8. Saló (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975)

“Saló” is probably the most well-known film directed by polemic auteur Pier Paolo Pasolini. Adapting a novel from the equally scandalous Marquis de Sade, it tells the story of four prominent political and religious figures who get together and kidnap nine adolescent boys and girls to subject them to sexual abuse and torture over 120 days. The fact that the film is set during World War II adds an important political dimension to an otherwise pointless and gruesome depiction of sexual violence.

The film is disgusting and painful to watch, but it is strong. Its extreme violence and masochistic imagery paint the picture of four deeply disturbed and evil individuals. While we, as spectators, feel nauseated and attacked by the constant physical humiliations the teenagers have to endure, they as perpetrators are getting just what they want. Once again, we witness pleasure as an assertion of control and power.

9. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Terry Gilliam, 1998)

Johnny Depp, Benicio Del Toro, a drug-fueled trip to Las Vegas, and constant hallucinogenic nightmares – that’s Terry Gilliam’s “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas”. Depp plays Raoul Duke, or rather legendary journalist Hunter S. Thompson, and Del Toro is Dr. Gonzo, his lawyer. Together they undertake a trip to Las Vegas to cover a race in the desert.

The film is a crazed marathon toward stimulation. It depicts the disappointment that followed the hippie culture of the 1960s, and more specifically, the drug culture and the belief that through psychedelics we would be able to find illumination and spiritual evolution. After the self-indulgence and the sexual hedonism of the 60s, what is left is a sour taste in our mouths and one nightmare after another on a path that leads to nowhere.

10. Nymphomaniac (Lars von Trier, 2013)

As one of von Trier’s most polemic films to date, “Nymphomaniac” stands as the tale of a woman who can never get enough from the world. Played by Charlotte Gainsbourg, Joe tells her story of sexual explorations as a series of flashbacks that outline her personality as radical, extremist, and never satisfied.

With a runtime of more than four hours in its uncut version, the film begins when a man named Seligman finds Joe and gives her shelter, and the story develops as she describes her life through a series of chapters. The film has several branching points; von Trier allows himself to talk about fishing, the Fibonacci sequence, and polyphony in Bach’s music, and somehow all those didactic intermissions in the plot help us gain a better and deeper understanding of Joe’s feelings and actions.

What drives the film is a sense of sublimated sexual energy. Sex is shown as a way of manipulation, as a way to get through life, as a way to integrate the body into the world and to understand what weakness and strength really are. A key element to life’s understanding.

11. Shame (Steve McQueen, 2012)

Probably the best film by Steve McQueen to date, “Shame” tells the stark and cold story of Brandon, a sexually obsessed man personified by Michael Fassbender who is forced out of his controlled environment by the arrival of his younger sister Sissy, played by Carey Mulligan.

Brandon has built around himself an environment in which he can exercise his addiction to sex without having to get involved in any kind of emotional intimacy. At its heart, what we have in front of us is the story of a wounded man who is a victim of the modern world’s lack of real feelings. Sex becomes then a sort of shell, a distraction used to bypass the pain and the loneliness to numb ourselves by the stimulation of the senses.

12. Funny Games (Michael Haneke, 1997)

Michael Haneke’s “Funny Games” is a critique of televised entertainment and its constant depiction of violence. A family – father, mother, and son – are held as hostages in their vacation cabin, and are forced into a spiral of senseless, unjustified, and undeserved cruelty.

By translating the values and actions we find likeable and enjoyable in the media into the real world, Haneke attempts to make us question the things we find funny and engaging, and how those things might reveal an unseen lack of empathy in us.

The film challenges the passivity of TV consumption and makes his characters have to deal firsthand with the spectacle of violence and abuse that manages to pass as entertainment in the media. While its critique of violence might come across as moralistic and self-righteous, it still raises a couple of questions that might reveal unexpected truths in the viewers.

13. Requiem for a Dream (Darren Aronofsky, 2000)

“Requiem for a Dream” is a heartbreaking film. Jared Leto, Jennifer Connelly, Marlon Wayans, and Ellen Burstyn star in this sad, depressive, and pessimistic experience that makes us witness the downward spiral of four drug addicts and their gradual loss of dignity, love, and hope.

