9. Jacques Becker’s Casque D’Or (1952), Touchez Pas au Grisbi (1954) and Le Trou (1960)

Jacques Becker, who was during the 1930s an assistant director to many famed directors such as Jean Renoir’s masterpieces La Grande illusion (1938) and La Règle du Jeu (1939), had in Dernier Atout (1942) and Goupi mains rouges (1943) the first successes of his career as a film director. Both these films are crime pieces with a touch of comedy, however, throughout his career, Jacques Becker developed a style that shared many characteristics with noir films. And Casque D’Or (1952), Touchez Pas au Grisbi (1954) and later Le Trou (1960) serve as the best examples.

Casque D’Or (1952) tells the story of a woman named Marie (Simone Signoret) who finds herself divided between the affections of a gangster named Roland, the leader of the a local gang, and the shy honest love of Manda, a carpenter. As described by David A. Cook the film is a “visually sumptuous tale of doomed love set in turned-of-the-century Paris (…) a work of great formal beauty whose visual texture evokes the films of Louis Feuillade and engravings from la belle époque.”

Touchez Pas au Grisbi (1954) is regarded as an important film mainly because it opened the season for gangster films that in the late fifties evaded French cinema. Grisbi as it was titled in English revolves around an aging gangster who sees himself forced to retire and give up the gang’s leadership once his best friend is kidnapped and a handsome ransom is demanded from him.

Memorable by its black and noir cinematography, Le Trou (1960), it’s a tale of human condition that takes place in Parisian prison where four inmates, facing long sentences, plan an elaborate escape which they unveil to the newest member of their cell – Gaspar. Unbeknownst to them is the fact that Gaspar is not the trustable kind.

10. Jacqueline Audry’s Huis clos (1954) and Mitsou (1956)

Jacqueline Audry was what we would call today an indie filmmaker until the end of the 1940s, a period where her adaptations of Collete’s novels became quite popular among French audiences, being its last a subject of this text – Mitsou. However, her best known films are those made during a period of French cinema heavy influenced by American noirs, the 1950s. And in this period, Audry directed an adaptation of Jean-Paul Sartre’s play Huis Clos (English Title: No Exit) which revolves around a group of people, two women and a man, who find themselves locked inside a room in Hell.

