6. Dark City (Alex Proyas, 1998)

Hollywood seems to be the only reference for western mainstream cinema nowadays. All of the highest grossing, most viewed and most remembered movies by casual audiences seems to have gone out of a thirty mile wide area in Los Angeles.

However, it wasn’t always like this. In the early XX century, France and Germany also had strong Cinema Industries, especially due to the high protectionism of both governments. To quote two examples, France’s Gaumont Film Company and Germany Babelsberg Studio were competitor companies as wealthy and promising as the Warner Brothers or Paramount Pictures in that time.

After WWII, American filmmaking became the norm, with their French and German counterparts changing their main course to niche markets. As conventional audiences became accustomed to certain structures and visual styles set by Hollywood standards, most box-office successes to this day tend not to be all too revolutionary in aesthetic identity or plot.

Alex Proyas’ Dark City seems to defy this American standardization from within. Despite being produced by New Line cinema, the movie was made as if to turn away from the Hollywood tradition (aside from its special effects complementarity) in favor of a revival of German Expressionism.

It is as if the Golden Age of Babelsberg, employer of directors such as Robert Wiene and Fritz Lang, was revisited through the lenses of the cinematography of the turn of the century. CGI, contemporary make-up techniques and high definition cameras are used as modern counterparts to the methods old German artists took from the stage.

This motion picture takes place in a city in which there’s only night. Murdoch, an otherwise common dweller, is haunted by a past he cannot recall, while learning the true nature of his environment and of an organization called the Strangers, angelic/alien archons who rule the city and its inhabitants.

The city without day seems like a very ingenious resource to keep the movie dark; this way, the lights and shades can be omnipresent, the same way a black and white movie would be. The architecture itself pays homage to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927): state-of-the-art technology, angular and vertical buildings, with a dirty and grayish tint, and even an enormous, babel-like tower at its center.

Alex Proyas’ Dark City

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

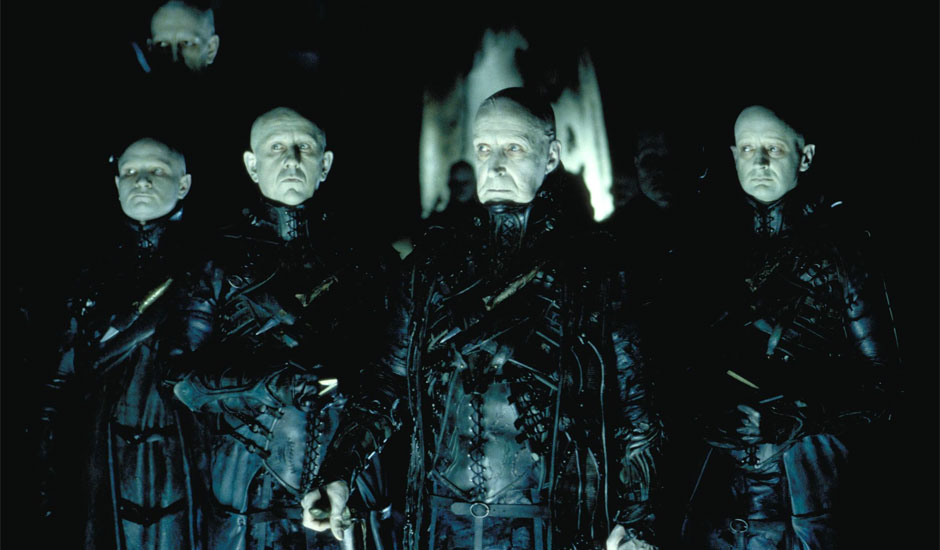

The strangers seem to evoke a lot of the noir vibe of the main gang in Lang’s M (1931). Fedora black hats, black coats and a somber attitude constitute their image.

Alex Proyas’ Dark City

Fritz Lang’s M

Their lair also references Metropolis; their dark building with a metal head in the center mimes Fredersen’s heart machine from the 1927 classic. Both are figures to be reverenced.

Alex Proyas’ Dark City

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

Dark City is a very interesting exercise in style and special effects, clearly influencing more well-known movies such as The Matrix and Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy.

7. The Last Combat (Luc Besson, 1983)

Despite being Luc Besson’s debut, made when he was only 24 years old, The Last Combat is a very substantial flick. Focusing on the primitive instincts and necessities of man, that arise when society collapses, the auteur shows a dystopic, post-apocalyptic setting with stimulating cinematography.

It becomes clear, from a film-theory point of view, that, for this flick, Besson let himself be influence by two cinematic schools: German Expressionism and Nouvelle Vague. The mixture of two such improbable styles of filmmaking resulted in a piece of great authenticity.

At first, we have the unusual choice of background. While most post-apocalyptic films revolve around nuclear disasters, global epidemics or other similar scientific explanations for the Earth’s demise, this French movie deal with a much more metaphysical approach: What if people had no more language?

With that groundwork being set, the director then builds the whole structure and general feel of the motion picture around it. At first, he makes it a silent film; since there is no language, the actors should work without any techniques of discourse, relying solely on body language and facial expression. Since the plot has a visceral concept from the beginning, it is only expected that the performers would have equally visceral enactments.

The next point, aside from sound, would be image. In order to experiment with light and shadow, while exploring the schools of both Fritz Lang and Jean-Luc Godard, Besson chose to make it black & white. This seems also to be a metalinguistic choice, in order to externalize, in the film itself, the bleakness and gray morals of a world without society.