Aronofsky’s films often explore the darker sides of the human condition. Depression, dementia, anxiety, and fear can all be found in his films. In “Requiem for a Dream”, we see drug addiction and how soul-crushing it can be.

The dionysiac escape from reality that drugs can bring when used recreationally is turned into the end of the world for our four protagonists in no time. Drugs are merciless and resentful; they eat you up and leave you with nothing. Yet their power of attraction is unparalleled, and that’s just what we see in this film.

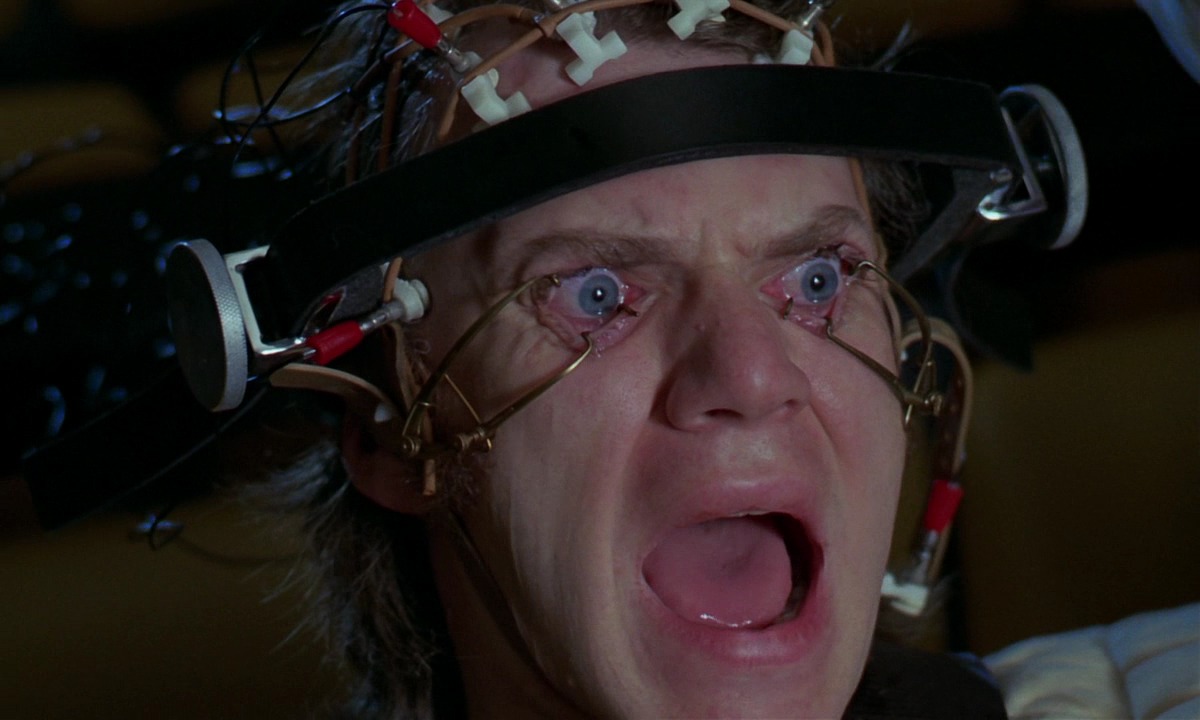

14. A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

“Being the adventures of a young man whose principal interests are rape, ultra-violence and Beethoven” is the text that accompanies the poster for this 1971 film. Stanley Kubrick adapted this film from the novel by Anthony Burgess in which Alex DeLarge, the leader of a gang, indulges in pleasures that are forbidden by society.

The excess and debauchery in which Alex allows himself to indulge are presented to us in an almost Nietzschean way. He and his droogs (or friends, in the film’s slang) do whatever they want; they beat people up, they steal, they take drugs, they rape and murder.

Aside from the moral and existential commentaries made in the film, we can see in Alex a person who has been neglected by society since his early childhood. He is a consequence of the environment in which he grew. Being deprived from love, he had to learn to find enjoyment and glee in pain and suffering.

