6. Shame (2011)

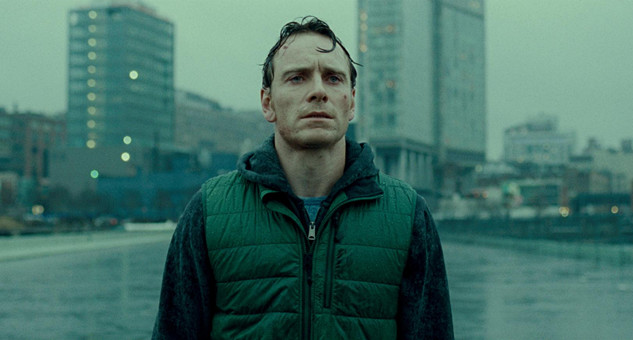

Prior to receiving widespread acclaim and an Oscar for the somewhat overripe ’12 Years a Slave’, Steve McQueen made the superior ‘Shame’, a piercingly honest examination of a successful New York professional struggling with a sex addiction. Elegantly simple in its execution and unflinchingly honest in its exploration of the temptations and urges plaguing Michael Fassbender’s Brandon, ‘Shame’ makes for deeply uncomfortable viewing.

Within the drab world that cinematographer Sean Bobbit has crafted, where every colour seems like a different shade of grey, and the buildings merge with the sky, Brandon moves emotionlessly through his daily routine. We learn little of his character, and the only moments of expression and personality that we are treated to are directly related to his sexual addiction.

The dialogue throughout the film is sparse, with Fassbender’s performance richly textured and nuanced, predominantly communicating through body language and facial expressions. His unhappy existence is challenged yet further by the arrival of his manic sister (Carey Mulligan), who shares a very complicated relationship with her brother, and the extreme elements of their problematic relationship are handled subtly and carefully by McQueen.

A later scene painfully displays the difficulty Brandon has in escaping his addictions, and his inability to connect his emotional feelings with his physical ones. The spiral this sends him into makes for desperately grim and depressing viewing. By the end of the film, we are drained at time spent wallowing in Brandon’s world. Whilst there are hints of redemption, we are in no doubt as to just how deep-rooted his problems are, and just how culpable our isolated modern society is in exacerbating them.

7. Under the Skin (2013)

Right from the opening scene of Jonathan Glazer’s eerie masterpiece ‘Under the Skin’, where we witness what could possibly be the conception and birth of an alien species, its lofty aims are apparent. Its ostensibly incoherent narrative and slow pacing will alienate some viewers (pardon the pun), yet it has much to say on what it is to be human, and the time spent gazing at the world through Scarlett Johansson’s alien lens is utterly mesmerising.

Glazer is richly rewarded for his frequent risk-taking throughout the film, and the comparisons with Kubrick that he has been receiving do not feel unearned. We follow this alien through the streets of Glasgow, as she first tries to make sense of her surroundings, before beginning to prey on the locals.

These sequences, where young men are lured into her black liquid trap, submitting to the voluptuous seductress are extraordinary; erotic and terrifying in equal measure. The casting of Scarlett Johansson is inspired, with it not hard to pick up on the double-meaning of ‘alien’, the Hollywood icon herself looking like she doesn’t belong in the gritty Glasgow landscapes.

The ending is particularly striking, unconcerned with providing straight-forward conclusions, instead allowing the experience to come to a bewildering and emotional end.

Aided by a remarkable score from Mica Levi that seems to have distilled fear and otherworldliness into audio form, and the stellar work of cinematographer Daniel Landin, who manages to depict the landscapes of Scotland as both bleakly real, and yet inescapably extra-terrestrial, ‘Under the Skin’ is a quite singular cinematic experience.

8. Le Jour Se Leve (1939)

By modern day standards, the bleak misery that ‘Le Jour Se Leve’ wallows in is nothing too out-of-the-ordinary, but at the time it was considered ground-breaking enough to be banned by the French State for being ‘too demoralizing’.

Marcel Carne’s trailblazing classic opens with a murder and only gets bleaker from there. Jean Gabin is in particularly captivating form as Francois, a lovelorn foundry worker driven to tragedy by his feelings of despair and betrayal.

