8. The Grapes of Wrath (John Ford, 1940)

The film version of John Steinbeck’s classic novel holds pretty true to its primary source, although it certainly paints a more optimistic picture. The film follows Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) and his large family as they leave their farm in Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression to seek viable work in California. They face numerous struggles along the way, and Tom eventually adopts a strong belief in the need for social reform and organized labor.

The Grapes of Wrath humanizes itinerant workers in ways that no other film has been able to capture. The clarity between the haves and the have nots has never been more pronounced. The transient camps where the Joads stop are filled with hopeless, starving laborers who want nothing more than an opportunity for honest work. They are continually exploited by land owners, merchants, and law enforcement.

In salient nods to leftism, Tom attends meetings where these workers attempt to organize and potentially strike, only to be maliciously beaten and murdered to prevent such unity. Essentially, The Grapes of Wrath now serves as a reminder about the necessity of solidarity and egalitarianism amongst workers to prevent exploitation.

9. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

Stanley Kubrick’s classic political satire about the Cold War and nuclear conflict takes viewers inside a ridiculous war room where the United States government is trying to prevent a nuclear holocaust that is about to commence because of an insane Air Force Brigadier General.

A group of war planes has been ordered to drop nuclear weapons on the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union has already created a ‘doomsday device’ that will wipe out all animal life on Earth if they are ever attacked by such a weapon. What we are left with is a series of missteps and absurd contradictions that eventually lead to this bleak scenario.

Dr. Strangelove is truly effective in pointing out the major hole in the idea of mutual assured destruction – which many have seen as the reason why no one would ever use a nuclear weapon post-WW2. In Dr. Strangelove, all that it takes is one insane individual who has access to launch codes to prove that mutual assured destruction is not a failsafe deterrent to nuclear war.

In this plot point, the film sharply criticizes the superfluous stockpile of weapons of mass destruction that the world’s superpowers hoard. The military industrial complex, in Dr. Strangelove, maintains its control through extremely tenuous systems governed by people who are naively entrusted to think collectively. While the film is laugh-out-loud-funny at times, the grim reality of militarization and government bureaucracy in the nuclear age indicates a more leftist, peace-seeking worldview.

10. Bethune: The Making of a Hero (Phillip Borsos, 1990)

A horribly under-seen film about a man who has been hailed and immortalized as a hero in China, and credited by many as the father of Western universalized healthcare, Bethune: The Making of a Hero presents the adventurous life of Dr. Norman Bethune (Donald Sutherland). The Canadian doctor made a name for himself by self-administering an experimental tuberculosis treatment and by inventing mobile plasma transfusion kits that could be administered on the battlefield.

While serving as a war medic in Spain, Dr. Bethune became interested in socialism, and particularly socialized healthcare that brought medicine to all citizens of a nation. He eventually travelled to the Soviet Union and China, where, in the latter, he set up free clinics throughout the country.

Bethune: The Making of a Hero has never reached large audiences in the West, largely because of its one-sided portrayal of the Chinese Revolution and Mao Zedong. However, Dr. Bethune became an ardent advocate of the benefits of socialized medicine – a benefit that most Western countries have come to agree with. Sutherland’s depiction of the doctor is complex and interesting, showing a man who devoted his life to compassion, but treated those around him with anything but.

11. Into the Wild (Sean Penn, 2007)

Dramatizing the short life of a young man named Chris McCandless, aka Alexander Supertramp (Emile Hirsch), Into the Wild tells the tale of his two-year journey from his affluent upbringing on the East Coast to a transient lifestyle that would eventually land him living by himself in the Alaskan wilderness.

Through his travels, McCandless forges numerous relationships with others living on the fringes of American society. He casts aside laws and conventions that he deems immoral or unnecessary. All the while, he places importance on living a disciplined, intellectual, and arduous lifestyle in an age where technology makes our lives increasingly sedentary and comfortable.

Into the Wild effectively modernizes the American countercultural tradition of nonconformity that was established by the likes of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

McCandless personifies a rejection of the capitalistic culture of 20th and 21st Century America. He rejects a new car being gifted by his parents; he burns or donates all of his money; he hops trains and moved transcontinentally without the benefit of his own transportation; he forages for and hunts his own food. The extreme anti-capitalism and implied environmentalism makes it an obvious inclusion in leftist cinema.

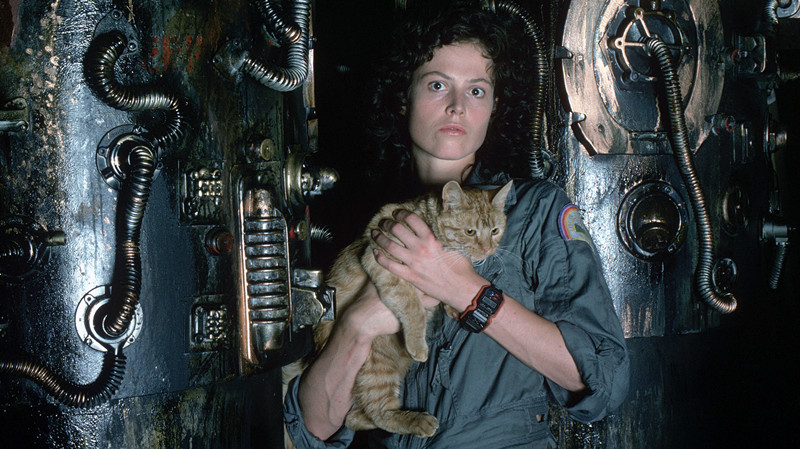

12. Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) & Aliens (James Cameron, 1986)

The first two films of the Alien franchise are truly regarded as having revolutionized the sci fi/horror genre. Never before had space travel been presented as so dirty, gritty, claustrophobic, and blue collar.