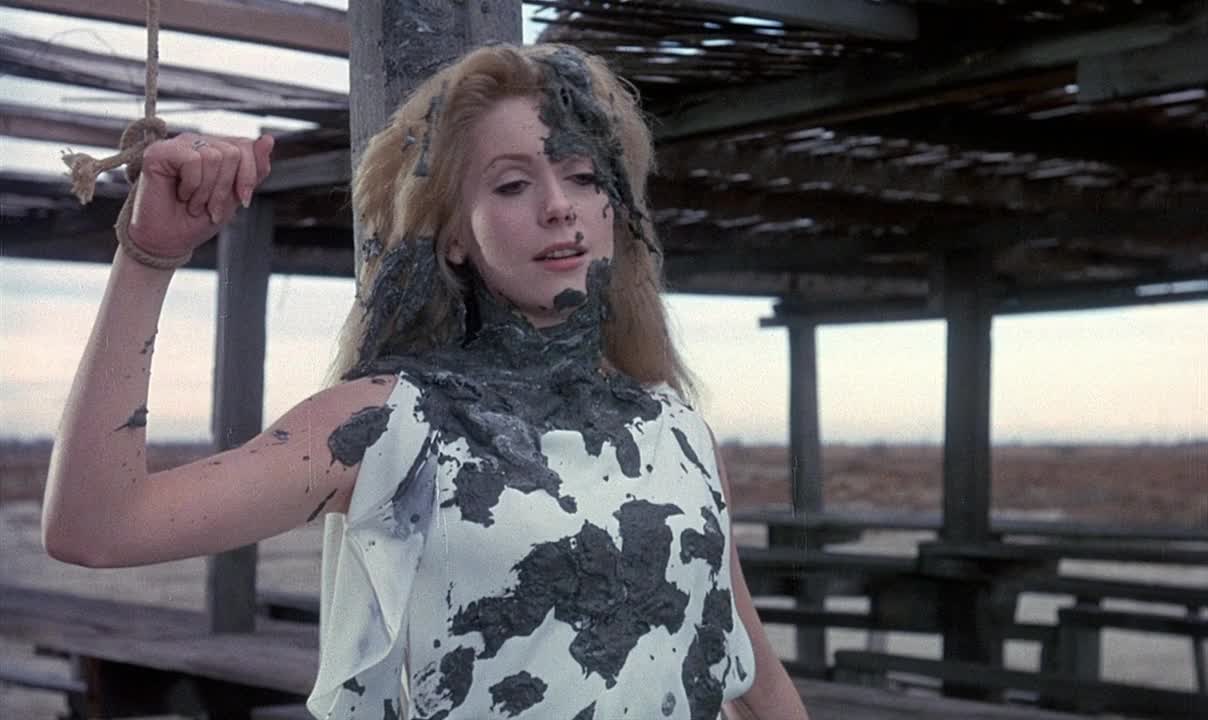

15. Belle de Jour (Luis Buñuel, 1967)

“Belle de Jour” is a film about sex dreams, repressed fantasies, and the wraiths that populate them. Catherine Deneuve plays Séverine, a young housewife who is erotically bored.

While she is happy living with her respectful and chivalrous husband, she cannot achieve the sexual gratification she desires and needs from him, so she starts working at a brothel during the day, changing her name to Belle de Jour (which is French for ‘beautiful by day’).

The tenderness of her husband is contrasted by the violence and abuse she fantasizes in her dreams. The final moments of the movie hint slightly at the possibility that Séverine had been fantasizing the whole time, giving the film a mysterious and surreal nature, perhaps implying that sex is a creative act in itself.

In the heart of the film are themes of repressed sexuality and unsatisfied desires. It provokes us, makes us consider what is it that we are repressing, and how those impulses have shaped our lives and dreams.

Author Bio: Gustavo Toledo was born in Mexico City and he lives there. He is a graphic design student and a freelance writer. After a tragic accident in his childhood that left him homebound for several months he discovered the magic of cinema and now he is passionate about it. Since then all he ever dreams about is making movies.