Some directors are fortunate enough to have two films go into production at around the same time or one immediately after the other. Making one good film is challenging enough, but two, back to back? Now that takes some serious focus, a creative spark, and probably a lot of coffee and energy drinks.

Following our actor list with the same theme, we decided to look at directors this time around. Seeing as we included Jake Gyllenhaal in the actor’s list with his appearances in Denis Villeneuve’s “Prisoners” and “Enemy,” we unfairly chose not to include the director here. Because both those films belong to their actor and director and we wanted to sneak another director on this list.

1. Joseph L. Mankiewicz – No Way Out & All About Eve (1950)

Joseph L. Mankiewicz was a master director who had a knack for writing strong scripts with meaty characters and witty dialogue. He could get career-best performances from his actors and won four Oscars for writing and directing in 1949 and 1950. The late 1940s and early 1950s saw his career as a director peak after years spent working as a screenwriter. He was an all-around filmmaker who made some classic films for Fox.

“No Way Out” saw the legendary Sidney Poitier make his film debut as a black intern at a hospital. When a thief on whom he administered a spinal tap dies in the prison ward, the thief’s hot-headed and racist brother claims it was murder and racial tensions soar.

Notable for being one of the first films that gave African-Americans the same equal standing as its white characters and actors, it features none of the clichéd characters Hollywood usually gave black actors in their misguided, exploitive and stereotypical films on racism.

While some of the way Mankiewicz’s script handles story beats and monologues are very much dated, especially the typical conclusion where a black person does something good for the white racist, changing him to see blacks as a regular people. However, aside from some of these flaws, “No Way Out” is a refreshing and engaging film.

“All About Eve” is perhaps Mankiewicz’s most known and renowned film. Set in the world of theatre, Anne Baxter plays Eve Harrington, a young and eager fan who worms her way into the life of an aging star, played by Bette Davis. Pretty soon Eve is threatening to take over the star’s career and personal relationships. She’s a master manipulator who is dangerous because she seems so innocent. She wants to be a star herself and will do whatever it takes to achieve it.

Mankiewicz’s script is filled with memorable characters and dialogue and is quite simply one of the best scripts ever written. The actors take full advantage of the rich material that saw the picture nominated for five acting Oscars, four of which were in the actress category. And with a tight script, everything else falls nicely into place.

2. Alfred Hitchcock – Dial M for Murder & Rear Window (1954)

The Master of Suspense made enough films to fill the careers of three directors. The 1950s were Alfred Hitchcock at his supreme best, as he kept knocking out one hit after the other. With “Dial M for Murder” and “Rear Window,” he released two intimate looks on murder from different perspectives.

“Dial M for Murder” is based on a stage play by Frederick Knott about a married couple who live together in a London apartment. The wife has been having an affair for some time, and although the husband knows, he hasn’t said anything, because he’s been secretly thinking of a way to murder her and eventually comes up with a plan that involves a friend and a telephone call. But murder wouldn’t be much fun if everything went according to plan.

Regarded as one the best uses of 3D from that era, the murder mystery is business as usual for Hitchcock. It has a tight and unpredictable plot with his visual flair and suspense that entertains more with suggestion. It’s the classic tale of murdering the one you love (or used to love) and trying to not get caught.

The classic “Rear Window” offers us an outside look at murder in the form of voyeurism. Confined to his New York apartment with a broken leg, a photographer kills time by spying on his eccentric neighbours from his window. His imagination and paranoia gets the best of him when one of these neighbours disappears and her husband seems to have something to do with it. With Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly playing the leads, you know you have a winner.

“Rear Window” is simply the reason why they call Hitchcock the Master of Suspense. He’s no stranger to making larger-than-life films that take place in a contained environment. Just like “Dial M for Murder,” limited locations bear no factor in the entertainment. We’re right there with his characters, experiencing every little thought, hesitation and fear. “Rear Window” is a classic film that sits right at the top of his filmography.

