8. It Follows – Disasterpeace

Richard Vreeland, better known as Disasterpeace, is an exemplary chiptune composer. His work in the video games “Fez” and “Hyper Lighter Drifter” makes his use of electronica in a way that is both revolutionary and classic at the same time. So it makes perfect sense for David Robert Mitchell to go for Vreeland when he made “It Follows”: a horror film with a terrifyingly inventive premise and style, but deeply rooted in the distilled view of cinema from the 80s and the 90s.

“It Follows” is the story of Jaime Height, who after having sex with her boyfriend Hugh for the first time finds out that an entity, with a, or more specifically any, human face will follow her and if it catches her, it will kill her and then begin following Hugh who passed on this curse to her. The premise could not be more bone chilling, and Vreeland’s hypnotic, translucent rumblings transport you to that world with an utterly graceful ease.

The music is something that constantly reminds you of the innocent video games from your childhood, and the gradual, insidious destruction of that innocence. It is vicious and unforgiving, much like most of the film, without giving any clear hints about the thematic relevance of its absurd angles, but only a muddied, almost inaccessible view of the darkness that awaits us just outside our bedroom door.

7. Under the Skin – Mica Levi

Mica Levi, in only two films and a handful of albums, has already established herself as one of the greatest composers of all time and not just among film composers. Her experimental, mysterious, clouded, elastic, frankly weird creations, seem to grow in stature with time and reflecting upon them is a delight all music enthusiasts should give themselves the opportunity to enjoy.

Her first film was “Under the Skin”, made by filmmaker Jonathan Glazer, whose “Birth” might possess the greatest film score ever composed. A science fiction about an unidentified woman who meanders around aimlessly, picking up men and sending them into a mysterious liquid void. As random and imperceptible the plot of Glazer’s impeccable film is, all its imagery comes to head when guided by Levi’s reverberating score.

She plays with all kinds of instruments and lets go of all rigidity and structure. All that remains is an inexplicably daring, effective, vital composition that along with allowing all of the film’s subjective plotlines to make sense, truly gets under your skin.

6. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo – Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross

Once described by Spin magazine as the “most vital artist in music”, Trent Reznor, aside from being the founder of the world-famous ‘Nine Inch Nails’, formed with Atticus Ross one of the greatest post-industrial bands of all time with “How to Destroy Angels”. Both artists have also collaborated on composing the scores to the David Fincher films “The Social Network”, “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” and “Gone Girl” – all three incredibly different, yet entirely in synch with Fincher’s singular, incisive vision that pierces into the darkness and finds the most disturbing truths and the most delectable styles to present them in.

There is a comfort in Fincher’s work that is never afforded in films of lesser directors. Its polished, but unpretentious; bleak, but sleekly designed; provides commentary, but is never unsubtle. That comfort is never more evident than in “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo”, Fincher’s sometimes flawed, but always entertaining adaptation of Steig Larrson’s bestseller.

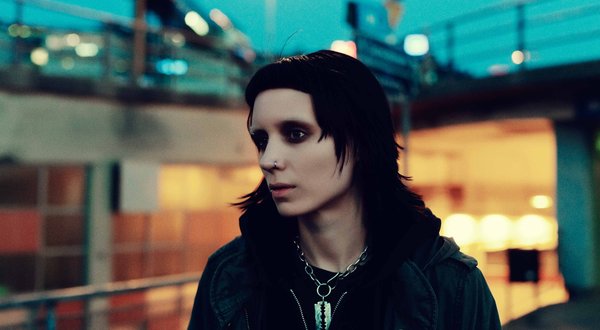

Reznor and Ross exploit that sense of comfort and use their funky, impressionistic notes to let the discomfort creep from every corner. It is as eccentric as the hairstyle of the film’s protagonist and as intense as the observing, assessing gaze of Rooney Mara. It underlines her pitch-perfect performance with a dazzling ease and an astonishingly sharp perception. It hides within it the film’s most rewarding secrets. All you need to do is listen carefully.

5. Sicario – Jóhann Jóhannsson

Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson has established himself in the last few years as a complete oddity. He has been releasing solo albums for years, but he received international acclaim, along with a Golden Globe win and an Oscar nomination, for his saccharine, subtle, swooning, quietly chirping score for James Marsh’s “The Theory of Everything”. He has subsequently partnered with Denis Villeneuve on two fantastic, mainstream, full-bodied artistic experiences with a female lead in the forms of “Sicario” and “Arrival”.

And in the former, he practically broke new ground with the way a score could exploit a terrific sound design. The film is centered on Kate Macer, an FBI agent, who begins to question the specifics and the ethical boundaries of her job when she partakes in a muddied, illegal operation whose aim initially seems to be to apprehend the lieutenant of a cartel called Manuel Diaz, but turns out to be to eliminate a cartel leader named Alarcón – which is eventually carried out by the dubious Alejandro, who is described only as an associate to the FBI.

Sicario is a riveting film, where real dangers await real people and could have real consequences. It never takes itself too seriously, though, but still has the resounding, booming intelligence in its voice, derived from the dread-inducing score by Jóhannsson. It looms large over the film, repeating its manic tranquil with alarmingly fresh insight every few moments. It underlines how deep the darkness the stark imagery of the film runs, and accentuates it at every turn.

4. Carol – Carter Burwell

The name Carter Burwell can never be pinned down to just one tag. Some remember his iconic, indelible score for the Coen Brothers’ “Fargo”, deftly following Frances McDormand’s perfect performance as it made us realize the dearth of honesty in our world.