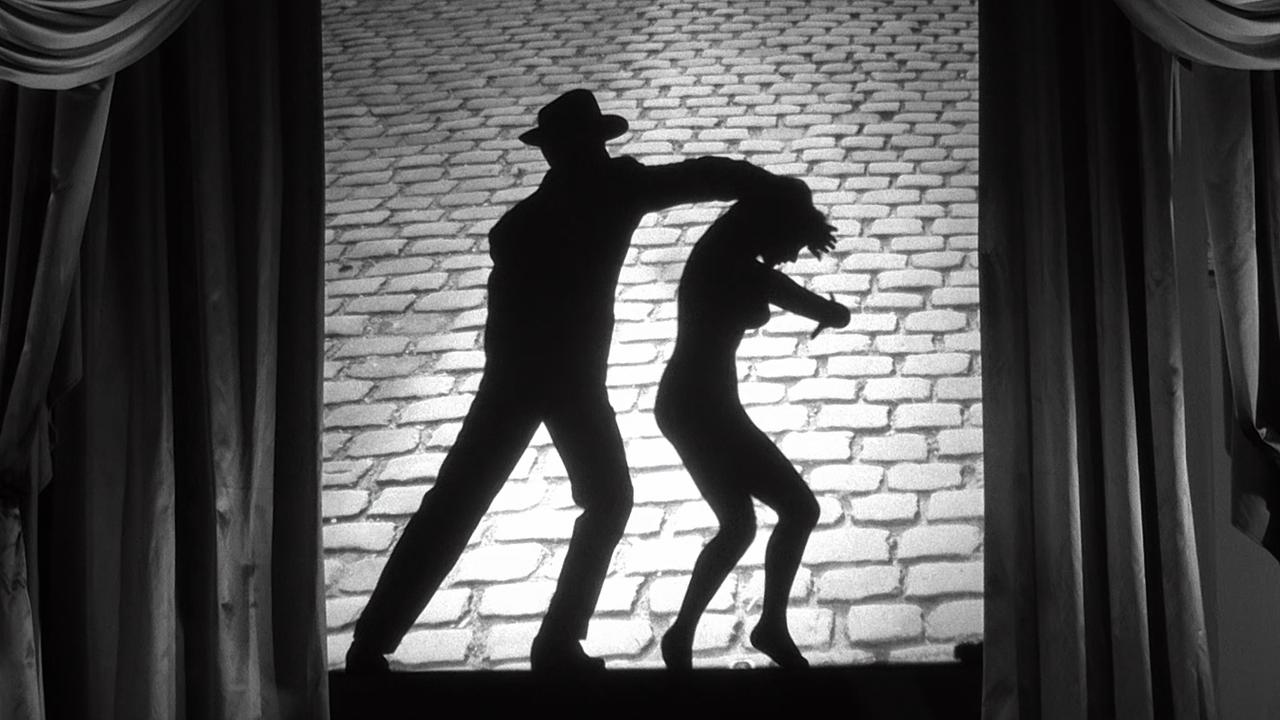

Whereas in 1956’s adaptation of Collete’s novel, Mitsou, the focus of attention is a singer in a Parisian music-hall which finds herself involved in a love triangle. Being at one end an older wealthy man and at the other end a younger army officer who visits the music hall during one of its shows dedicated to the troops participant in the ongoing World War I.

11. Bob le flambeur (1955)

One of the leading figures of what this French noir wave was undoubtedly director Jean-Pierre Melville whose films remain quintessential even today. 1955’s Bob le Flambeur revolves around old Bob Montagne, a gangster who also happens to be a gambler that finds himself amidst total bankruptcy. This forces Bob to make a last effort at regaining financial comfort and social prestige by planning a robbery to a gambling casino.

As noted by film critic Vincent Canby in a New York Times issue, there is a close relationship of influence between Melville’s directorial efforts and the genres that dominated American cinema throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Vincent Canby writes that “Melville’s affection for American gangster movies may have never been as engagingly and wittily demonstrated as in Bob le Flambeur which was only the director’s fourth film made before he had access to the bigger budgets and the bigger stars”.

12. Rififi (1955)

Upon becoming blacklisted by the House of Un-American Activities Committee, American film director Jules Dassin fled to Europe where he then decided to continue his career making some of his most notable films such as Night and the City (1950), The Law (1959) or 10:30 P.M Summer (1966). During this period, another notable achievement was 1955’s production of Rififi.

Shot on a modest budget of approximately 200,000$, this film is focused on the planning and unfolding of the perfect heist by a group of gangsters and ex-cons. Being it memorable by its intricate sequences, its exploration of real time and by an editing style that explored the film’s thrilling elements of violence, danger, greed and of course the run against time which naturally maintained everyone held on their seats.

13. Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (1958)

The second feature film directed by Louis Malle, Ascenseur pour l’échafaud, circles around the macabre plot of Julien Tavernier (portrayed by Maurice Ronet) and Florence Carala (portrayed by Jeanne Moreau), lovers, who plan to kill Florence’s husband. However, things do not happen as the couple had planned and a series of unfortunate events catches up with them.

Featuring a score by influential jazz musician Miles Davis, the film captures the richness of shooting at night, showing Paris with heavy black and white contrasts and capturing its romantic yet mysterious essence. Noteworthy, is also the scene where Julien Tavernier is being interrogated by the police detectives who became increasingly suspicious of the man’s answers and behaviour.

Ascenseur pour l’échafaud is yet, quoting Roger Ebert, another “1950s French noirs (that) abandon the formality of traditional crime films, the almost ritualistic obedience to formula, and show crazy stuff happening to people who seem to be making up their lives as they go along. There is an irony that Julien, trapped in the elevator, has a perfect alibi for the murders he is suspected of, but seems inescapably implicated with the one he might have gotten away with. And observe the way Moreau, wandering the streets, handles her arrest for prostitution. She is so depressed it hardly matters…”.

As noted by Roger Ebert films such as Bob le flambeur (1955), Rififi (1955) and Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (1958), because of their boldness, should be perceived as keys that opened yet another door in French film noir – neo-noirs. Films that throughout the 1960s and 1970s explored noir influences using different rhythms and formal choices.