In a more subtle manner, it’s possible to say the director uses both Nouvelle Vague editing and ethereal approach to plot and mixes it with the expressionist chiaroscuro visuals and silent film acting to deliver an original approach to the end of the world.

8. Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001)

“A woman trying to become a star in Hollywood, and at the same time finding herself becoming a detective and possibly going into a dangerous world.”

With this sentence, David Lynch pitched Mulholland Drive, a masterpiece of nonlinear storytelling, surrealistic landscaping and experimental filmmaking. The whole narrative is built as if it were a dream, without any concrete type of sequence of events, but with a lot of overlapping events.

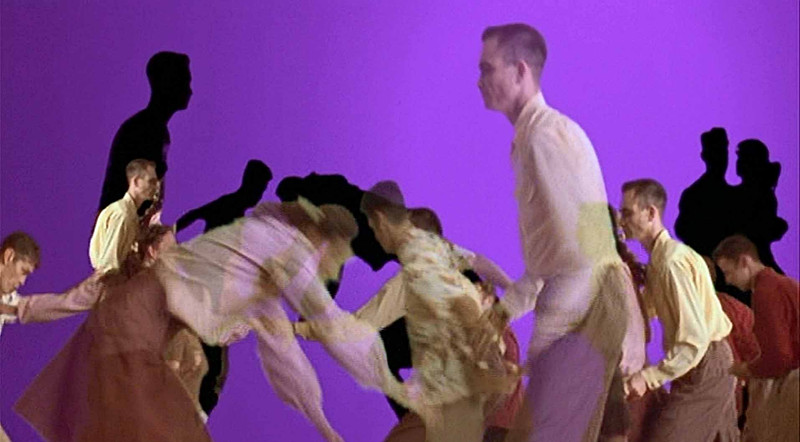

Lynch achieves the stylistic tone of his motion picture through a fusion of Expressionist and Surrealistic aesthetics. This fusion is perceived right at the opening scene, in which couples dance frantically to swing music in front of a purple scenario.

What give it an unsettling vibe, aside from the seemingly absurd concept of the scene, are the shadows; shades of couples dancing are an integral part of the plan, and it’s hard to tell to whom they belong. The scene ends when the saturated, close facial shot of the main character emerges on the screen, laughing. The movie then cuts to the dark streets of Los Angeles.

This scene uses the old treatment of shadows as an integral mise-en-scène, pioneered by the Babelsberg masters, but adds a pinch of Surrealism. The abrupt cut to a white, glowing character and then to a scene that is almost black invites the viewers to dwell in this world of bright lights, looming shadows and contrasting dark environments.

The zoomed close shots of actors conveying cathartic surges of emotions are also revisited throughout the film, especially in one of the final scenes, in which the two main actresses collapse to tears in a theater.

Lynch succeeds in this enterprise until the end of the movie. From the chase scenes, resembling old noir movies, to the climax in the bizarre Club Silencio, Lynch permeates every frame with, sometimes bleak, sometimes light, oneirism. This oscillation between nightmare and dream, light and shadow, identity and nature, are at the core of the expressionist experience.

9. The Cremator (Juraj Herz, 1968)

The Czechoslovak New Wave was a cinematic movie led by the avant-garde of Prague during the 60s. Despite not sharing a common aesthetic, structural or thematic line, motion pictures from this era ride the same progressive wave, bringing authenticity and artistic identity to an industry otherwise pinned down by socialist ideology. This ethos was very prolific, and has many examples of great depth and cinematic quality.

One key example is Juraj Herz’s black comedy “The Cremator”. Set in the 1930s Czechoslovakia, the plot follows Karl Kopfrkingl, a cremator who approaches his job with a spiritualistic point of view after getting in touch with a Tibetan book of the dead. He delves into fanaticism as he believes his burning of bodies eases the passage of the soul to the afterlife. As his country is annexed by the Nazis, the invaders begin using his talents for their holocaustic purposes.

The whole movie focuses on Kopfrkingl disturbed mind and descent into insanity. In order to visually architecture this character development, Herz built the narrative in a subjective way, styling it in a very expressionistic manner. This way, the viewer is progressively put in an uneasy position, not only by the turn of events, but also by the strong and bleak graphic content.

The cinematography is black and white, chock-full with deep focus, and rapid cuts and scene transitions.

The extreme close-ups used in the opening scene, in which caged animals are juxtaposed with images of Kopffrkingl and his family are a stylish and elegant approach to what is to come: a journey inside the mind of a madman.

10. Most of Tim Burton’s work

Burton is maybe the most mainstream director to clearly reference German Expressionism throughout his whole work. His depiction of Gotham in his Batman Returns (1992), his choice of style for the factory in Edward Scissorhands (1990) and the narrative use of shadows in Corpse Bride (2005) are clear examples (out of many, many more) of this filmmaker’s identification with the movement.

His references are clear to the point of naming a character in his Batman series Max Schreck, same as the German actor of Nosferatu (1922). Examples can be found in:

Figurine,

To the right: Edward Scissorhands; to the left, Cesare, from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

Scenarios,

To the right, Tim Burton’s Gotham City in Batman and, to the left, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

Even clear reenactment of scenes

To the right, Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride, and to the left, Murnau’s Faust

And many, many other instances.

Tim Burton’s work is a great way to get to know the forms and tropes of German Expressionism, in a usually playful and contemporary way. It contributes with the notion that artistic movements are not dated fashions, but points of view of art and life itself.

Author Bio: Lucas Guanaes is a film enthusiast from Brazil. When he’s not watching movies, he’s doing research in the international business area or playing with his four-piece band Bears Witness.