14. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, I Know Where I’m Going, Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes, The Tales of Hoffman, The Battle of the River Plate

Although this iconic duo are better known for the sumptuous Technicolor cinematography of their films, Powell and Pressburger handled important, timely and hugely entertaining themes with an astounding balance of repression and flair. Their screenplays, especially those of “Black Narcissus” and “The Red Shoes” are tautly structured, but engage so directly and proactively with the audience, we are left utterly spellbound.

Their defining characteristic was an eye for beauty greater than what the average filmmaker could conjure up with the resources and conventions of the time. Their films contain incredible wit and honesty. The dialogue is refreshingly direct and lean but never underestimates its audience’s intellect.

Although popular opinion finds “The Red Shoes” to be their masterwork, it’s “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp”, a thunderous, deviously hilarious lore that handily lands them a spot on this list, even if it’s the actors that are largely responsible for bringing the adept script to life.

13. Michelangelo Antonioni

Il Grido, L’Avventura, La Notte, L’Eclisse, Red Desert, Blowup, Zabriskie Point, The Passenger

Antonioni’s genius has been attributed far more to his visual proficiency and lyrical, sensual camera movements and use of music than to his writing. But the vision of the untethered, experimental filmmaking that defines Antonioni’s art can be accredited to his purposefully limitless screenplays that reflect a weightless, adventurous sense of provocation that lends itself to such effective results onscreen.

Antonioni cemented his auteur status with his trilogy of “L’Avventura”, “La Notte” and “L’Eclisse” that brought him much international acclaim purely for the reason that no one was making films like this at the time, and perhaps no one ever had. “L’Avventura”, which was initially booed at the Cannes Film Festival, has quietly proved to be the most enduring achievement of his career.

Often what the characters say in Antonioni’s films doesn’t make much sense. The dialogue has its own absurd rhythm, which although hard to follow, can be sensed at all times. Most of Antonioni’s work could be dismissed as pretentious, forced subversion. But look closely, and you will find a mysterious longing to attain something beyond what is within reach that make his films inexplicably seductive.

12. Aaron Sorkin

A Few Good Men, The American President, Charlie Wilson’s War, The Social Network, Moneyball, Steve Jobs

Perhaps the only screenwriter whose name is at times more prominent in a film’s advertising than the director, Sorkin has certainly made cinema as much a writer’s medium as it is a director’s. His screenplays are exquisitely detailed, nuanced character studies, with each word and character movement bustling with combustible energy.

He seems to have invented the “walk and talk” style of writing, where the characters are constantly moving from one place to another, all the while rapidly spewing dialogue sharper than what lesser writers manage in ten films. He won a well-deserved Oscar for his work on David Fincher’s “The Social Network”, which certified his command over this style and how when in collaboration with a visionary filmmaker, it can make language feel like music.

But his latest “Steve Jobs” might be an ever superior screenplay, even if the film is a tad less cinematic than the Fincher. Fitting enormously insightful details of the life of a tech icon in two hours and three acts like this does, with the actors’ performances, especially one from a transfixing, possessed Michael Fassbender, elevating the material to the level of irresistible style and emotion, Sorkin will probably never be better. Too bad the Academy didn’t even consider it worthy of a nomination.

11. Abbas Kiarostami

Where Is the Friend’s Home?, And Life Goes On, Through the Olive Trees, Close-Up, Taste of Cherry, The Wind Will Carry Us, Certified Copy, Like Someone In Love.

Easily the greatest cinematic poet of all time, Kiarostami’s peculiar style of filmmaking defies standardization. He crafts characters that conform so profusely to reality, only to then make them navigate situations in ways so lyrical, so singularly elegiac that the unreal becomes much more enchanting.

He has been often criticized for his discomforting blending of reality and fiction in no conspicuous patterns, especially in his Palme d’Or winner “Taste of Cherry”, where in a few shots even the crew of the film is visible. Roger Ebert claimed it was a pointless “distancing strategy”, but missed how deeply profound the point Kiarostami is making with the film, how observant and non-judgmental his style is.

