5. The Fall

The visuals are always a priority in the mind of any filmmaker when they sign up for a new movie; after all, images, more than dialogue or anything else, are the integral element that cinema is built upon. But while the vast majority of directors, even the most visually sophisticated ones, usually begin with a story and then figure out how to tell the narrative in the form of moving pictures, some have vivid visuals in their minds and then create a story simply as an excuse to show them. Such is the case of Tarsem Singh with “The Fall.”

There’s a plot somewhere in this movie, but it’s absolutely irrelevant. What truly matters is the quite simply unbelievable imagery the director and his DP Colin Watkinson are able to create. Singh is a very irregular director, with more misses than hits (“The Cell,” “Immortals,” “Mirror Mirror” and “Self/Less” is a less than impressive oeuvre), but even in his worst movies there’s a sense of dedication that breeds through the usually beautifully composed shots, and nothing compares to the sheer monumental effort of “The Fall.”

Shot over four years in some of the most exotic locations all across the world, “The Fall” almost dares the viewer to keep up with the gorgeous, magnificent, exhilarating visuals that never stop from beginning to end. Everything from the framing (the camera is always placed at the exact place it should be for the most aesthetic pleasure) to the blocking (the disposition of the actors across the shot is perfectly imagined to be the most cinematic as possible) is so absolutely on point that the movie, despite its lackluster plot, has a feeling of the old epics that Hollywood produced in the 50s and 60s.

“The Fall” is definitely not a perfect movie, and many may feel that the narrative is boring, but when a movie has even transitional shots more breathaking than most other films, it’s still worth a shot.

4. Femme Fatale

In the 70s, one of the most rich and ambitious periods of American cinema, a group of young outsiders formed a filmmaking unity that would be known as the Hollywood Brats. Those “brats” were none other than Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma. The first four names went on to have some of the most lauded and prestigious careers in the history of cinema, winning dozens of awards and praise, but De Palma was consistently dismissed because he preferred style over substance.

What they don’t understand is that for De Palma the substance is precisely the style. He has made several masterpieces and most of the time those movies had a preoccupation with something other than pure style, whether it’s a political commentary (like in “Blow Out”) or a character study (like “Scarface”). But he’s at his most pure when doing a mean and lean B movie and, of those, none is better than Femme Fatale.

When speaking of style over substance, most people think of movies that are visually stunning, which, of course, is part of it (as this list has shown so far). But stylization goes much further than that: it’s how creatively a filmmaker can use the cinematic tools available to create something dynamic and unique, even if they don’t necessarily serve the story. Most narratives could be told in a boring shot/reverse shot kind of way, but more ambitious directors can mold cinematic conventions, both visual and storytelling wise, to their convenience, and that’s where De Palma is a master.

In “Femme Fatale,” he uses practically every trick in his tool kit: slow motion, gorgeous split focus shots (one of his trademarks), split screens, tracking shots, point-of-view shots and Dutch angles, among many others. And even aside from that, De Palma is almost meta with this movie, playing with the conventions of genre, especially noir, and so he emulates the aesthetic of those movies without surrendering to it, taking what’s established and making it his own.

When it comes to being stylish with the camera, moving across the space swiftly and elegantly, nobody does it better than De Palma, and he never did it more prominently than in “Femme Fatale.”

3. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

The best video game movie ever made that just so happens not to be based on a video game, “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World” sees Edgar Wright, one of the most visually creative and resourceful filmmakers working today, get to play in the Hollywood pool for the first time, and you can see his happiness at the opportunity flow through the entire movie with a maniacal energy.

Coming from the success of the first two installments of his Cornetto Trilogy, Wright got a bigger budget and the free reign to transform Bryan Lee O’Malley’s graphic novel into a quirky, fast-paced and stunning movie.

The first thing to notice is the brilliant editing. Wright is known for how well edited his movies are, but here it’s on whole other level. Every cut is made with precision of a surgeon in a operation; the scene transitions are clever and always surprising, and the general pace of the movie is dictated masterfully by the quantity and velocity of the cuts (notice, for instance, how in Ramona and Scott’s first date the cuts become slower to highlight the awkwardness of it all).

