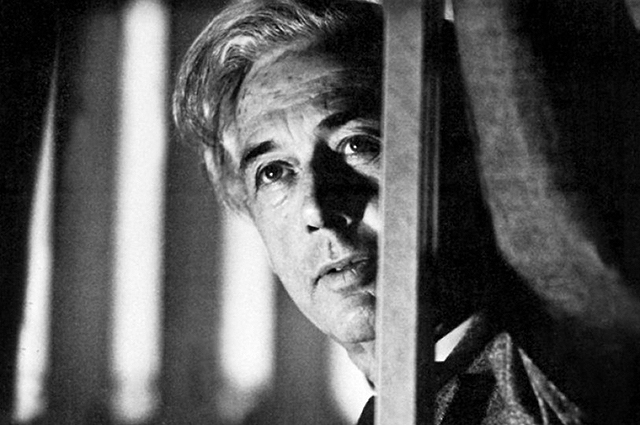

6. Robert Bresson

With the end of World War II, cinema witnessed the rise of great visionaries from all around the world, many of whom tried to experiment with the medium of film and offer alternative grammars for their alternative way of thinking.

Robert Bresson is certainly among those who has created his own “cinematograph” and was a great theorist in film and maybe among one of the few filmmakers who has documented his vision and ideas on film by himself.

Bresson deeply believed that although cinema has borrowed a lot from theatre, it needs to try and create its unique identity, and this is where his unique style comes from. This style included his specific way of assembling / montaging images, which would cut an action down to pieces and hence taking away the theatrical effect; the same was true about acting in his films, as he normally chose amateurs, as well as the use of sound and music which altogether created a very minimalistic style.

Bresson perfected this style throughout his body of work and created a new grammar of film. Great examples of this can be found in his minimalistic masterpieces such as “The Pickpocket” (1959), “A Man Escaped” (1956) or even the fantasy drama “Lancelot of the Lake” (1974).

The latter is a great example where he chooses the famous story of Camelot and the knights of the Round Table, but unlike most medieval adventures or fantasy films, the film does not offer any epic or action element and all the fight scenes are edited in such way that is unusual and alienating to the audience; through this, the film manages to depict an unglamorous image of the Middle Ages and this story.

Or in “The Pickpocket”, the act of pickpocketing is shown through the stylish edits and numerous inserts throughout the film to the point where it was called “Ballet of Hands”. Yet every time the film cuts to the pickpocket’s face, there is no emotional impression on the actor’s face to show what is happening in the scene, and the suspense in the scene and the progression of the action is purely communicated to audience by the editing and montage of the shots.

Bresson has influenced other great names in film history such as Andrei Tarkovsky, Michael Haneke, Jim Jarmusch and the Dardenne brothers, who took the similar minimalistic and poetic style and created their own unique language with it.

7. Sergei Eisenstein

By the time Sergei Eisenstein started filmmaking, David W. Griffith had already established a grammar for film and moving image with his works and among them his grand work “Birth of a Nation” (1915), but Eisenstein, who surprisingly started in theatre, brought the idea of “montage” to film which might be the main dividing difference between cinema and theatre.

This specific use of editing, which was developed and theorized by him and his contemporary, Lev Kuleshov, suggested the collision of independent separate shots will create an idea, while prior to that, editing was only known as a succession of images which are related or linked thematically or graphically.

This new approach became widely accepted internationally and can be best seen in his milestone work “Battleship Potemkin” (1925). Eisenstein made this pioneer film at the peak of silent era, as propaganda for his communist beliefs but also to test his theories of montage. The film is also notable for its episodic structure and has one of the most iconic scenes in the film history – the “Odessa steps” sequence.

It is the best example of Eisenstein’s theory on montage: assembling independent shots together to create ideas and also breaking down an action or event into pieces, and hence creating tension in the scene and more importantly, extending time, which was later mastered by the likes of Hitchcock. Many films have paid tribute to this classic scene, including other classics such as Brian De Palma’s ”The Untouchables” and Francis Ford Coppola’s ”The Godfather”.

Eisenstein was also among the first theorists of cinema and not only did he teach film in the former Soviet Union, but many of his articles have been used as scholarly texts around the world and his theories are still considered fundamental in understanding and learning the cinematic art form. Though faced with a lot of issues throughout his career in his home country and overseas, he made some other major works with sound, including the two epic films “Ivan the Terrible, Part I” (1944) and Ivan the Terrible, Part II” (1945).