Kiarostami’s dangerous dismissal of the confines of expectations from his film always befuddled his audiences at first. His dialogue immaculately displays a wisdom so rare in any art form and combined with a consequence-free approach to structure and narrative, his contributions to cinema are bound to be cherished for a long time to come.

10. Wes Anderson

Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, The Darjeeling Limited, Fantastic Mr. Fox, Moonrise Kingdom, The Grand Budapest Hotel

A hipster who can make you believe that the love of two twelve-year olds is eternal and all-consuming can pretty much get away with anything. We’re fortunate that his authority over a quirky, humorous, wryly melancholic format that he seems to have invented never wavers. Film critic David Ehrlich once noted that Wes Anderson has never made a bad film, and he probably never will, and his claim can be substantiated by the consistent success Anderson has had with perfecting his style with every project.

Like Sorkin, he has been a game changing force in the screenwriters community, deftly layering most of his screenplays with childish tanginess and a serenely nostalgic handling of human relationships; perhaps best exemplified by “Moonrise Kingdom”, arguably his most intricately and intelligently realized film that benefits from a memorable screenplay he wrote with frequent collaborator Roman Coppola.

9. Charlie Kaufman

Being John Malkovich, Human Nature, Adaptation, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Synecdoche, New York, Anomalisa

Charlie Kaufman is a bewildering artist. His warped perceptions of the world at times beam with hope and verve and at others plunge his films into utter darkness with no respite in sight.

His writing style pulsates with inimitable intelligence which might be conceived by some viewers as a desperate attempt at high-brow filmmaking, but when its wrapped in such heartbreaking honesty as in case of films like “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” and “Adaptation” and even in some resolutely grounded portions of “Anomalisa”, it’s hard to resist.

When he turned to directing in 2008 with “Synecdoche, New York”, even then his bleakly composed script was at the center of it all. Determined to see the most vulnerable and fallible parts of the humans he adorns his films with, Kaufman’s scientific dissection pays off in unconditionally rewarding ways.

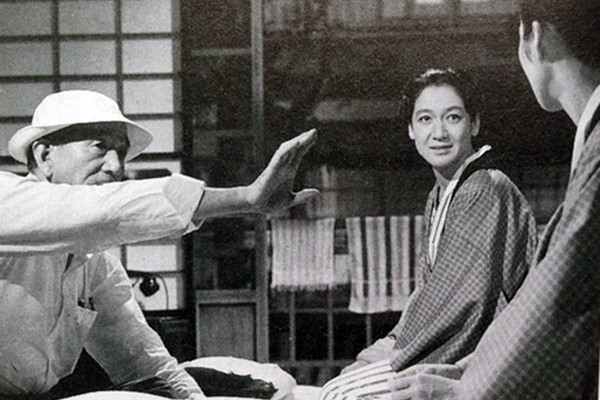

8. Yasujiro Ozu

Late Spring, Early Summer, Tokyo Story, Early Spring, Tokyo Twilight, Equinox Flower, Good Morning, Floating Weeds, Late Autumn, The End of Summer, An Autumn Afternoon

Considered by many filmmakers across the globe as huge cinematic presence of his time, Yasujiro Ozu relayed stories in a way no one else did. So much of work centers on family dynamics and the triumphs and the compromises of building and sustaining a content, stable life.

He understands the flawed human nature so completely and translates it into his refined, gorgeously written films with such little visible effort that his emotional, colorful and at times humorous depiction of human interaction remains unrivaled.

Many film critics call “Late Spring” his masterpiece and while it is a nearly perfect film, it’s hard not to cite “Tokyo Story” his tallest achievement because of the sheer simplicity of the characters and how compassionately it reflects the consequences of change. Through “Tokyo Story”, Ozu’s work remains as heartening and relevant today as it was all those years ago.