5. Brazil (1985)

Terry Gilliam perfected the movie mindfuck with his dystopian satire Brazil. This dense, detailed, and visually rich sci-fi fantasy pairs sublimely with a strangely nostalgic retro-future where unexceptional everyman Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) is but a cog in an Orwellian governmental machine.

“[Brazil] is a film that bears watching again and again and again,” says British filmmaker Ben Wheatley (Kill List [2011], Free Fire [2016]), a devotee of the film, adding; “It’s so packed with detail, it’s funny and so political. It’s just a perfect film I think.”

There’s a slapstick quality to Brazil, which was written by Gilliam along with Tom Stoppard and Charles McKeown, and a majestic ambition in its futuristic depiction of bureaucracy gone mad, and for all it’s bizarro visuals––terrorists with baby-faced masks, angelic dream sequences, Lowry’s mother’s endlessly odd facelifts to retain her youth––it’s a film that can be deliberately hard to follow. That doesn’t mean that Brazil isn’t Gilliam’s finest hour, for it certainly is.

The original title for Brazil, according to Gilliam, was 1984½. “Fellini was one of my great gods,” says the director, “and it was 1984, so let’s put them together.” This easily accounts for the arthouse instincts of the film, as well as the surreal and very serrated edge in this playfully pretentious but still remarkably miraculous sortie into the imagination.

4. Withnail and I (1987)

The archetypal British cult film comedy, writer-director Bruce Robinson’s semi-autobiographical eulogy to unemployment and acquaintanceship, Withnail & I, is a tiny tour de force. A mélange of quotable discourse (“We want the finest wines available to humanity, and we want them here, and we want them now!”), not to be forgotten characters (Richard E Grant’s Withnail is absolutely iconic, and Richard Griffiths’ Uncle Monty is divine and pitiably droll), coarse social commentary, and elegant farce, guarantee greatness.

“[Withnail and I] achieves a kind of transcendence in its gloom. It is uncompromisingly, sincerely, itself. It is not a lesson or a lecture, it is funny but in a consistent way that it earns, and it is unforgettably acted,” wrote Roger Ebert in his original and very enthusiastic review of the film, adding; “Bruce Robinson saw such times, survived them and remembers them not with bitterness but fidelity. In Withnail, he creates one of the iconic figures in modern films. Most of us may have known someone like Withnail.”

Set in a dog-eared Camden-Town flat at the ass-end of the 1960s, Withnail & I fixates on two actors on the dole, and their attempts to return to form. Narrated by Marwood, played by Paul McGann, life is anything but biscuits and butter drips. Withnail, a lovable but self-destructive drunk, doesn’t so much buoy his friend, as hold him down. Taking an ill-starred holiday in the country ultimately alienates the pair, but not after many booze-soaked scenarios play out as self-discovery and desolation ooze in.

Numerous drinking games accompany the film, a witness to its prestige. Anyone who’s ever struggled, said goodbye to a friend, or gone on a regrettable drinking binge, can find familiarity with this wonderful, witty, humanly relevant, and near-perfect picture.

3. Phantom of the Paradise (1974)

“Brian De Palma has an original comic temperament; he’s drawn to rabid visual exaggeration and to sophisticated slapstick comedy,” wrote Pauline Kael, adding “[Phantom of the Paradise] is a one-of-a-kind entertainment, with a kinetic, breakneck wit.”

In 1974 Brian De Palma made the ultimate midnight movie, a campy, way over-the-top horror musical that beat the Rocky Horror Picture Show to the punch by a solid year and a half. As a playful piss take on popular music, Phantom of the Paradise nails a lot of the tropes of the era, sending up the Beach Boys, Glam Rock, and a Phil Spector-like impresario named Swan, amongst them. But for all of the film’s flimsy and deliberate B-movie trappings it is a formal showcase of stylish and chic technical bravado and fist-pumping excitement.

Of the film’s numerous and many timeless elements is Paul Williams, absolutely wonderful in the role of Swan, and his superb soundtrack that’s still gobsmackingly brilliant some forty years on. William Finley in the titular role as the cursed Phantom is also a terrible treat, and the fervent cult that has embraced the film have elevated both Finley and Williams to the stature of icons.

