8. Short and Sweet (1936 and 1991)

Its easier to win an Oscar with lots of footage in which to emote. However, there are some performers who have made a lot out of a little and others who got an Oscar for a few minutes and no one can figure why. The Best Actress Oscar of 1936 is a good place to start. The Academy very nearly went under in the mid-1930s thanks to lots of bad blood over industry politics, mostly between management and the various guilds in the motion picture industry.

1935 was almost Oscar’s last bow. Well, several concessions saved Oscar, some of which didn’t last (best assistant director and choreographers awards, allowing screen extras to vote in Academy matters) and some did, namely awards for supporting players (before that the theory went that anyone could win, regardless of role size, but only two supporting players were ever even nominated in those years).

However, it took some time to get who belonged in what category right (if it ever has been gotten right). 1936 saw Best Actress given to a performance which only took up some fifteen minutes in a three hour film, and which contained only one big scene. The Great Ziegfeld, a sort of cod bio of the great theatrical impresario Florenz Zeigfeld, was typical MGM, big, glossy, a bit empty, but entertaining.

It’s Oscar for Best Picture was dubious enough but Best Actress went home with Luise Rainer, an Austrian stage actress making only her second film. She played the first Mrs. Z, continental stage star Anna Held. After the eventual couple shares a cute meeting scene, Anna is mostly just seen sitting next to her husband in reaction shots as they watch his big shows.

They break up off screen and he marries actress Billie Burke (who often worked at MGM but who was played here at Powell’s eternal co-star Myrna Loy). It looks now like someone thought that Anna’s story arc needed to be resolved after the and thus she has a scene where she calls her ex and tells him how happy she is for him, though anyone can see her heart is breaking.

It’s not that good a scene but, unbelievably, at the time it was considered the most perfect piece of acting captured on film! (The big thing is that there is no cut away to Ziegfeld on the other end, so Rainer has to hold the screen alone for the duration of the call.) Rainer won an even less deserving Oscar the very next year (studio politics again) before descending into obscurity, though she did live to be 104.

By contrast the shortest Best Actor performance is Anthony Hopkins’ iconic work in 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs. He had earlier won the several supporting awards from various critics’ groups and the film’s studio, Orion, wanted to mount a supporting actor campaign for Hopkins but the actor, who had never been previously nominated at the time, put his foot down and said lead or nothing.

When he got the nomination many wrote the film off since it had just missed the previous year’s awards and The Prince of Tides Nick Nolte was favored to win Best Actor. In retrospect, it would have been a shame if it had gone to anyone else. Hopkins may only have had ten minutes in the film but they were unforgettable and he and character Hannibal Lecter are now part of film history.

9. Double Pleasure (1944)

In its earlier years, the Academy sent out ballots containing three blank slots for the categories in which the recipients could vote. Blank one would be worth the most points, two the second most, three the least. They made no direct limitation about who could be written in. This worked rather well for years but then 1944 saw a most embarrassing situation occur which caused a big rule change.

The biggest grossing film of that year (though certainly not the best, Oscar notwithstanding) was the ultra sentimental ecclesiastical comedy-drama Going My Way, the tale of a progressive young priest (Bing Crosby) gently replacing a crotchety but lovable old priest (Barry Fitzgerald).

Though Crosby, a huge star at the time, was unquestionably the lead, Fitzgerald, a most distinguished character player, who started out with Dublin’s famed Abbey Players, had a more sizeable supporting role than the norm.

That may well account for the fact that he had enough people fill in the blanks for him on the ballot to end up getting nominated for both Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor for the same film! Well, if anyone did deserve something for that film (besides director-writer Leo MacCarey, who had a genius for pulling off this kind of drivel), it was Fitzgerald and his flavorful performance.

However, if he had to be awarded, it’s a shame he couldn’t have been given the lead Oscar and left the supporting one to Clifton Webb’s fine performance in the mystery classic Laura. Needless to say, though the doubling was allowing to stand, the rules changed thereafter and this sort of thing can never happen again.

10. Oscar’s Big Upset (1947)

From the late 1930s until they wised up and stopped it in the mid 1950s, the motion picture trade paper The Hollywood Reporter made a habit of polling Academy members (calling it a “straw poll”) and publishing the results.