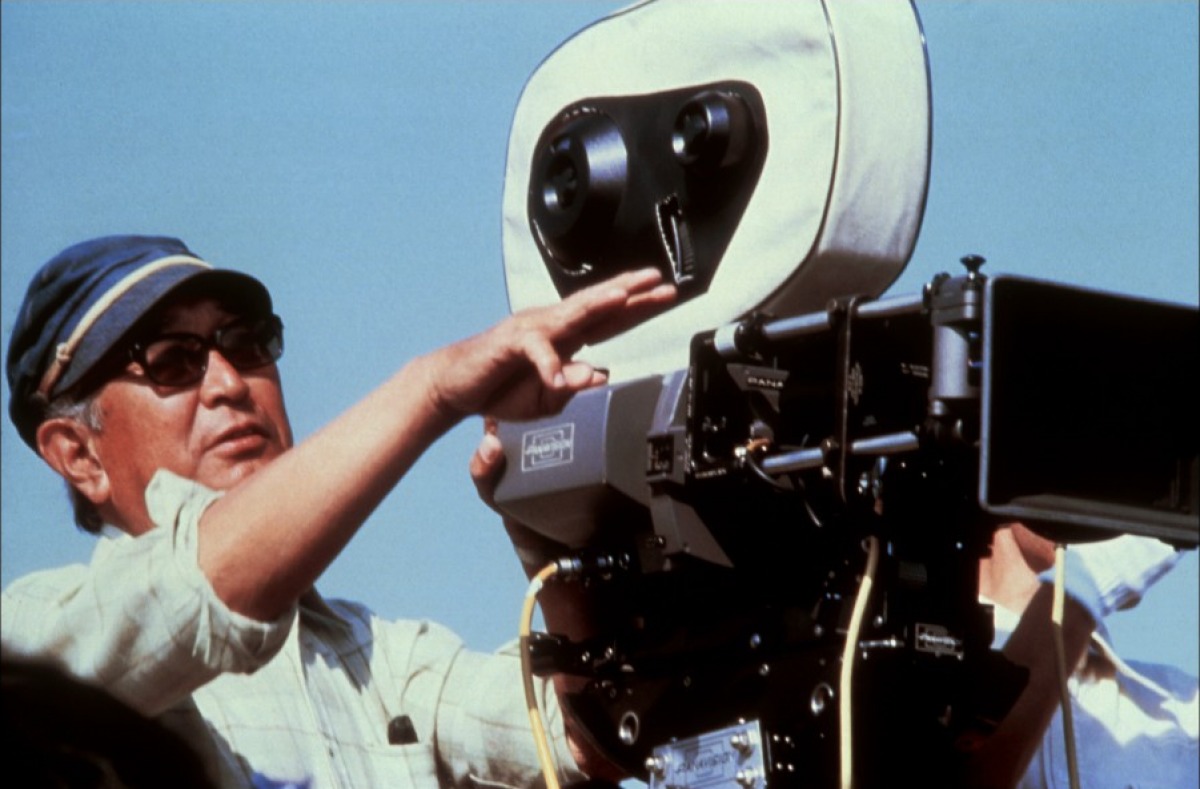

3. Akira Kurosawa – Throne of Blood & The Lower Depths (1957)

Akira Kurosawa was one of the most prolific directors who ever lived. There were a few years where he released two films in the same year: 1949 and 1950 saw the release of “The Quiet Duel” and “Stray Dog,” then “Scandal” and “Rashomon.” As great as those years were, we chose 1957 because the director chose to make two adaptations and succeeded at both.

“Throne of Blood” is a Shakespearean adaptation of “Macbeth,” moving the setting from foggy medieval Scotland to foggy feudal Japan. The great and frequent Kurosawa leading man Toshiro Mifune plays a loyal vassal who is urged by his ambitious wife to assassinate his sovereign after a spirit told him he’ll be rewarded with a castle. Kurosawa takes many liberties, but those same liberties make it one of the best film adaptations of this much-loved tale.

The political and cultural setting makes an interesting watch in what many scholars think is one of the best Shakespeare adaptations ever made. As usual, Mifune is amazing to watch, and is one of the greatest actors ever. And Kurosawa’s direction, editing and cinematography make for one entertaining and expertly-made picture.

“The Lower Depths” had Kurosawa continuing his romanticism with Western literature and stage plays. This underseen film is based on the play by Maxim Gorky about a slum flophouse of eccentric characters. Mifune plays a thief who ends his relationship with the landlord’s wife in favor of her abused sister. The action stays in one location in what seems like a shack in a garbage pit in which the characters describe as hell. There are no central characters, as we follow a multitude of characters and storylines.

While regarded as a minor work due to its limited scope, “The Lower Depths” is an interesting film about poverty and the poor. It features some Kurosawa regulars who present the picture with some humor and drama in the misery of poverty.