“Fox had no idea how to promote [Phantom of the Paradise], because it couldn’t be categorized,” said actor Gerrit Graham (“Beef”) in a recent retrospective interview, adding: “The reason Fox found it unwieldy — the scabrous humor about the music industry, the unhappy love story and the weirdness of some of the characters — are exactly the reasons why people love it now.”

The much ballyhooed New Hollywood of the 1970s sired many enterprising cinematic curiosities but few as exhilarating, outlandish and impressively stylish as Phantom of the Paradise. For all its crackbrained exuberance and frequently hallucinatory tenor, this musical version of Faust is a feast for the senses; silly, exaggerated, and overblown, this is a film that, by midnight movie standards and beyond, is some kind of masterpiece.

2. Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The late, great George Romero’s high concept horror film Night of the Living Dead forever transformed the genre, plucking the narrative away from outmoded Gothic traditions and into the imperative present.

Night of the Living Dead, which was shot on the cheap, opens with a premise that could easily veer into comedy as a brother and sister, Johnny (Russell Streiner) and Barbara Blair (Judith O’Dea) make their annual visit to their father’s grave in rural Pennsylvania and Johnny tries to scare Barbara pretending to be a ghoul with the immortal lines, “They’re coming to get you, Barbara!” But soon the shit and the fan rendezvous with one another as actual ghouls descend upon the pair as they hotfoot it for an abandoned farmhouse to make a stand in. Via emergency broadcasts on TV and radio those taking refuge in the farmhouse slowly piece together what’s happening as the dead rise up on a large scale.

Night of the Living Dead would spawn six sequels –– the best of which, even surpassing the original, has got to be 1978’s Dawn of the Dead –– and countless imitations, as well as establishing a new tradition in zombie mythology.

In Romero’s prophetic picture there are few assurances. The good guys don’t necessarily win, and hope isn’t a guarantee. “My stories are about humans and how they react, or fail to react, or react stupidly,” Romero said. “I’m pointing the finger at us, not at the zombies. I try to respect and sympathize with the zombies as much as possible.”

Oh man, it bites to be us.

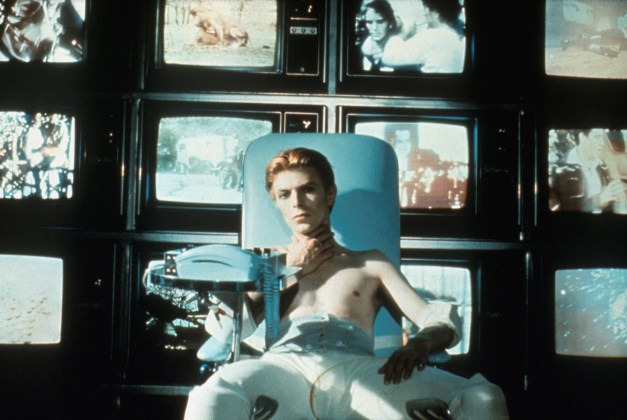

1. The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

With an abundance of unexplained skips in location and chronology and his cheeky trademark sophisticated style, Nicolas Roeg’s adaptation of the 1963 Walter Tevis novel, “The Man Who Fell to Earth” is an ambitious and meditative marvel that was, of course, light years ahead of its time.

Described by Time Out as “the most intellectually provocative genre film of the 1970s,” and starring Thin White Duke-era rock icon David Bowie as Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who’s doomed visit to Earth offers up a multifaceted and ultra-sophisticated inspection of American culture, heartbreak, and homesickness. The film struck a chord with niche audiences, rendering it cult status pretty quickly (prolific sci-fi author Philip K. Dick became particularly smitten with the film, incorporating elements of it and of Bowie’s iconic eminence into his must-read 1981 masterpiece “VALIS”).

Bowie’s character is named for the English scientist Isaac Newton, discoverer of gravity, and as our protagonist in this mind-bending SF masterpiece, he makes discoveries as philosophically and psychologically substantial.

“The story unfolds in a daring sequence of narrative leaps,” writes The Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw in his glowing five star review, adding that the film is “a freaky, compelling concept album of a film.”

Poignant, provocative, and deeply transfixing, genre films are rarely as meaningful, extravagant, or as ambitious as The Man Who Fell to Earth. Populist cinema this most certainly is not, and though at times perhaps indecipherable, Roeg is a satirist and an artist of incredible breadth of view. When was sci-fi ever this iconoclastic and cool and will it ever be again?

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.