After murdering his love rival at the start of the film, Francois barricades himself in his apartment, where the police begin to try to force their way in. Using the then-innovative narrative structure of a series of flashbacks, Carne shows us what has driven Francois to this point of reckless abandon – the breakdown in his relationship with a lover who shares his name.

Exploring themes regarding the vulnerability we display when we open ourselves up to each other, and the macabre fascination and bloodlust the wider media and public has with the crime, ‘Le Jour Se Leve’ is considerably ahead of its time.

Gabin’s depiction of Francois is brilliant, perfectly combining an amiable-yet-rugged exterior with the romantic sensitivity beneath, and this makes his tragic character even more relatable. Whilst the oppressive lighting of cinematographer Philippe Agostini and pessimistic outlook of the plot can be quite joyless, the film has a wistful insightfulness to share on the fragility of the human experience.

9. Irreversible (2002)

Gaspar Noe’s infamous sophomore feature has had its merits questioned ever since its release, being called cruel and unnecessarily graphic, but there is no doubting the film’s overall power and resonance.

The reverse chronology narrative structure throws the audience in at the deep end, and they have barely settled into their seats before being subjected to extremely brutal, violent imagery of a fire extinguisher being crushed into a man’s skull. The structure means that we are shown the conclusion to conflict, and the engulfing rage that sustains it without any context for how it has arisen, which makes for an incredibly disorienting experience.

If this introduction to the broken world of Marcus (Vince Cassel) was tough to endure, it soon gets far worse. The depiction of the hideous rape and beating of Alex (Monica Belluci), the catalyst for all the film’s anger, is exceptionally tough to watch, predominantly due to the unflinching eye of Noe’s camera, which doesn’t move or blink for the near 11-minute scene.

The audience is forced to be distant voyeurs, utterly helpless to change Alex’s fate. Whilst many viewers might find these scenes too much to handle, they will be rewarded if they are able to persevere.

Because, whilst the reverse-chronology heightens the audience’s disturbed feelings during the opening phases, its effect on the second half of the film is strangely uplifting, and even ends on a somewhat optimistic note. Although there is a heartbreakingly fragility to the playful scenes of Marcus and Alex, they serve to lift us out of the depths of depravity and refocus our minds on their feelings for each other.

For whilst it could be argued that the film presents violence as an inevitable consequence of our nature, the final scenes of the film reaffirm our love of life. Noe reminds us of all the beauty that exists in the world, and what a wonder it is that this can grow and flourish when surrounded by such cruelty and barbarity.

10. mother! (2017)

Darren Aronofsky revels in making his films an exhausting exercise in endurance and yet he managed to take this to another level with last year’s opinion-splitting ‘mother!’, a gleefully mad parable about mankind’s destructive impact on the planet.

Jennifer Lawrence gives an immensely committed, physical performance as the titular mother, trying her best to maintain some order and tranquillity in the house that she has helped rebuild for her poet Husband. He (Javier Bardem) is unable – or unwilling – to recognise the discomfort of his wife as he invites an increasing number of strangers into their home.

This leads to rapidly accelerating chaos, and in and amongst the heavy-handed metaphors regarding climate change and the cult of religion, the audience is subjected to a sensory onslaught of distressing sounds and images.

It makes for an intensely stressful experience, as we try to make sense of the escalating bedlam, full of smashing furniture, bloodcurdling screams, tense confrontations and graphic violence. By the point the film slides into outright nightmare territory, the audience is already completely exhausted; their nerves shred. This makes the scenes that follow particularly cruel, subjecting us to levels of violence and trauma that are usually off-limits for filmmakers operating within a broadly mainstream framework.

However, credit must go to Aronofsky for managing to exert some semblance of control on proceedings, and despite the increasingly ludicrous events that are appearing before us, we never lose sight of his artistic vision. As the credits roll, we might not be entirely clear on what exactly we have just seen, but as an overall experience, ‘mother!’s power cannot be denied.

Author Bio: Benjamin Butcher is an Advertising Analyst and occasional film critic from London. He can often be found at the BFI Southbank, catching a film or getting drunk at the bar. Follow him on twitter @BenjaminButcher.