8. Federico Fellini

Federico Fellini is another master on this list whose work was a connecting link between classic and modern forms of cinema. First a writer for comedies and radio, he soon became involved with the newly-born Italian neorealism (which offered a totally different approach on storytelling compared to Hollywood cinema) and worked with one of its major figures, Roberto Rossellini, for whom he wrote the classic “Rome, Open City” (1945), one of the most acclaimed neorealist films at the time.

His first films showed the same style in his storytelling, but influenced by psychoanalysis later on, he started to develop a more personal style to depict his memories, dreams and thoughts.

“La Dolce Vita” (1960) is the result of such a style where Fellini offered a new form of narrative through a lengthy nonlinear seven-episode film which avoids traditional plot and character development. To do so, the film deliberately defies continuity of the scenes, and the episodes are not edited to create a narrative logic but instead a state of inconsistency and uncertainty to reflect its protagonists state of mind. The film received a huge critical acclaim and dared to offer a new form of expression in cinema.

Fellini’s major concern was in creating a poetic form of cinema and this style was well reflected in his own words once: “I am trying to free my work from certain constrictions – a story with a beginning, a development, an ending. It should be more like a poem with meter and cadence.”

He moved on to shake the conventions of moving image with yet another major work, “8½” (1963), which is regarded as one of the greatest films of all time. And there is a reason for this flattering title: the narrative of the film (which is about a director dealing with a creative block as well as his personal and public life) is purposefully confusing and the editing constantly switches between director’s dreams and visions and his real life in a nonlinear order, and blends in fantasy and reality and present and the past.

From the very first shot, it seems to be speaking its own symbolic language by the use of bizarre imagery. In other words, he creates a unique grammar in this film which is interpreted by many critics as a demonstration of a dream.

The new narrative form Fellini offered has long been inspiring and influencing many other great directors, including David Lynch, Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam and Woody Allen, just to name a few.