Some remember his compositions for the Spike Jonze/ Charlie Kaufman films “Being John Malkovich” and “Adaptation” as well his unique, poignant score for Kaufman’s “Anomalisa”. Some may even know of him only from his work on the first “Twilight” installment. But Burwell has been one of the most versatile composers in film, the depth and range of work far too huge in magnitude for his underrated status.

Although he has worked with critics’ darling Todd Haynes on three separate occasions, his masterful, humbly romantic work in his 2015 film “Carol” launched him into another league. About two women – one engaged in a custody battle with her ex-husband and one a shop girl not in awareness of her true desires – who fall in love with each other, “Carol” is the frosty, unnaturally subtle, and perhaps the only near-perfect realization of what it feels to fall in love.

With Burwell’s uncanny, seductive use of various archaic instruments very sensitively informs us of the women’s most intimate feelings, because in Haynes’ honest vision and as played by two of the greatest actors of our generation, Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara, they rarely do so themselves.

The score tells us, in no uncertain and yet beautifully ambiguous terms, that to them, what they share is beyond the understanding of the people who surround them. They don’t have words to describe these emotions, and so they communicate mostly is looks and silent pauses, where Burwell’s hard-hitting, dizzyingly sincere music comes into play, leaving us crestfallen.

3. Gravity – Steven Price

Having worked as a member of the music departments of “The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers”, “The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King”, “Batman Begins”, “I’m Not There” and “Scott Pilgrim v. The World”, Steven Price was set to be a monumental presence in the film composer community. After proving his metal with the score for Edgar Wright’s “The World’s End”, he composed something so radically different from anything that he had ever been a part of before that he ended up winning the Oscar for a score that is rather unconventional, and most certainly not the kind the Academy usually goes for.

When you work with a filmmaker like Alfonso Caurón, there is a desire to go beyond the usual, the tested, to something much more human, and simultaneously possess a tangible mystery. Even John Williams did his career-best work in the third Harry Potter film when Caurón was at the helm. His singular vision for “Gravity” though has few parallels and the same could be said for Price’s slow burning, magnificently moving score.

Setting the landscape for a film that is almost set entirely in space is a difficult job. The experience must make you feel out of place, but should never be obvious, let alone discomforting. Price’s score builds to incredible crescendos, but it truly shines in the quietest of moments. It adds such delectable layers to Sandra Bullock’s performance that, like in the case of “All is Lost”, her incredibly expressive face begins to communicate so many things at once. Not all could be recounted, but they are felt and inhabited, nonetheless.

2. Jackie – Mica Levi

There is a reason Mica Levi is the only composer to have two scores featured on this list. Maybe it is because of how valuably different her work is from every other composer. Maybe it is because in the small amount of time we have known her and her compositions, she has crossed boundaries we never even knew existed. After making her presence known with “Under the Skin”, Levi outdid herself with her operatic, insanely all-consuming score to Pablo Larraín’s “Jackie”.

“Jackie” is the first work of art to have the former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy as a subject and tackle it from the inside out. For a film about someone whose persona was and whose legacy is so large, “Jackie” is astonishingly small. It doesn’t aim to deconstruct or invade the privacy of its protagonist, but using her, reflect upon how history is erected, how legacies are built and how vivid our connection to it is, all the while focusing on the few days following John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

Levi was not given the film as a finished product to provide the score to. She was asked to compose material and send it to the post-production team. Arising out of this unusual creative process, which significantly altered the way the film is edited, is a rousing, complex, unimpeachably beautiful, beast of a score that is frankly unlike anything anyone has ever done in film composition.

It moves at a random, absurd pace, skillfully painting an awe-striking portrait of Jackie, and whenever it rises in an unearthly crescendo and the impact of the film’s urgency dawns on us, you can’t help but think what Salieri says in Miloš Forman’s “Amadeus” about a composition by Mozart, “This is the voice of God.”

1. The Master – Jonny Greenwood

If Mica Levi’s score for “Jackie” is reminiscent of the unearthliness of Mozart, Jonny Greenwood’s score for Paul Thomas Anderson’s masterpiece sits atop this list for owning its earthliness with intellect, dried wit and sublime insight.

Whatever we might make of Anderson’s enigmatic film, tightly wound, yet as sovereign an exercise as the boundless ocean it so memorably captures, Greenwood’s score makes something instantly clear: nothing about this is untrue, and you have no choice but to believe its peculiar, telling undertones.

“The Master” is about an uncivilized, deranged man who returns from the war in 1950, and wanders around with no purpose or associations. He stumbles upon a boat where a mysterious cult leader who fashions himself as “the master” is on a voyage with his family and followers.

He soon learns about the man’s beliefs and teachings and begins to forge a dangerous, volatile friendship with him. He never fully buys into the master’s ideology, but both soon become inseparable, one, though as free as an animal, cannot seem to live without being in someone else’s reign, and the other cannot without being his master.

Greenwood’s decidedly unsentimental, richly complex score understands the film’s temperament absolutely and never wavers in detailing it with a mind-numbing precision. It is as luscious as the film’s 70mm cinematography, as resolutely irresolute as the miraculous performances and as irreproachable as Anderson’s unrivalled filmmaking.

It is the answer to all the questions the film raises, but even as it bellows with coldly methodical emotion, it never explains anything, leaving us more deeply entangled in our own musings: perfectly embodying the purpose of a film score.