For some only a consolation prize, but for others a good way to get recognition, the Cannes Grand Prix prize will have people always talking about it and its winner. It is responsible for introducing many film lovers to a variety of film sub-genres ranging from Yugoslav black wave comedies and guerrilla-style social dramas from Burkina Faso to hyper stylized Korean thrillers and French LGBT sociopolitical tear jerks.

Here are the top 20 that best represent what this award can offer.

20. Night of the Shooting Star (Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, 1982)

The Taviani brothers entered the scene with their unexpected win at the Cannes in 1977 with “Padre Padrone”. While it wasn’t a good film, per sé, it opened the door for the gifted directors to continue to work and eventually make a masterpiece. And that they did, five years later.

Placed in beautiful Tuscany, the film is a story about a fight against fascists, viewed from a point of regular working peasants, the directors’ favorite demography to show. While the film is simple in its structure and postulate, it exudes with complexity in its display of humanity. Many scenes will be left carved in the mind, and many of them will not leave a pleasant afterimage, but at the end of the day you will walk out of the film feeling warm.

19. A Prophet (Jacques Auidard, 2009)

Jacques Auidard’s debatable master work is a thrilling ride through the hierarchy of prison, similar to “The Shawshank Redemption” but without cheap sentimentality and with grim realism in every frame.

Tahar Rahim is the shining star of the film as he slowly turns from a marionette to someone who is pulling the strings, without the film showing us what he thinks in any given moment; everything is presented through mimicry and stature of young talent. Two hours and 20 minutes will pass in the blink of an eye, while the protagonist is pulling out from the hands of the ruthless Céasar, subsequently overthrowing him. A real treat for the adrenalin.

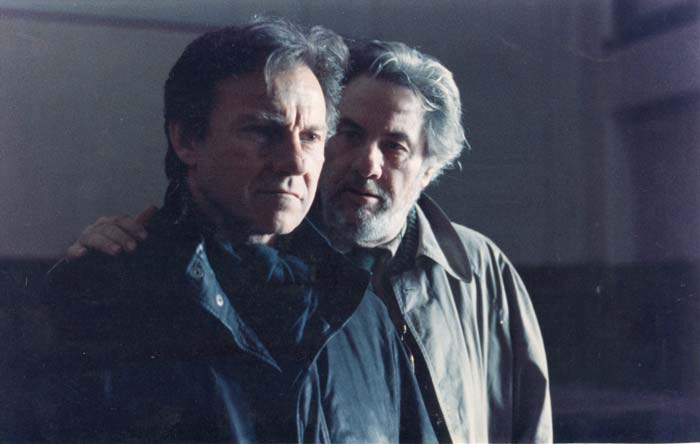

18. Ulysses’ Gaze (Theo Angelopulos, 1995)

It seems that in 1995 all eyes of Cannes were fixated on Yugoslavia, that is, at what was left of it, so the two top prizes of the festival went to films that depicted the wars that led to the dissolution of the country.

The Palme d’Or was won by Kusturica’s over the top yet heartbreaking farce “Underground”, and the Grand Prix went to the more somber “Ulysses’ Gaze”. The film is a real journey (an odyssey, if you will) through the Balkans, that small but anguished region of southeast Europe, all the while exploring and explaining the ethnic tensions that rule the peninsula.

Four scenes leave a long lasting impression: the nightmarish beginning in Greece, in which the protagonist returns from a self imposed exodus, only to be welcomed by an angry mob with torches; the crossing of Albanian mountains, where the most beautiful shots were immortalized; the long and exhausting trip on Danube, with a glimpse at the ruined Lenin statue; and the arrival and sojourn at the fog bound Sarajevo, at the time still devastated by the ongoing war, where the most impressive part of the epic plays.

While it sometimes drags on and is pretentious (primarily in love and scenes with the statue) under the visionary direction of Angelopulos and great acting from Harvey Keitel, “Ulysses’ Gaze” is an unforgettable experience. Negative press followed the film for years, primarily because of the ungrateful behavior of the director while getting the award, but that didn’t affect the quality of this timeless story.

17. Johnny Got This Gun (Dalton Trumbo, 1971)

The first and only film by the great Dalton Trumbo, the genius screenwriter of some of the most beloved Hollywood movies, unfairly blacklisted during the McCarthy era, is one of the most terrifying and most haunting movies ever made, if not due to the frames and scenes, but for the idea that a person, wounded by a grenade, is left without limbs, sight, hearing and the ability to talk. What kind of world is that where the ability to communicate is almost eradicated?

The task of this film is to show us this dread. Presented ideally in a dual variant where the black-and-white world shows the unfortunate present, where he tries to “live”, while the color world shows his recollections of a life long gone, his loves and childhood – the only thing that keeps his psyche as a whole. But as time passes, so do his memories became more lucid and pessimistic, alluding to his increasingly crumbled state of mind.

Those few good situations that happen to him get quickly suppressed by the upcoming dose of brutal reality, only in the end to leave our protagonist in a state, not living nor dead, to helplessly in his head call for any kind of help. This anti-war film, because of which you won’t feel any happy thoughts, was the main inspiration for Metallica’s video for “One”.

16. Son of Saul (Laslo Nemes, 2015)

Just when we thought that we’d seen it all from Holocaust movies, a theme done to death in this day and age, this feature popped up and showed us this unfavorable theme in a fresh and innovative way.

At Auschwitz in 1944, the viewer is put in a situation to literally follow one of the members of a Sonderkommando, a group of selected imprisoned Jews who had the duty of removing the corpses from gas chambers, while he tries to smuggle his alleged child to bury him with honors from a rabbi.

The film is at all times either in first person or in over-the-shoulder point of view of the protagonist which adds to the claustrophobia, adding in another unnerving trait that appears while watching it. The horrors of concentration camps can be seen in every frame, but they are situated in a corner of our periphery sight, giving the viewer enough space to imagine the evils around the protagonist by himself. There is no time for rest for 100 minutes of film’s duration; the viewer will feel constant nausea and the end will leave him to think for days about the selfishness and hopelessness the feature shows.

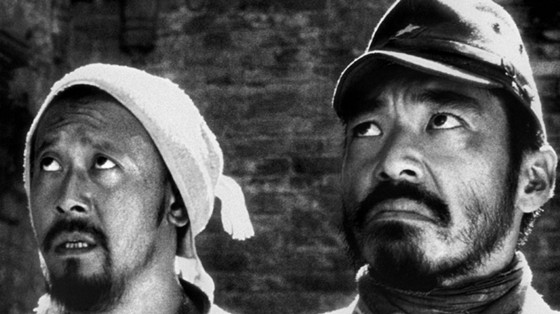

15. Devils on the Doorstep (Jiang Wen, 2000)

War, like the movies that are inspired by that theme, is disgusting and horrifying; it shows the worst of human nature. This film is the same, aside from one little difference, and that is that you’re going to roll on the floor from laughter in particular scenes. This is tragicomedy at its finest and the fact that it is a war movie makes it even more brutal.

Roughly 140 minutes of beautiful black-and-white cinematography where the actors are trying to scream their lungs out, while they’re finding themselves in comedic situations (such as threatening the Chinese) that, in a moment, throw the viewer off from the uptight feelings, only to return later with a cold slap or realism.

This movie was banned in China (PR) for years, because the last scene (the only one in color) indicated that the problems shown on the silver screen can easily be parallel to the state of the country at that time, but even with that, the movie survived and became one of the most celebrated works from the mainland, ever since the works of the fifth generation.