One of the most common accusations made against genre movies, or in fact any movie that isn’t either an arthouse favorite or Oscar bait, is that they’re “style over substance.” What critics mean when they use this expression is that the movie prioritizes its visuals over a perceived depth; films that prefer to dazzle the viewer with the virtues of their technical aspects than provoke thought on a societal or philosophical issue.

It goes without saying that any piece of art capable of initiating a discussion of any kind is admirable, but that doesn’t mean that films which purposefully lack a commentary or message are any less ambitious or worthy. In fact, it could be argued that, since cinema is a medium that concerns itself with storytelling through images, any movie that is able to be creative with the use of the cinematic language is cinema at its purest form.

To invoke an emotion simply with the use of sound and image is the true challenge of any and all filmmakers so, at the end of the day, many movies that carry the stigma of being style over substance may not be as profound as others, but they are just as much of an achievement, just a different way.

That is not to say that there aren’t movies that do get carried away with visuals and forget all the other important aspects of filmmaking, but there are several examples of movies that prove that, when done, style becomes the substance.

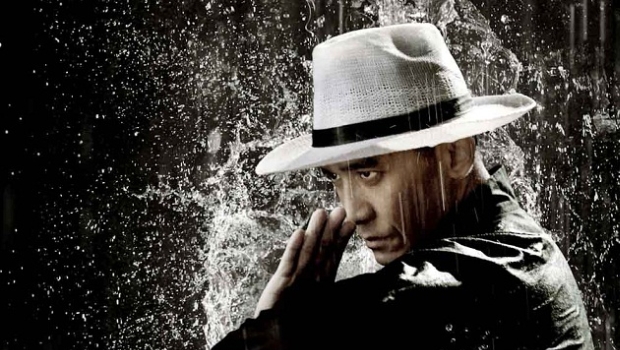

10. The Grandmaster

Martial arts movies are as old as cinema itself, a subgenre so rich and powerful it expanded way beyond its country of origin (China, where the wuxia is a cinematic institution), and influenced countless other filmmakers from all around the world, especially in the West, where it blended with other styles to create something entirely new (the most shining example of which is probably “The Matrix”).

But for a genre so expansive and traditional, there are remarkably few movies that really focus on the “arts” part of the name, films that substitute mere brute force for something more elegant, that demonstrate the immense level of skill required to land a punch. And that’s where Wong Kar-wai, one of the most sophisticated and celebrated directors alive, comes in.

“The Grandmaster,” his passion project that for many years got stuck in development hell, does have a meandering plotline and some underdeveloped characters, but it also features some of the most beautifully shot and choreographed fight scenes you’ll ever see. Wong and his editor William Chang are precise with every cut, making each single movement from the actors land with incredible power, highlighting the nuances of the choreography that plays more like a dance. In fact, the action scenes in “The Grandmaster” feel like a very complex ballet of violence, thanks to wonderful cinematography by Philippe Le Sourd (nominated for an Oscar), who films everything in a ethereal, almost dreamlike light.

“The Grandmaster” ultimately lacks the depth of Wong’s other films, but its style is so on point that there’s really no need for anything else.

9. Stoker

Fresh off the international success of his Vengeance Trilogy, Chan-wook Park’s first American movie, “Stoker,” was awaited by every cinephile on the block with amazing excitement. Perhaps that’s part of the reason why the movie landed with such mixed, lukewarm responses from both critics and Park’s own fans, who admired his brand of operatic violence and expected to see more of it here, but found a moody, slow and enigmatic movie instead.

It’s definitely a change of pace from his previous work; in “Stoker” there are no clever twists, no sudden bursts of blood or high, melodramatic emotional notes. But, at the same time, it’s very much Park’s vision, the clear work of an auteur with a style.

While the actual story doesn’t amount to much more than a more sinister retelling of Hitchcock’s “Shadow Of A Doubt,” the atmosphere created by Park with the help of ace cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung (who also lensed this year’s hit horror “It”) is something to marvel at: there are very few directors in the world that can conjure up imagery so evocative like Mia Wasikowska’s trip to the cellar, or the magnificent transition of Nicole Kidman’s hair to a field of wheat.

The aesthetic of “Stoker” is so intelligent and well thought out that it’s also worth noting the color scheme of the movie, which uses red and yellow in many different objects and ways throughout to symbolize the characters feelings or motivations and how they connect and change as the situations progresses.