The constant levels of tension and anxiety that permeate both movies, only to be interrupted by captivating moments of action and violence, set the bar for the genre for decades. Both films, while different in tone and pace, focus on the “accidental discovery” of a highly lethal alien species on a remote planet. In each, reluctant heroine Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) is all that stands between the deadly creature(s) and humanity.

While the impact of the two films on the realm of sci fi is undeniable, the inherent leftism of the films should not be ignored. Beneath the atmosphere of terror, there lies harsh criticism of unfettered corporate greed, militarism, exploitation of workers, and patriarchy. In the first Alien, we learn that the Weyland-Yutani Corporation that owns the ship has ordered android Ash (Ian Holm) to capture the Alien and bring it back, even if it means all of the crew dies.

This underlying narrative is taken even further in Aliens, when the same corporation has become intertwined with the military, and the purpose of its mission is to make the alien species into a biological weapon. In both films, corporate greed overshadows individual lives, which are expendable when compared to potential profits and military prowess. Likewise, in both films, a strong, independent female protagonist accomplishes what none of her better trained male counterparts can.

13. The East (Zal Batmanglij, 2013)

The East is a film that delves into the world of an underground radical ecological activism group. The protagonist of the film is Jane Owen (Brit Marling) who is a secret operative for a private intelligence firm. She is tasked with infiltrating the “terror” organization called The East, which has been responsible for a number of attacks against multinational corporations.

Jane eventually gains the trust of The East and becomes close with the movement’s magnetic leader Benji (Alexander Skarsgard). As she engages in missions with the organization, Jane’s allegiances shift and she comes to side with the organization that she was hired to help take down.

While Jane’s transformation is predictable, the film succeeds in making viewers see the organization’s actions as just. It is learned that every member of The East has been directly harmed by the very corporations that they level attacks against. Their mission is to seek justice and expose the immoral activities done in the name of profit.

The film is highly anti-capitalistic in its tone and themes. While some of the deleterious actions committed by the corporations may seem extreme, the film is careful to not paint them entirely as caricatures. The mixing of personal and political motivations of the members of The East, make their motivations more compelling and relatable.

14. Full Metal Jacket (Stanley Kubrick, 1987)

While any number of war films could have been selected for this list, Full Metal Jacket stands out as a leftist film, not for overt antiwar messages, but for a more nuanced critique of the military, hyper-masculine mindset and the total cost of war. The film itself is broken into two parts: one occurring in Marine basic training and the other in Vietnam around the Tet Offensive.

In basic training, the main character Joker (Matthew Modine) endures the harsh training of his drill instructor (R. Lee Ermey). This treatment leads directly to the complete mental breakdown of one of Joker’s fellow trainees (Vincent D’Onofrio). While in Vietnam, Joker is a war correspondent who lives through the Tet Offensive and then is embedded with a unit that eventually takes heavy casualties from a single sniper.

The reason Full Metal Jacket stands out as a leftist commentary has largely to do with its more holistic focus on the overall military mindset. The tactics of the drill instructor are aimed at breaking men down so that they can be built back up as killing machines. Joker is reluctant to this training, as he has antiwar leanings and sees himself as a complex individual, rather than a singularly focused machine.

The effects of this training, as mentioned above, drive another Marine to madness. Then, when the film shifts to Vietnam, the corrupting nature of warfare becomes the focus. Obviously, soldiers are killed, wounded, and traumatized. They revert to their most base and masculine tendencies, which viewers should look upon with sadness and contempt. But Kubrick’s film also shows the corrupting nature that the war had on the Vietnamese civilians.

A mass grave is shown at one point. Civilians are driven to prostitution and theft. Teenagers, even young girls, are recruited into the war effort. All the while, Joker wears a peace sign pin on his helmet and unsuccessfully seeks humanity in the face of mental, emotional, and physical destruction.

15. Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982)

Another sci fi movie by Ridley Scott, Blade Runner is set in a future Los Angeles where Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is tasked with hunting down and “retiring” rogue replicants – robots who are almost indecipherable from humans. In this future, the Earth is badly polluted and most humans have moved off of the planet – they are gifted personal replicants as incentive. Deckard spends the film tracking down the replicants, largely through investigating the Tyrell Corporation that makes them.

Much like the Alien Films, Blade Runner has pretty salient criticisms of corporate greed. But adding to this theme, and having the film veer more clearly into leftism, is Blade Runner’s focus on humanity and what it means to be human. The way to apparently tell a replicant from a human is through the replicants’ inability to feel empathy. However, both Deckard and viewers soon learn that it is actually the humans who lack empathy.

The replicants are programmed to only have a four year lifespan, and the rogue replicants have illegally headed to Earth to attempt to prolong their time. The human reaction: kill them sooner. Additionally, the climax ends with the lead replicant (Rutger Hauer) completing a selfless, truly empathetic act. The defining characteristic of morality and humanity in Blade Runner is self-sacrifice for others, an obviously leftist viewpoint.

Author Bio: Cole Gelrod is an English educator and freelance writer. He lives in Denver, CO.