5. Indian New Wave or Parallel Cinema (1952-1976)

The Indian New Wave movement coincided with what is called Parallel Cinema, a movement which provided alternate films to the mainstream affair. It can be argued that whilst Parallel Cinema continued on after the new wave waned that Parallel cinema was propelled into existence by the new wave.

Originating from West Bengal, the Indian New Wave was inspired by Italian Neorealism and aimed to provide narratives based in reality about contemporary issues. This provided an alternative to the dominant modes of escapism in India such as musicals and comedies AKA what would become Bollywood cinema.

The movement spanned many years, with its most popular period taking place in the 1970s. It established the careers of legendary filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, whose influence can still be felt today.

The Films: Do Bigha Zamin (1953), The Apu Trilogy (1955-59), Pyaasa (1957), Ankur (1974).

The Filmmakers: Ray, Ghatak, Bimal Ray, Shyam Benegal, Guru Dutt.

4. Japanese New Wave (1956-1976)

A trend becomes apparent when assessing this list: most new wave movements are born from outsiders and students of film. In most instances, new wave pioneers emerge outside the commercial system that dominates their national cinema. However, quite intriguingly, the Japanese New Wave emerged from the studio system.

The studios were willing to take a chance on filmmakers who aimed to challenge societal taboos and offer a filmic delicacy that Japanese audiences weren’t accustomed to. Rejecting Japanese cinematic traditions of historical narratives and archetypal characters, the films of this era often involved young rebels as protagonists, contained notions of sexual liberation, violent delinquency and addressed contemporary social issues.

The gamble by studios proved a failure as the films were heavily censored by the Japanese government and by the 1970s its popularity, and the support of studios (which were collapsing), began to wane. Its legacy, however, has shaped Japanese culture and media, with the kooky and rebellious spirit of the new wave becoming part of the DNA of modern Japanese cinema.

The Films: Bad Boys (1961), She and He (1963), Death By Hanging (1968), Eros Plus Massacre (1969).

The Filmmakers: Susumu Hani, Hiroshi Teshigahara, Nagisa Oshima, Seijun Suzuki.

3. New Hollywood (1967-1982)

As counter-culture’s popularity grew, civil unrest over the Vietnam War continued and the Hayes Code (a strict censorship law for films produced in Hollywood) was abolished, a new breed of films and filmmakers alike emerged to change American cinema forever.

Hollywood’s classic period made the industry a dominant force across the world. Studios produced an unprecedented amount of films each year and created a template for how films were made. However, with the Hayes Code looming over every production, there was always a limit to what could be shown and what stories could be told. The Hayes Code forbade nudity and explicit violence, as well as any narrative that glorified crime or allowed the criminal to get away with his crime. This often resulted in predictable, unrealistic narratives and an overly conservative cinema.

So with the Hayes Code gone and a new ideological force emerging in America, Hollywood was ready for a change. For the first time film directors were film school graduates, cinephiles who had studied in depth the films of classic Hollywood and the artistic cinema that was so popular in Europe. The subsequent films that emerged in the following period combined tropes from both styles of cinema; they were violent, sexually explicit, and uncomfortable to watch and focused heavily on the disturbed and the criminal. They paved the way for modern cinema and the blockbuster, inspiring generations to come.

The Films: Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Midnight Cowboy (1969), The Godfather (1974), Taxi Driver (1976).

The Filmmakers: Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, Steven Spielberg, Roman Polanski.

2. New German Cinema (1968-1982)

In the first half of the 20th century, German cinema was a powerhouse. Not only a roaring train of commercial success but the artistic movements within its cinema were some of the most impactful and inspirational there have ever been. Quite simply, popular Hollywood film genres such as horror and noir would not exist without German cinema.

However, post-World War Two German cinema struggled to continue the impressive work that had been produced before it. With the country quite literally divided (communist East and capitalist West), Germany’s cinema struggled to find an identity in this new era.

Then along came New German Cinema…

Spearheaded by a holy trinity of legendary directors in Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders and the taken-too-soon Rainer Werner Fassbinder, New German Cinema sought to re-imagine Germany’s cinematic landscape. The filmmakers of this new wave adopted the motto “Papa’s kino ist tot” (Papa’s cinema is dead) and produced many films during the period. These films can be characterized by their bizarre nature, beautiful aesthetic, colorful pallet, and narratives that delved into the human psyche and celebrated all that was odd and different.

They also served as a platform for reflection on a Germany divided politically and still recovering from its fascist past. The New German filmmakers turned their lenses on the German people, their regret, their idiosyncrasies and their transition into the modern world.

The Films: The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980).

The Filmmakers: Herzog, Wenders, Fassbinder, Margarethe von Trotta, Volker Schlöndorff.