Also featuring a fantastic score by the always great Clint Mansell, “Stoker” is not Park’s best, but it’s a triumph of style that deserves more praise.

8. Victoria

Since Alfonso Cuaron blew the collective minds of everyone with the virtuoso action sequences of his influential masterpiece “Children of Men,” tracking shots have become somewhat of a trend, a commodity even.

Cuaron wasn’t the first to use the technique (De Palma and Scorsese say hello), but the ferocity with which he put them to use revolutionised the way filmmakers thought the camera could be used, and now it’s become common, almost banal, for a director to use a tracking shot to show off or to infuse a scene with energy (like in this year’s “Atomic Blonde”). But even with tracking shots becoming less and less special, there’s nothing, absolutely nothing that compares to the insanity of “Victoria.”

It’s not the first time a movie is entirely made in one long, uninterrupted tracking shot: Alexander Sokurov did it with “Russian Ark,” and Cuaron’s friend Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu did it just a few years ago to Oscar-winning effect with “Birdman.” But what sets “Victoria” apart from these movies is that, unlike “Birdman,” there are no hidden cuts and, unlike “Russian Ark,” this is a fast-paced, kinetic intense action movie.

“Victoria” is a straight up genre affair about a group of friends that see their night get increasingly crazy as they become involved in a robbery, and the tracking shot makes what could already be a tense movie into something more. Told in real time, we follow these characters every second, uninterrupted, as the camera climbs into cars with them, goes up buildings with them, is chased by the police with them, travels across the city with them. It creates an intense empathy with their situation, as the viewer simply can’t let go.

It’s one of the most complex camera works ever put to film, and has to be seen to be believed.

7. Sin City

Made just before comic book movies became the driving force of the American film industry and the box office, “Sin City” is a unique example of how the two mediums can meld together to create something that is both obsessively faithful to the original material and completely, breathtakingly cinematic.

In fact, had it been it made today, “Sin City” would probably be hailed as a subversive entry in the already tired genre, like “Logan” and “Deadpool,” as it is drastically different from the Marvel formula the public has grown accustomed to. Not only is it vibrantingly violent and populated with nothing but morally bankrupt antiheroes, the aesthetic of the movie is an utterly distinct, beautiful beast.

Robert Rodriguez basically transposes the vivid, expressionist drawings of Frank Miller from the page to the screen, and so it would be easy to dismiss his work here as lazy or simply an imitation, but it’s actually harder than it looks. When doing an experiment such as this, there’s a risk that everything will become lifeless and bland, which is what happens, for example, to “Watchmen,” a movie that similarly tried to recreate the panels exactly and became just a parade of pretty images with no soul.

The opposite happens in “Sin City”: Rodriguez (who is also the DP in the movie) is able to capture the impressive visual beauty of Miller’s creation and infuse it with energy, maintaining the complex shadow and light lighting of the black and white and giving it a sense of irreality thanks to the extensive use of green screen, which fits that world perfectly.

6. House of Flying Daggers

This may be the second movie featuring the great Chinese actress Ziyi Zhang to appear on this list, but “House of Flying Daggers” is as different from “The Grandmaster” as “The Godfather” is from “Goodfellas.”

They are both, indeed, martial arts movies, but “House of Flying Daggers” is the only true representative of the wuxia genre, which concerns the exploits of master martial artists in ancient China. It’s a very long and prosperous genre that has given birth to many classics throughout decades, but what sets this film apart even in such crowded competition is the absolute feast of the senses presented by director Zhang Yimou.

The director is no stranger to the wuxia, and just three years before “Daggers,” he released the masterpiece “Hero,” but that movie cannot be accused of style over substance, as it touches upon a variety of themes and meanings. “House of Flying Daggers” is a little more thin on the thematic side, but that is absolutely fine, considering the visual splendor of every frame.

Yimou uses color here like in a Technicolor Powell and Pressburger musical, from the initial dance number filled with blue and pink, to the incredible bamboo forest with its resplandecente shade of green. And while the fight scenes in “The Grandmaster” are treated almost as a ballet, here the choreography prioritizes the impossible physics typical of the wuxia, and the result is a wonder to behold.

“House of Flying Daggers” may not be the best or most prestigious wuxia movie (those honors would probably go to “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” or “A Touch of Zen”), but it might be the most entertaining.