Later and notable noir influenced films

14. Plein Soleil (1960)

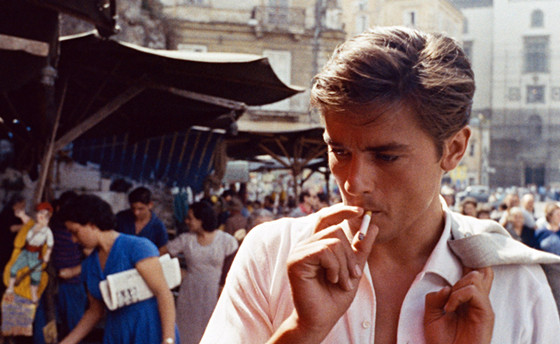

Inspired by Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr. Ripley (who had also written Strangers on a Train adapted by Alfred Hitchcock to the screen), Plein Soleil, directed by René Clément revolves around a man named Tom Ripley, who travels all the way to Italy with the intent of persuading his wealthy friend to take over his father’s estate. However, the friend, whose name is Philippe Greenleaf prefers to spend his time in his luxurious yacht and manages to convince Tom to stay along with him. Tom stays, but for another reason – Marge, Philippe’s girlfriend.

As Tom becomes increasingly attracted to Philippe’s comfortable lifestyle, Philippe on the other hand becomes infatuated with Tom’s constant submissive attitude and to end that Philippe plans a rather cruel little prank on Tom and when it happens Tom’s response is to elaborate a silent yet even more cruel plan – to kill Philippe and assume his identity.

Previously to Plein Soleil, René Clément made equally interesting films such as Les Maudits in 1947, Le Mura di Malpaga in 1949, Jeux Interdits in 1952 or Gervaise in 1956.

Within the same tone and also worthy of your time is La Piscine (1969) directed by Jacques Deray.

15. Tirez sur le pianiste (1960)

One of the most influential films of the nouvelle vague, Tirez sur le pianiste titled in English Shoot the Piano Player, put under focus the destiny of a man once known as one of the great classical pianists of his time, Edouard Saroyan, who started losing his shine after his wife’s suicide. Due to that event Edouard ended up climbing down the stairs of fame being now employed in small Parisian bar as a band pianist under the name of Charlie Kohler.

One night Charlie receives a visit from his gangster brother who manages to convince Charlie to help him in order to get out of a complicate scheme he had with some ‘business associates’. Thus, accidentally dragging Charlie into complicated circumstances.

Even though, visually, the film with its modern editing style (which included jump cuts and other elements that broke with Hollywood’s code of transparent editing which had been applied into film noir) may seem quite distant from its American noir ancestry, the truth is that again the focus on real people that find themselves in out of the ordinary circumstances, as well as, the fact that Charlie is a character that literally descended the stairs from a rich past to an ordinary present can account at some extent to draw a relationship between American noirs and the film itself.

Also important is to note the black and white cinematography by Raoul Coutard that in a way mimics some sequences in noir films, for instance, On Dangerous Ground (1951) directed by Nicholas Ray.

16. Classe Tous Risques and the new wave of French-Italian gangster noirs

As mentioned before, midway through the 1950s and later in the 1960s and 1970s, the noir influence was extended into yet another specific sub-genre of films that became widely popular in French cinema during the referred decades, gangster films, also known as gangster noirs.

These films which were often produced in cooperation with Italian production houses and thus being known as French-Italian gangster pictures, put the focus again in the structure and organization of criminal societies and its dominant values. One of the main examples of this idea is Classe Tous Risques released in 1960 and directed by Claude Sautet.

The film’s protagonist is a gangster that left France before being sentenced to death. In Italy, his new adopted home, he again engages in criminal activities and when the Italian police come closer to him, Abel, returns to France. However, upon returning to France, Abel, his best friend and accomplice, Raymond, as well as, Abel’s family are surprised by the police and, suddenly, Abel sees himself alone while still on the run from the authorities.

Anthony Scott on the New York Times wrote about the importance of Classe Tous Risques, as well as, the significance of gangster films within French cinema of this period: Classe Tous Risques (…) originally released in 1960 was lost in the frenzy of the Nouvelle Vague, which made its straightforward use of genre look a bit old-fashioned. (…) It is worth seeking out, not only because Classe Tous Risques represents a missing piece of film history – a link between the great post-war policiers and the brooding 1960’s gangster dramas of Jean-Pierre Melville – but because it is a tough and touching exploration of honour and friendship among thieves.

Other films regarded as great within this gangster wave were: Les Tontons Flingueurs (1963), Le Clan des Siciliens (1969), Borsalino (1970), Le Cercle Rouge (1970) or Max et Les Ferrailleurs (1971).