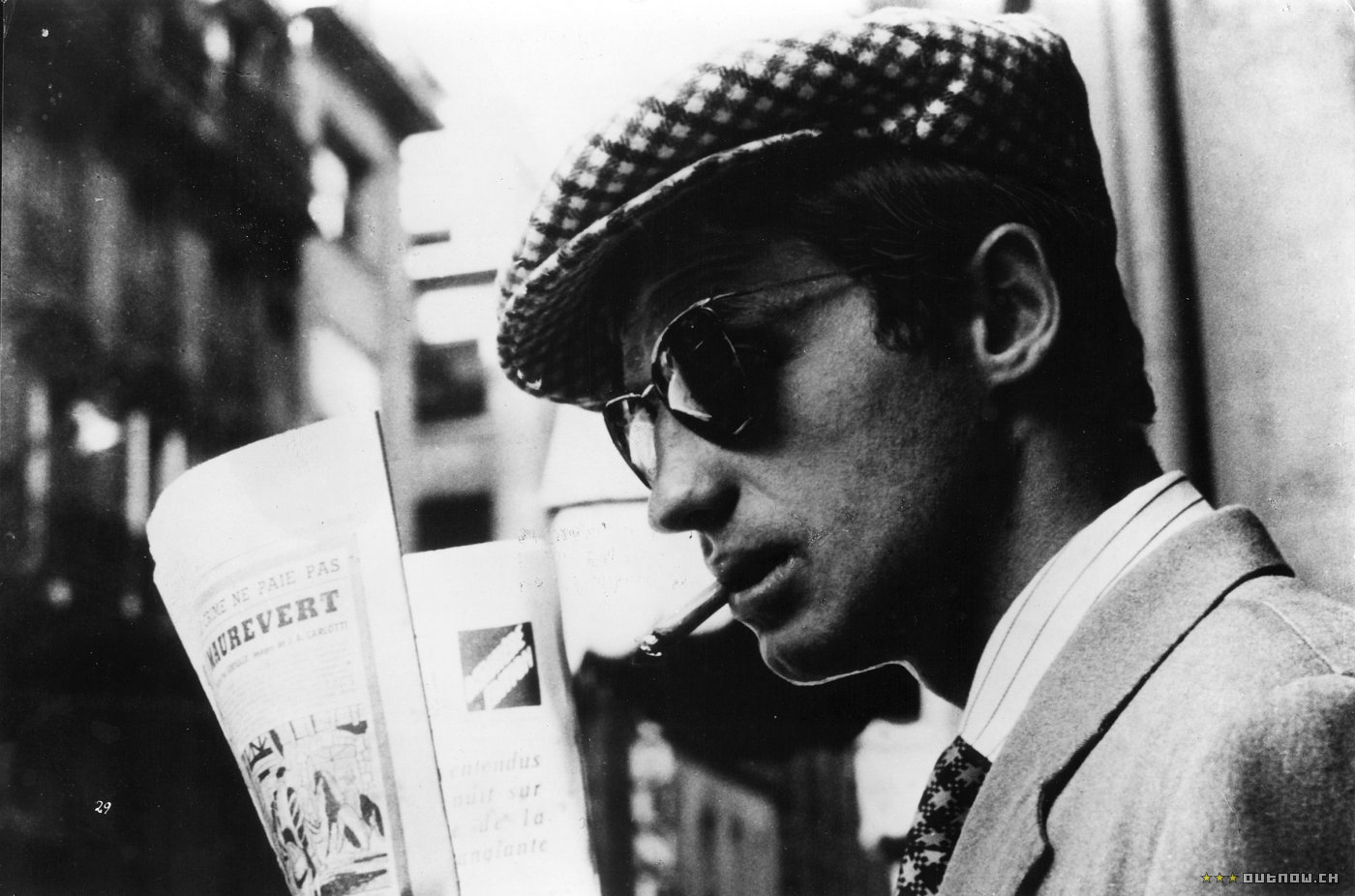

1. French New Wave (1958- 1973)

From its beginnings amongst the critics of Cahiers du Cinema, the French New Wave has defined a rebellious attitude that has served as a rejuvenating spirit for many other national cinemas. Celebrated film critic and theorist André Bazin mentored a generation of critics-turned-filmmakers that would challenge the conventions of cinema and radicalize the way in which films were made forever.

The French New Wave, or Nouvelle Vague, was defined by revolutionary filming and editing practices such as jump cuts, non-linear narratives, improvisation, location shooting and plots told from the perspective of the criminal underclass. Narratives that focused on social issues and engaged with philosophical concepts about the human condition displaced traditional French narratives, which were mostly period dramas.

Rejecting tradition and, in particular formalism, the French New Wave showcased the limitless possibilities of cinema and storytelling. It rejuvenated an industry that had grown stale and homogenized. Independent cinema owes everything to the group of rebellious French filmmakers that dared to start a cinematic revolution.

The Films: The 400 Blows (1959), Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), Breathless (1960), Cleo From 5 to 7 (1962).

The Filmmakers: Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut Agnès Varda, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol.

Author Bio: A movie lover from England with a passion for writing about cinema. Luke’s movie watching career has taken him from watching Jackie Chan movies on school nights to graduating with a masters degree in film studies.