Wright and cinematographer Bill Pope also play with the typical visuals of both comic books and video games and create a unique look for the movie that blends those different styles together into something cohesive. That makes “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World” a movie that can both have split panels like a comic, and colorful, exaggerated background graphics like in a game.

It’s an absolutely interesting and, most importantly, an infinitely fun and entertaining romp of a film, all thanks to the well crafted style that only Edgar Wright could achieve.

2. Suspiria

There are a lot of great genre movies that work precisely because of how well they utilize the conventions of said genre to their advantage, but a much rarer and difficult thing is a movie that transcends genre, a masterpiece so utterly unique that it becomes something all its own. Such is the case of “Suspiria.”

A giallo film made by one of the genre’s founders and main master, Dario Argento, “Suspiria,” like most giallo, has a very loose plot and it’s mostly concerned with the visuals of horror, with the emotional and psychological imagery that provokes a chill down the spine. And what unbelievable images they are; what Argento and his whole team achieve here is something that takes the basic core concepts of the genre and takes it into a whole other level entirely.

Production designer Giuseppe Bassan creates unforgettable geometrical rooms that defy arquitetural logic, which create a often disturbing, confounding and impressive look that contributes to the otherworldly atmosphere of the film.

But those sets wouldn’t have half the same power if they weren’t lensed by cinematographer Luciano Tovoli, who lights everything with one of the most expressive uses of color in the history of cinema. Every single frame is bathed by vivid red or pink or blue, intense and always present, creating not only a magnificent aesthetic but also a dreamlike quality that many strive for but few can achieve.

Featuring yet and incredible idiosyncratic and unsettling score by Italian rock band Goblin, “Suspiria” may be a bit meandering and its story may even sound goofy, but the sheer visual brilliance achieved here is simply unparalleled and a monument to behold.

