cinema hadn’t discovered anything close to being as revolutionarily new and radically different in terms of stylistic awareness until “The Color of Pomegranates”. This is merely one of the many reasons for its importance, and as film critic Gilbert Adair argues, “no [film historian] who ignores The Color of Pomegranates can ever be taken seriously.”

3. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Based on the life of the famous French heroine Joan of Arc

In Carl Dreyer’s ”The Passion of Joan of Arc”, Renee Maria Falconetti delivers one of the most iconic, timeless and heartbreaking performances in all of silent cinema as she portrays the final hours of Joan of Arc’s life. The fact that Falconetti never made another movie only enhances her haunting performance.

”The Passion of Joan of Arc” tells the famous story of the French heroine Joan (Falconetti), who, after having lead several battles against the English during the Hundred Years’ War, has been captured and is about to stand trial.

Perhaps the most idiosyncratic of all silent films, “Joan of Arc” is filmed entirely in medium shots and close-ups, we don’t even clearly see the room the trial takes place in. By employing this unique style of filmmaking, Dreyer’s images seem to penetrate right through our soul, making the story seem timeless. There is no logical reason why his cinematic magic works, it simply does.

Since its release, “Joan of Arc” has made numerous appearances on various “greatest films of all time” lists and appeared five times on Sight & Sound magazine’s “top ten films” poll.

One of the many reasons, the film continues to be so popular could be that it transcends time and place, the film simply appears as “a historical document from an era in which the cinema didn’t exist,” as the French director Jean Cocteau famously stated, which is perhaps truer today than it was back then. “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is a major towering achievement and must be seen by anyone who would like to be considered as a serious film buff.

2. Andrei Rublev (1966, Andrei Tarkovsky)

Based on the life of the medieval Russian icon painter Andrei Rublev

Andrei Tarkovsky has now for a long time been recognized as the definitive embodiment of the art house director and his arguably greatest film, “Andrei Rublev,” the antithesis of the Hollywood biographical film, remains amongst the greatest art-house biopics ever made.

Loosely based on the life of the great iconographer, the film realistically depicts the bleak 15th-century Russia as we follow the almost Christ-like Andrei Rublev on his great journey through the beautifully filmed Russian landscape.

Dived into eight chapters, which can also be viewed as eight individual mini-stories, with a prologue and an epilogue loosely related to the rest of the plot, “Andrei Rublev” is more than three hours long, but to complain about the length of the film would be missing the point. It has been said that Tarkovsky’s films “uses length and depth to slow us down, to edge us out of the velocity of our lives, to enter a zone of reverie and meditation.”

In the film’s breathtaking climax, the screen bursts into color as we, in several extreme close-ups, see Rublev’s magnificent paintings, and now realize that his paintings are the sum of his epic journey.

The critic Steve Rose, who proclaimed “Andrei Rublev” to be “the best arthouse film of all time,” elaborates on this notion, “As the camera pores over the details […] we feel like we understand everything that’s gone into every brushstroke. We’re reminded of what beauty is. It is as close to transcendence as cinema gets.” To completely comprehend a film as complex as “Andrei Rublev” seems near impossible but that doesn’t mean that we can’t gaze at its aesthetic magnificence and poetic, visual grace.

