When we look at things long and close enough, we will realize that they are way more complex than they seemed at first. Looking carefully into our lives, we start to identify contradictions and unexplainable events that make our experience as humans richer and more compelling. Out of all the small experiences, feelings, and emotions that populate our lives, pleasure and pain are likely the most important pair. They are the base of our actions in the world.

We strive for pleasure and do whatever we can to avoid suffering. In the nature of our own enjoyment and its opposite, our obsessions and fears are born and nurtured. But what happens when those two extremes collide? What happens when they are somehow intertwined, and we find ourselves feeling inexplicably ecstatic at the sight of pain, destruction, and cruelty?

Pleasure is in relation with one’s own body; it’s a sort of declaration of identity. We each have our own maps and paths and we walk through them in very peculiar ways. The very particular configuration of the things that allow us to experience gratification defines our relationship with ourselves and with others. And maybe at the heart of what we call love is a desire to find somebody whose pleasures are compatible with ours.

It knows no rules or standards, and it’s beyond good and evil, so the several rules of social behavior that have been set by the various human civilizations throughout history have always worked as a way to suppress the dark side of it. Those rules attempt to impose a moral code, resulting in repressed impulses that, confined in our psychic backwaters, develop into something even darker and more twisted.

Keeping in mind how the things we come to enjoy are testimonies of our inalienable individuality, I have compiled a selection of 15 films that explore the relationship between people and their pleasure, the dark places it can take them when it overrides the rational will, and how damaging it can be – for us and for others – when self-indulgence and exaggerated hedonism take control of our decisions.

1. Irreversible (Gaspar Noé, 2003)

The first moments of Gaspar Noé’s “Irreversible” are shocking, violent, and vomit inducing, while the last ones are tender, sweet, and loving. This is a film that explores an entire emotional spectrum, and it does so in quite a deft manner. We see a transition from gruesome, nausea-inducing violence to the sweet tenderness of two young lovers. Love and hate. Pain and pleasure. Life and death. Eros and Thanatos. They all collide in this film.

Masterfully maneuvered, the camera flies from one place to another, showing us in reverse the depressing tale of Alex (Monica Bellucci) and Marcus (Vincent Cassel), a couple whose lives are drastically damaged when she is brutally raped in an underpass in Paris. Marcus then goes on a rampage to find the guy who did it to take vengeance.

The film presents us with two kinds of sexual intercourse and their consequences. On one hand, there’s the sex inspired by love; the one that creates and re-affirms life, an exclamation of mutual understanding in which the attraction and affection felt towards that loved one, and the pleasure of being together, culminate in climax.

On the other side, we have the sex inspired by hate and destructive impulses, sex that is rather a fight to demonstrate who is the strongest, who can inflict the most pain, who holds the greater power. It is a kind of sex that is a physical disruption, where the will of the other is eradicated, and where pleasure is a narcissistic tool of destruction. It is a ritual for death and annihilation.

2. Moebius (Kim Ki-duk, 2013)

“Moebius” is a complicated experience that raises questions about the relationship between sexual gratification and the body. After being cheated on several times by her husband, a woman decides to take vengeance by tearing off his penis with a knife. When she fails to do that, she storms into her teenage son’s room and punishes him instead. She then runs away from the house, leaving the father and the son to deal with the suffering and confusion on their own.

From this point on, the film revolves around the search for pleasure. The father suffers from the fact that his beloved son won’t be able to enjoy the carnal satisfaction of sex, and he begins to search for procedures that would allow him to transplant his penis into the son’s body.

The film aims to explore the intricacies of physical pleasure and sexual gratification. When the son is rendered unable to have sex, he is forced to search for other methods of satisfaction. From the recommendation of his father, he starts rubbing a rock against the bare skin of his feet, damaging them pretty badly, but giving him a huge orgasmic wave of pleasure that is contrasted with a devouring pain that takes place after the orgasm wears off.

The film is told in a completely visual manner, emphasizing on the visual language of its performers. The phenomenology of the body is carefully examined, and we see it here as the center of our human experience, but it is portrayed as something that can easily be changed, transformed, and adapted, perhaps as a sort of toy with interchangeable pieces.

3. In The Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Ôshima, 1977)

In “In The Realm of the Senses”, we witness the fate of Sada Abe and Kichizo Ishida, a couple having an affair who are sucked completely by the abyss of lust and desire. By his way of telling this story (based on something that actually happened), director Nagisa Ôshima tears apart many of the taboos around the depiction of sex in cinema. His method to bypass obscenity is to show us genitals as frequently as possible, which resulted in the film being banned from Japan for several years.

What we see in the film is a couple that gives themselves completely to the exercise of their own pleasure. The images are populated by a strong and unconstrained sexual force that drives the characters towards blissful dementia. The social rules of what is acceptable are thwarted, and both lovers find in each other everything they need from life.

Obsession quickly sets in, as they become physically ill when they are away from each other, so their search and exploration of the body becomes an almost metaphysical quest that takes them to the breaking point after which everything dissolves and disappears.

4. The Piano Teacher (Michael Haneke, 2001)

Morale, expectatives (whether it be social, familial, or personal), and the construction of ourselves are a few of the factors that come to define our reaction toward sexual gratification. Here, Isabelle Huppert plays Erika Kohut, a pianist who lives with her mother despite being an adult, and who performs as a piano teacher at a prestigious music conservatory.

At a recital she meets a young, enthusiastic engineering student who falls in love with her when he attends her performance. She comes across as cold and authoritative, but he perseveres, taking Erika out of her comfort zone into a world of feelings she can’t quite control. Her repressed sexuality melts in an explosive manner once she finally decides to lose some of her iron-fisted control.

5. Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

“Blue Velvet” is a dark, twisted nightmare and a tango of sexual intrigue. It is a search for answers, a descent into unseen evil, an exploration of the unexplainable dark spots of pleasure. Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle Maclachlan) is a young man who gets involved with a singer named Dorothy Vallens, whose husband and son were kidnapped by an insane and extremely dangerous gangster named Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), and goes on to do whatever he can to help her.

Sexuality is presented to us as an expression of our identity, emphasizing the way each of the character’s’ personality through their erotic behaviors. While Jeffrey reacts with fear and commotion to his first sexual encounter with Dorothy, after a while he allows all his repressed impulses to fully emerge.

Dorothy is rather dominative, demanding to have pain inflicted on her and to be hit during sex, and Frank is furious and violent, with a disturbing fetishist enjoyment of sex through which we can assume a very unhappy and emotionally complicated childhood.

6. Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

James Woods plays Max Renn, a TV programmer for a small cable channel that specializes in violent and erotic content. Always on the lookout for new experiences for his viewers, he gets a satellite pirate to track an interesting piece of entertainment called ‘Videodrome’, in which a person, always a different one, is tortured by two masked men.

In an interview with radio host Nicki Brand (played by Debbie Harry) and Dr. Brian O’Blivion that touches upon very interesting philosophical points in the phenomenology of TV, of the dichotomy between reality and its representation, Renn justifies the extreme violence broadcasted on his channel by explaining it as a cathartic need for society.

According to him, if people can find the enjoyment and pleasure of violence through TV, they won’t feel the need to take their destructive impulses into their daily lives.

Among the many themes and subjects of the film, the addiction to entertainment stands out. In the film, the shelters for the homeless and poor don’t provide food or safe haven, but rather they are each assigned a TV that works as a sort of neurological methadone. The projection of our desires in TV is portrayed as a dangerous weapon that can possess us if we aren’t careful enough.

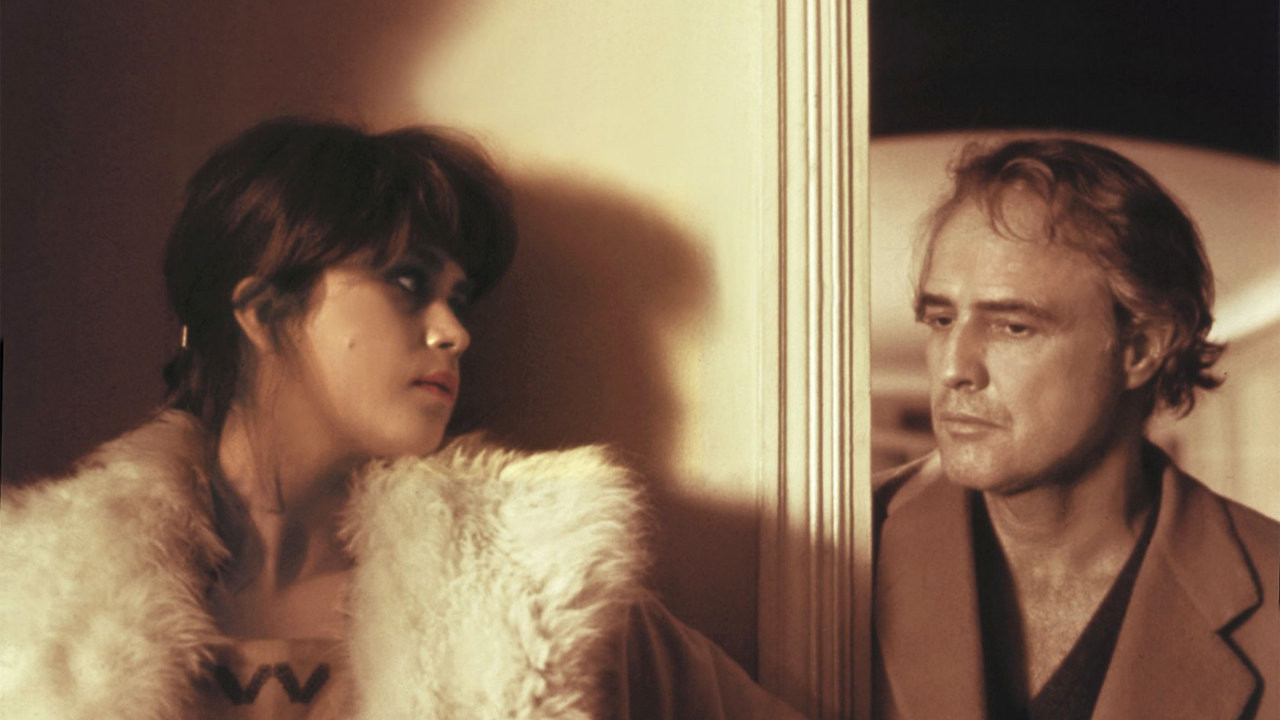

7. Last Tango in Paris (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1973)

Despite being stained by a gratuitous rape scene, it is still an engaging film that reveals the nature of intimacy, desire, and self-deception. Marlon Brando stars as Paul, a depressed American whose wife just committed suicide.

Searching for a new place to live, he stumbles upon Jeanne, played by Maria Schneider, a young woman who is on the verge of marriage, and almost immediately, they begin a very carnal relationship. They meet in the apartment, they have sex, but he never allows the relationship to go anywhere else, maintaining that everything remain anonymous and idealized.

Amongst the main themes of Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris”, we can find loneliness, grief, alienation, and how we canalize all those feelings through the body. The film begins with a couple of overwhelming representations of a man and a woman, and paintings by Irish figurative painter Francis Bacon that portray the human body as something twisted, malleable, a victim of pain and pleasure by equal measure. The body is sentient meat, without definition or identity.