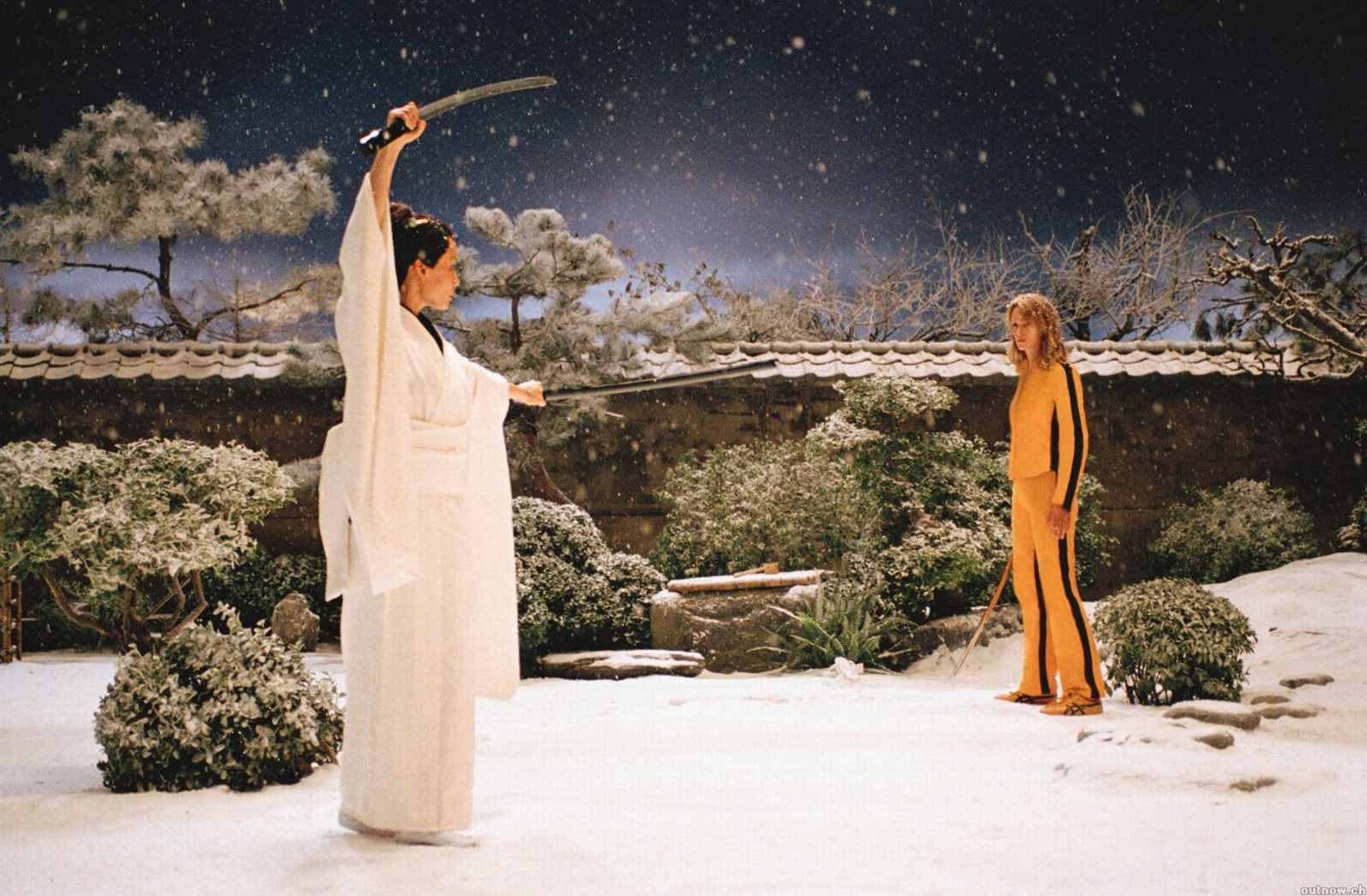

1. Kill Bill

“Why do we need such graphic violence?”

“Because it’s so much fun, Jen!”

Quentin Tarantino’s ironic, angry answer to a reporter’s questions about the exaggerated violence in his movies exemplifies perfectly his way of looking at cinema, his particular, controversial approach to storytelling, which achieved its peak of insanity in the epic “Kill Bill.”

Tarantino has always been a stylist above all, but the latter period of his career, considered highly visual, focuses more on social commentary and his earlier work, lacking the budget, is more dialogue driven to be truly considered a style over substance triumph. And then there’s “Kill Bill,” the movie right in the middle, that separates these phases and sees the director at his most unapologetic, violent and stylish.

A wild genre-bending movie, “Kill Bill” goes from a modern western to a samurai movie to a wuxia from one scene to the next. What could become a messy, inconsistent movie is salvaged by Tarantino’s absolute control over the tone; in “Kill Bill,” the real world is as far removed as it was in a galaxy far, far away. People don’t merely die; it’s mandatory that their limbs be decapitated and have an almost literal shower of blood flow from their bodies. Here, people don’t just walk, they move across any space with a calculated rhythm for maximum coolness. Everything is so exaggerated that it becomes a fantasy more than anything else, which allows Tarantino to actually make extreme violence fun to watch, basically having his cake and eating it too.

Aside from brilliantly handling the tone of the story, Tarantino also has immense fun stuffing the movie with visual references that range from Bruce Lee movies to Spaghetti Westerns, going all the way through Japanese cinema (most notably “Lady Snowblood”), 70’s crime movies and even Italian giallo, making the movie an amalgamation of everything that formed him as a cinephile. Tarantino is known for his references, but he’s never done it more openly and lovingly than here; this movie is a pure love letter to genre cinema of all kinds.

“Kill Bill” also is filled with visual and narrative cues and tricks that Tarantino takes from his masters: there are several split screens that would make Brian De Palma proud, a few tracking shots in the vein of early Scorsese and, of course, the nonlinear narrative that he himself popularized with “Pulp Fiction.”

As if all that wasn’t enough, the movie is also packed with Tarantino’s impeccable musical taste, which makes everything even more emotional and grandiose (the use of Ennio Morricone, his favorite composer, is particularly incredible). It is, at last, a masterpiece, that cemented Tarantino’s place as one of cinema’s most talented stylists.