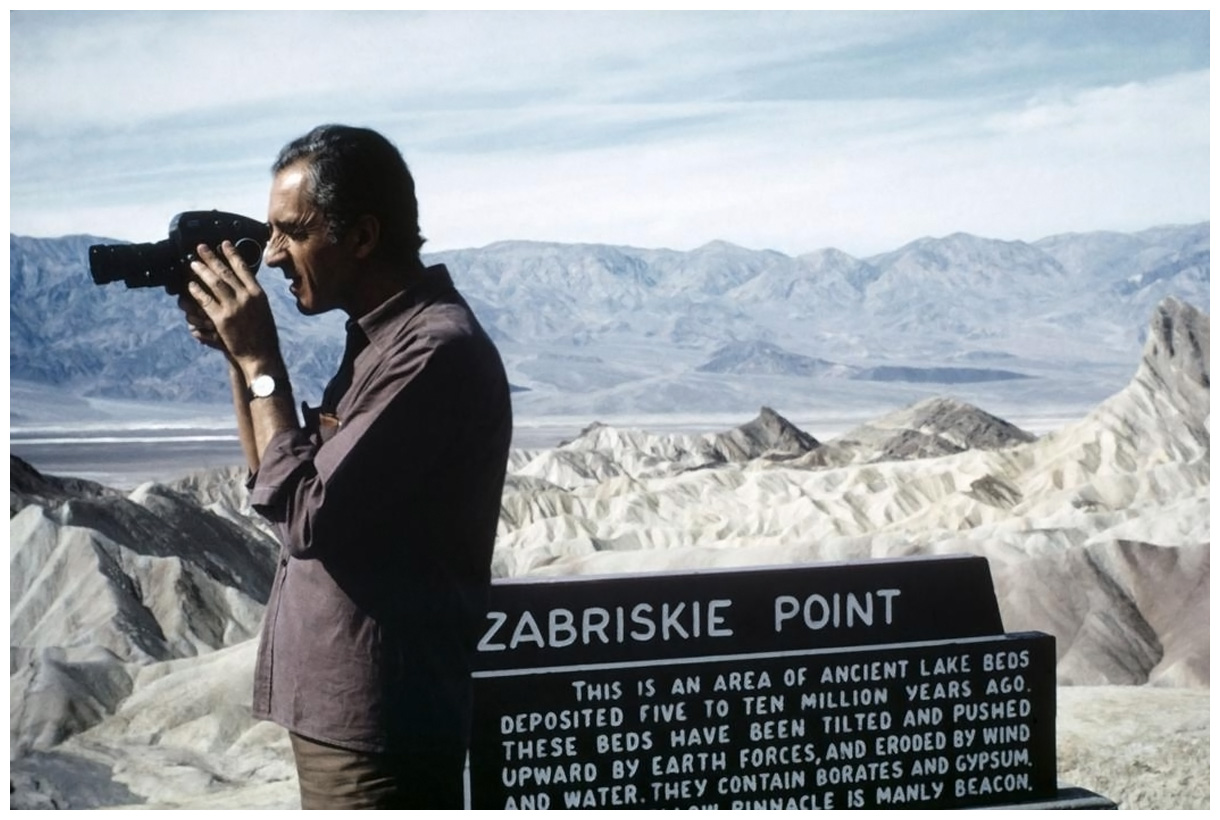

9. Michelangelo Antonioni

Michelangelo Antonioni has certainly contributed a great deal in defining a new language for film and pushing it toward more unconventional visual aesthetics. Much like all the other masters and auteurs on this list, it was a philosophical choice rather than just a stylish one for him, because he simply saw a lot of uncertainty and purposelessness in modern life and chose to create a visual language for it.

Thus, in his films, he started focusing on image and composition instead of character and story. He also used long takes as a cinematic interpretation for lingering on this human condition, and since he believed modern life has alienated men, many of his films are a series of shots or images that seem disconnected at first glance and require the viewer’s attention to their very deliberate compositions and details to understand the mood and ideas behind them.

Through this, Antonioni managed to challenge conventional storytelling and accepted dramatic rules at the time and offered a new radical cinema which of course came at a price. Even film like “L’Avventura” (1960), which won the Cannes Jury prize at the time of its release, was booed by many viewers and it took some years to be accepted as a masterpiece of modern cinema. This film is a part of his famous trilogy on modernity and is followed by “La Notte” (1961), and ”L’Eclisse” (1962), which were also highly acclaimed by famous film festivals and later critics and film buffs internationally.

Antonioni continued to push the boundaries of the film narrative with films such as “Blow-Up” (1966) and “Passenger” (1975) and mastered his unconventional cinematic language. He had a profound influence on the art films and indie filmmakers after him, including Miklós Jancsó, Sofia Coppola and Wim Wenders. The latter one was not only a great admirer of Antonioni but also assisted him on his last film, “Beyond the Clouds” (1996).

10. Andrei Tarkovsky

It’s no coincidence that many great directors on this list are famous for suggesting theories on their cinema, for to create a visual universe of their own, they needed to have a vision and philosophy behind it. Tarkovsky is no exception to this and his works can be recognized by his elaborately designed long takes, nonlinear structure and poetic imagery.

Born to a poet father and having a special interest in spiritual themes, he used his methods and aesthetics to capture dreams, emotions and metaphysical ideas. Famous for highly acclaimed films such as “Andrei Rublev” (1965), “Solaris” (1972), “Mirror” (1975) and “Stalker” (1979), he usually used long takes to capture time as though he was sculpting it. “Sculpting in time” was his film theory to depict his experience and understanding of time and to do so, his films are often composed of several long takes and few cuts to put the audience in a unique experience of time and sensing the moments in his films.

Another notable element of his visual style was his unique use of color; he used different shades of color and black and white in different parts of his films, which was often to divide the films into different chapters or sections thematically or based on its mood, which can be best seen in “Stalker” (1979), for instance.

Tarkovsky’s films are also full of symbolic and religious imagery as well as natural elements, such as water, cloud, rain and reflections, and he often favored surreal imagery to a more familiar reality. Through this language and such elements, he succeeded to create a very personal, self-reflective visual language and express delicate themes such as memory, dreams and nostalgia with his audience.

Ingmar Bergman, another master of modern film grammar, absent on this list, once said about him: “Tarkovsky for me is the greatest (director), the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.”

Author Bio: Ali Mozaffari is an amateur short film maker, film buff and film reviewer who enjoys exploring cinema and the art form. Ali also enjoys photography, exploring new gigs and exhibitions in his spare time.