They were correct a large part of the time but either their poll didn’t have enough of a sampling or those polled weren’t always honest, for they did have some slip-ups and none was ever more jaw dropping than the race for Best Actress of 1947. 1947 wasn’t that great a year in movies or other places (the clouds of the blacklist were already appearing and shaping things).

A lot of categories were up for grabs. Ronald Colman more or less won Best Actor for his lesser work in A Double Life by having his agent say that he was about to retire and this was probably the last chance to award him (and he, being a gentleman, he more of less did, and it was). In this chaotic atmosphere, veteran actress Rosalind Russell thought that she might well have a great chance at Oscar for her work in RKO’s adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s monumental stage trilogy Mourning Becomes Electra.

Never mind that virtually no critic had a kind word for it and it ended up being just about the worst flop in that studio’s disaster laden history. She hired the publicist who helped Joan Crawford get her Mildred Piece Oscar two years before and prepared for victory (though the fact that Crawford was making a big comeback in an acclaimed hit might have helped her case).

The straw poll stated that Russell would win over Crawford herself (for Possessed), Dorothy McGuire for that year’s eventual Best Picture, Gentleman’s Agreement, newcomer Susan Hayward for the indie drama Smash-Up, the Story of a Woman, and, most especially, Loretta Young, who had been around longer than any of them and was up for a pleasant but rather light political comedy-drama entitled The Farmer’s Daughter. Young was respected enough but not nearly as popular or as acclaimed in the Hollywood community as Russell, who was a tireless charity worker and adept at both comedy and drama.

The poll more of less stated that Young should just stay home but she did come anyway in a plush green dress (and green is supposedly an unlucky color). To the shock of everyone (especially Russell, who snapped her pearls), Young’s name was called out (she asked to see the envelope after mounting the podium). She was gracious but the how of it all is a mystery to this day.

One odd fact: Young was chosen to hand out the Best Picture award for 1981. The smart money was on Reds or On Golden Pond, maybe Raiders of the Lost Ark. Instead she presided over another surprise by announcing the winner to be Chariots of Fire, which had been about as much chance to win as she had been given.

11. Supporting Matters (1952, 1959, and 1976)

The supporting category often is treated like some sort of bargaining chip in a game. Though good supporting and/or character players are essential of almost any film, these categories often get used in a more political way than the leads.

A perfect example of this is the supporting awards for 1952. The infamous straw poll indicated that the winners would be Richard Burton for Fox’s period mystery My Cousin Rachel and Gloria Graham for MGM’s big Hollywood expose, The Bad and the Beautiful, though she only had about five and half minutes of screen time.

Burton would not win and rightfully so. Disregarding the quality of his performance, his character was the “my” of the title, narrated the film, and, since the action was all told through the character’s eyes, was in every scene, longer on screen than even star Olivia de Havilland !

This was a classic attempt to push a lead performance into a supporting slot for an easy Oscar. Oddly enough, true supporting actor (at the time, anyway) Anthony Quinn rightfully won for another Fox film, director Elia Kazan’s Viva Zapata! Graham was another matter.

Though off-beat in her kittenish-tigress looks and demeanor, she was a fine actress, if a mess as a human being. She had worked a lot for meager rewards. MGM was undoubtedly pushing their big film but she was having a great year in 1952, also appearing in that year’s really dubious Best Picture The Greatest Show on Earth and the film noir classics In a Lonely Place (she was the female lead) and Sudden Fear (for which a nomination would have made sense). Her Bad and the Beautiful performance, somewhat based on Zelda Fitzgerald, didn’t give her that much with which to work.

Though she surely deserved an Oscar sometime for something (though her career troubles made this her second and last nom), this Oscar wasn’t the one. It belonged to Singin’ in the Rain’s immortal Lina Lamont, Jean Hagen, another tough luck Hollywood gal.

Also to be noted, in 1959 veteran British stage and film actress Hermione Badderly, a wonderful familiar face, received the nomination for the shortest performance in Oscar history for the classic British kitchen sink drama Room at the Top. It was a superb film but her recognition for only two and half minutes work, spread out, not in one big scene, makes little sense other than a good film had a good publicist.