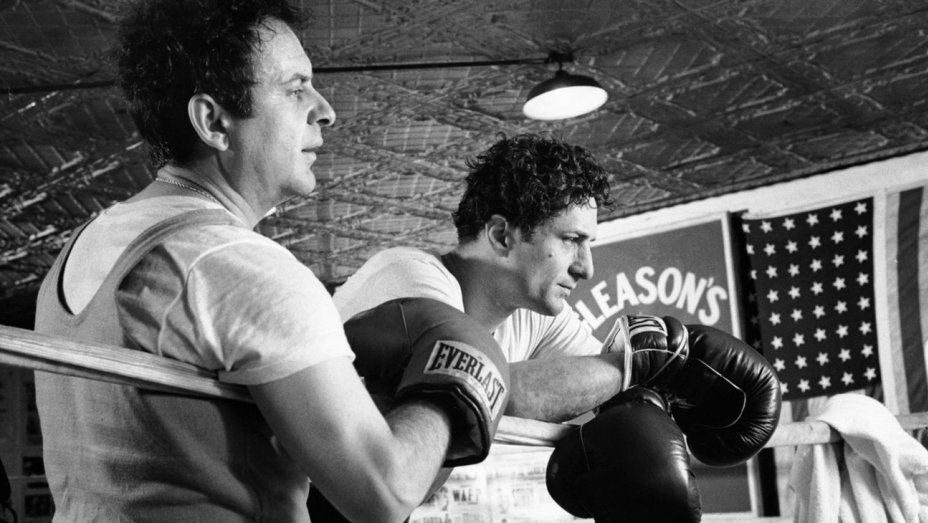

1. Raging Bull (1980, Martin Scorsese)

Based on the life of the former middleweight champion Jake LaMotta

It has been called “the greatest cinematic expression of the torture of jealousy–[Scorsese’s] Othello”, and is today considered one of the supreme masterpieces of world cinema. “Raging Bull” catapulted Martin Scorsese to the forefront of American directors and into the ranks of the world’s greatest filmmakers.

The film still to this day serves as a masterclass in direction, editing (cut by World-Class editor and long-time collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker) and black and white cinematography (shot by the phenomenal Michael Chapman, who also shot Taxi Driver) not to mention Robert De Niro, who arguably delivers not only the finest performance in his career but, perhaps, in the history of cinema.

The beginning of “Raging Bull” is one of the most iconic, beautiful, yet simplistic openings in American cinema, as we, in one long, unbroken shot, filmed in slow motion, see Jake (Robert De Niro) practicing inside the boxing ring to the sound of Pietro Mascagni’s beautiful Intermezzo Sinfonico. The scene that follows shows Jake at 42, overweight and out of shape, he’s rehearsing a nightclub monologue.

The film then cuts to a major boxing match, which takes place 23 years earlier when Jake was in his prime, young and successful. Already within the first two scenes, Scorsese has established a vast contrast between the young and the old Jake, and as in any good biographical film, we wonder, “how did he get there?” That is the question, the film tries to answer, but the film is of course much more than that.

The film knows that it is not the plot points, the audience finds interesting, but the lyrical spaces in between the plot points. That is why it has often accurately been said that “Raging Bull” isn’t really a film about boxing but about “a man’s jealousy about a woman, made painful by his own impotence, and expressed through violence.”

At the center of “Raging Bull” is the performance of Robert De Niro, who doesn’t simply play LaMotta, he becomes LaMotta. De Niro deservedly so won an Academy Award for his performance. Since Robert De Niro’s performance as Jake LaMotta, when he famously gained 60 pounds to play a bloated LaMotta late in life, method acting hasn’t ever been the same again. Opposite of De Niro is Joe Pesci, who plays Jake’s younger brother, the perfect counterpoint to De Niro’s performance. Their verbal battles become one of the many highlights of the film as it displays some of the best-written dialogue captured on film.

The film was nominated for eight Academy Awards but ended up losing Best Picture to “Ordinary People,” a film which most people barely remembers these days. Today, “Raging Bull” deservedly continues to rank amongst the greatest films of all time.

It is also very much appropriate that it is “Raging Bull” which tops this list since Scorsese could easily be considered for the role as the godfather of biographical films, as he has made more excellent biopics than any other director, dead or alive, and “Raging Bull” is most likely his best. It still remains, after almost 40 years, a truly superior work of cinema that is in a class by itself and continues to influence films made all over the world, “Raging Bull” is the most important biographical film ever made.

Honorable Mentions: Goodfellas by Martin Scorsese, Lola Montès by Max Ophüls, Bonnie and Clyde by Arthur Penn, Young Mr. Lincoln by John Ford, Dog Day Afternoon by Sidney Lumet, Edvard Munch by Peter Watkins, An Angel at My Table by Jane Campion, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser by Werner Herzog, Casino by Martin Scorsese and The Flowers of St. Francis by Roberto Rossellini.

Author Bio: Jonas Skov Pedersen is a Danish student and a passionate lover of film and if he isn’t watching or writing about cinema, he can most likely be found reading Russian literature from the nineteenth century or listening to the tunes of Bob Dylan. A list of his favorite films with detailed critical reviews can be found on IMDb (http://www.imdb.com/list/ls031367581/). He also writes articles and film reviews regularly, in Danish, for Alice (http://alicemag.dk/author/jonass/).