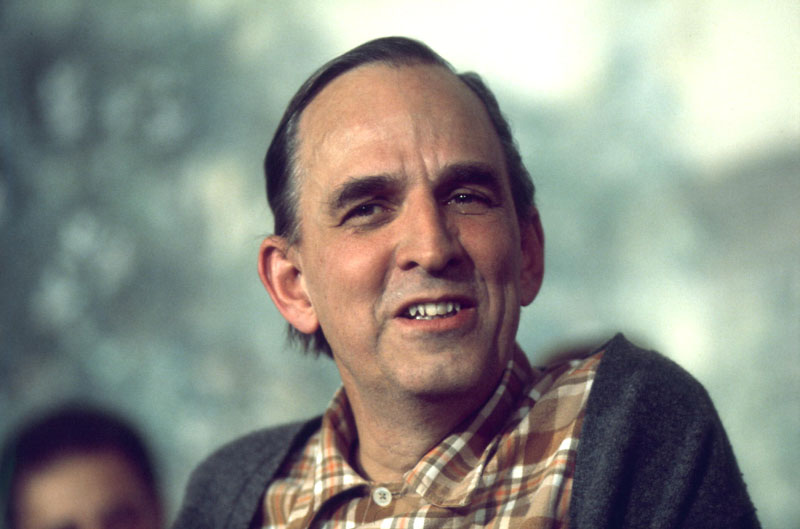

4. Ingmar Bergman – The Seventh Seal & Wild Strawberries (1957)

The year 1957 saw the release of two wildly different Ingmar Bergman films that are viewed in equal measure as classics. Both films share some of the same cast and crew made up of Bergman regulars. Although different on the surface, “The Seventh Seal” and “Wild Strawberries” deal with similar but contrasting themes of death.

“The Seventh Seal” follows the journey of a medieval knight and his trusty squire during the black plague in Denmark. As they journey through the country, they see the bleakest and darkest aspects of death. It’s something to be feared as madness and hysteria take hold of people who turn to religion for answers. Death is personified here by actor Bengt Ekerot through some iconic imagery in a chess game with Max von Sydow’s disillusioned knight. The film is really about mortality and the uncertainty of religion and the afterlife and how different people deal with such questions.

“Wild Strawberries” follows an old professor who looks back on his life while on a road trip to receive a degree for his long career in bacteriology. The themes of death here are more graceful, nostalgic, tender and accepting. As the old man (played beautifully by Victor Sjöström) comes to terms with the final stages of his life, he looks back at past moments of his life that are tinged with regret and longing. The moments that made him who he is and how he passed on his worst traits to his son. It’s undoubtedly Bergman’s most touching picture and perhaps his most beautiful.

Both films cemented Bergman’s reputation to an international audience as a director of note. They showed his skill at working cheaply and quickly without sacrificing any of his artistic vision and sensibilities. His mastery of the craft and philosophical tendencies insured that both films and their director would live on for years to come.

5. Francis Ford Coppola – The Conversation & The Godfather Part II (1974)

Has any director been blessed with such an amazing year as Francis Ford Coppola in 1974? He released two films that went on to become classics, one winning him the Grand Prix du Festival (Palme d’Or) at Cannes and the other Best Picture at the Academy Awards. Coppola was definitely riding high in a year that saw him tower over the industry like so many of his iconic characters.

“The Conversation” stars a never-better Gene Hackman as a surveillance expert who falls into the depths of paranoia and moral dilemma when his tapes reveal more than he wishes they had. Ironically arriving at a time when U.S. security and surveillance worries were on everyone’s mind, the film captured the fears and paranoia of the time.

While not a box office hit like the two Godfather pictures, “The Conversation” is just as well a masterpiece like those two. It fires on all cylinders, from Hackman’s fiery performance as a tragic loner who lives for the job, Coppola’s tight direction, to the framing and sound design that echoes like surveillance tapes at times. It’s a personal but in no way a minor work.

With “The Godfather Part II,” Coppola upped the ante in every single way. The longer runtime, the two timelines, two of the best actors of the time, and in all accounts he succeeded well and beyond. We see an epic telling of the beginning of a crime dynasty and its possible downfall through father and son. And this all works because of the maestro behind the camera and his insane ambitions and talents. Cleaning up at the Oscars with a Best Picture win, Coppola proved that sequels can be bigger, bolder, broader, and most importantly, better if not just as good.