In 1976, Graham’s record for shortest performance to ever win was taken away by noted New York stage actress Beatrice Straight (who had also been a familiar face on early, New York based, live TV) for the now iconic satirical drama about the TV industry, Network.

As she said in her eloquent acceptance speech, she was the dark horse, and it wasn’t the strongest of races but her role, which almost literally was one big scene, gave her five electric minutes and she showed that it can be done in that short a space of time.

12. 1963’s Most Messed Up Category

Looking at the records, the award for Best Supporting actor of 1963 doesn’t seem so unusual. It went to the most distinguished Melvyn Douglas, a film, stage, and TV staple since the early 30s, for his turn as the roguish title character’s principled old dad in the excellent modern day western Hud (and many thought it high time for him to get something).

There was also a delightful comedy performance by Welsh actor Hugh Griffith for that year’s Best Picture winner, Tom Jones (though Griffith already held a shaky Oscar for his supporting turn in 1959’s Ben Hur).

No, the problem was with two men who saw fate rob them of any chance they might have had at the award. 1963 wasn’t a great year in film and MGM found itself to be no exception. Outside of the spectacle How the West Was Won, which it co-produced with the Cinerama Company and which was no critical darling, it had little of note.

One was the glossy, star studded film The V.I.Ps, which won a deserved Oscar for the great comic actress Dame Margaret Rutherford but the only other thing in the company’s vault was a really drab courtroom drama entitled Twilight of Honor. The film was one of the studio’s several unsuccessful attempts to make a movie star of their Dr. Kildare TV star Richard Chamberlain.

Well, the preview screening of the film netted the TV guy nothing but those who saw it were impressed enough with the big scene given to character actor Nick Adams, who played the defendant. Too bad the editing department didn’t get the memo for it trimmed the film for general release and, yes!, the editors cut out Adams’ big moment! Even worse, they made no attempt to put it back after the nominations. All that was left of his performance was a few lines of dialog and a handful of reaction shorts.

Anyone coming on the film now, not knowing the back story, would think that the Academy had lost its collective mind nominating him. An even worse fated met Roddy McDowell. He had been a film staple since he was a literal child and gave his best film performance as the spidery and cruel Emperor Octavian in Fox’s famously troubled Cleopatra.

Fox believed in Oscar more than probably any other studio and had an infamous history of netting undeserved noms for its films, so it would have been happy to get some notice for one of the few good spots in a film that was taking them to the cleaners.

Unfortunately, the Academy accidentally left him off the nominating list and McDowell, under the rules, could not be nominated. This is especially sad in that this was as close as he ever got to having the industry he toiled in for so very long recognize that work.

13. A Question of Timing I (1972)

One of the Academy’s more stringent rules is the fact that if a film doesn’t play in Los Angeles then, well, it doesn’t really exist. Well, since many Academy members live there, that might not be so absurd a rule (though in the age of video it’s become rather moot). The oddity of all this was brought home by the only Oscar the great Charles Chaplin ever won in competition…and about the least deserving nomination of his career.

In 1952 he had just completed a rare drama for him about an aging and washed-up music hall clown finding bittersweet and momentary love with a sad young ballerina whom he inspires. It was called Limelight and, though it was quite sentimental, it contained a number of fine elements, including the excellent performances of Chaplin and then-newcomer Claire Bloom as the young woman.

However, Chaplin’s infamous political troubles came to a head just before the film was released and, during a trip he took to Europe to relax from making the film, he learned that he might well not be allowed to return to the US. He didn’t come back until given his second special Oscar in 1972. Los Angeles being a company town and never liking that Chaplin had lived there for so long without ever becoming a citizen, was in no hurry to show or even see Limelight.

Cut to twenty years later. Times had changed and so had the attitude towards Chaplin. A theater actually showed Limelight in Los Angeles! Never mind that the rest of the world had known of the film and acclaimed it for two decades, now it was a real film. Did the performances of Chaplin and Bloom get nominated? How about Chaplin’s direction or script? No. However, the score, which Chaplin helped to create, did win.

Chaplin was famous for working on the scores of his films but those who worked with him in that capacity say that he couldn’t truly compose music since he could neither read or write music. He would sort of concoct melodies in his head and hum them to the composers working with them would transcribe into actual music. So, he sort of composed, but one wouldn’t look at his composing too closely. Just as odd, actress Candice Bergin picked up his Oscar for reasons unknown.

14. A Question of Timing II (1974)

When the nominations for 1974 were announced there was a lot of good work rewarded (it was a prime year for the New Hollywood period). This did not include the nomination given to the great Swedish born film star Ingrid Bergman for her not especially notable work in the British shot murder mystery Murder on the Orient Express.

Now this lady was incapable of giving a bad performance but her smallish and drab role as a missionary didn’t provide much a challenge. Even though Hollywood had welcomed her back after an infamous scandal which had driven her to Europe by giving her a somewhat iffy Best Actress Oscar in 1956 (for Anatasia) it must have still been feeling guilt for it gave her the 1974 Oscar as well.

The classy Bergman got up and said that it was always nice to see Oscar and then started talking about the performance of one of the other nominees, namely Italian actress Valentina Cortese, who had given a perfectly wonderful performance as an addled veteran film actress in French director Francoise Truffaut’s now classic movie making film Day for Night, significantly the winner for Best Foreign Film in 1973.

Under the rather arcane rules the Academy, no friend to films from outside Hollywood, had in place was one stating that if, and only if, a foreign film won in that category could it be eligible to be nominated in other categories THE NEXT YEAR (effectively killing what buzz the film might have).

Cortese’s performance had been much acclaimed and she had won many critic’s circle awards but the Academy did her in. Bergman literally apologized from the stage for winning. It would have been a nice moment but one of the other nominees, Diane Ladd of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, took umbrage to Bergman singling out one performance. The well intentioned Bergman then opined that maybe she should have said thank you and left it at that.

15. Oscar’s Most Unusual Nominee (1966)

Many great actors have been honored by the Academy and many have not and very many have gotten into the golden circle only once despite a career full of fine work and some just happen to be in the right place at the right time. In this later group falls a woman who must be the most unique acting nominee ever.

When the Mirisch Brothers bought James Michner’s mammoth novel Hawaii in the early 1960s, they knew that there were going to be a lot of logistical challenges (there were but professionalism kept the production rather steady). However, there was one big, big problem which had to be solved.

One of the key supporting roles was the character of the intensely obese island queen Malama Kanakoa, whose warm heart lies under an honestly abrupt, child-like exterior and whose embracing of Christianity paves the way for the main characters to settle on her island, though she secretly retains her incestuous pagan ways.

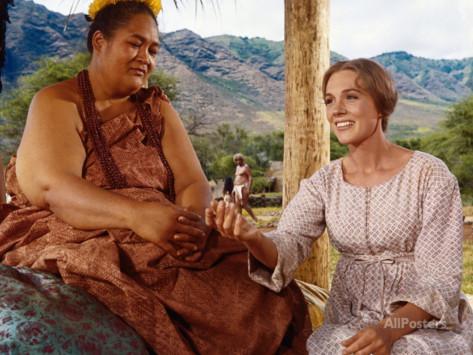

The character could not be written out and yet no professional could be found who could play the role without coming across as phony. Talent scouts searching the indigenous peoples of the South Pacific and found an immense woman named Jocelyne La Garde on the island of Tahiti.

To call her a non-professional would be an understatement. She weighed 450 pounds and spoke no English, only her native tongue and French (and apparently was illiterate in both). Not only was she not trying to be in a movie and but no one was ever sure if she had ever actually seen one.

Though she had to be fed her lines phonetically, she fit the part and was soon acting alongside Julie Andrews, Richard Harris and, especially, the great Swedish actor Max von Sydow, who was meant to be the austere, scarecrow like opposite number of her warm, fleshy character.

Well, it worked. She virtually stole the show and ended up nominated. However, it washed over her. If she had a reaction, it was not recorded. She did not show up on the red carpet. She never got anywhere near another film set and died about a dozen years later, apparently not pining for her lost close-ups. (To this day she is the only person nominated for an acting Oscar in their only film.)

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film, cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.