5. Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

“The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” is an American horror classic. It genuinely frightened many people upon its release, and still holds up today as a monument of the macabre. Isn’t it a highly violent film, though? Hasn’t it warped countless minds? Doesn’t it promote violence, especially against women? Well, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Some say the meat hook scene emphasizes violence against women, and they’ll note how Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) faced more violence than others characters. Still, it’s not entirely true that “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” promotes violence as something attractive or appealing.

If anything, the movie makes violence look awful, nightmarish, unappealing. The villainous family is full of unattractive freaks, misfits, cannibals, loons. It’s not particularly sexy. Horror fans might even find them funny, but any “normal” person won’t likely watch this and think, “Gee, I’d better get out there and do that!”

Nevertheless, for quite some time, the British Board of Film Classification refused certification for the uncut theatrical version, and a home video release. Why? The aforementioned moral panic surrounding “video nasties,” of course! In other words, if some young Brit saw Leatherface, he might have donned a mask of human flesh, found a light weight chainsaw and re-decorated his bedroom with meat hooks, human lampshades and animal bones. It would require a lot of time and effort, but would it ever be worth it!

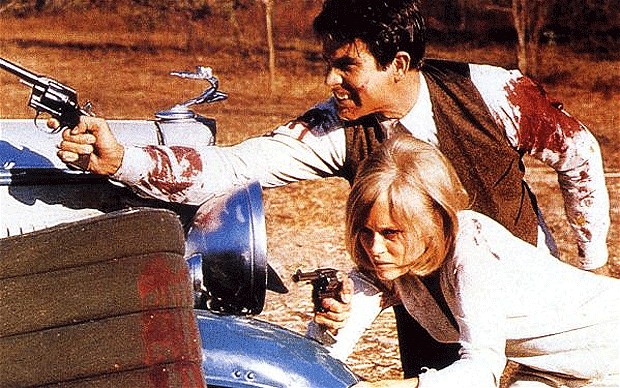

4. Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, “Bonnie and Clyde” is a 1967 biographical crime film about Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker. While many loved the movie and it’s considered a classic, some were upset by it, feeling it glorified violence.

As a stellar example, Bosley Crowther of The New York Times used it as his reason to campaign against violence in American films. Interestingly, it backfired. The New York Times actually fired Bosley Crowther for being out of touch for his critique (which surely made him an even big fan of the film).

Many say “Bonnie and Clyde” inspired violence in American cinema, but that’s sort of an old line. Such claims are typically made by people trying to scapegoat media for societal violence, as sort of a convenient explanation.

Also, quite often violence in society is overblown. The fact is, “Bonnie and Clyde” weren’t fascinating because of how common they were, but due to how rare and enigmatic they seemed. Even their names — Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker — carry a certain style with them, like they were tailor-made for stardom.

Also, “Bonnie and Clyde” doesn’t even depict the two as entirely cool characters. Instead, they are shown as imperfect human beings with their own quirks, and they were not invincible to bullets. Also, aren’t there possible morals to their violent ending, regardless of how it’s stylized on film? The two criminals really did die, and the film depicted their deaths at least somewhat realistically. One wonders just what the Bosley Crowthers of the world expect…well, not really.

3. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

There’s no mistaking it: “A Clockwork Orange” actually is an offensive movie. However, that is exactly how it’s intended. Shock cinema existed before the 1970s, but that decade ushered in a new movement to merge the shocks with heightened style, and to combine them with conflicting moral messages. The point wasn’t just to offend, but to offer complex messages about life which are difficult to explain through conventional language. Or, at least this is how I would defend “A Clockwork Orange.”

Another defense would be for a person to actually watch it and ask, “What was Stanley Kubrick trying to do here?” The answer could be different each time one watches it, or at least should be. The fact is, there are so many different layers to “A Clockwork Orange” that conventional moralizing just won’t do in encapsulating its meanings. It’s not for the faint of heart, but even less so for the faint of mind.

Still, some tried to regard it simply as immoral, degrading smut. For example, Pauline Kael of the New Yorker called it pornographic. She said it “dehumanised” Alex’s victims, and that “the victims of the thugs” are “more repulsive and contemptible than the thugs” themselves.

Kael called Kubrick a “bad pornographer” for the rape scenes. Of course, men are also degraded by the thugs, but that fact is predictably swept under the carpet. So is the fact that Alex’s buddies aren’t really depicted as good people, or made out to be entirely cool. They think they are, and that’s a huge part of the movie’s power. These characters think they can do what they want, and violence is normal to them. (SOURCE: http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/0051.html)

Also, regarding the “dehumanizing” critique, one could easily note that film itself doesn’t really do that. In many ways, it is the viewer’s decision to interpret something that way. At no point is a character in “A Clockwork Orange” truly non-human. They are simply treated that way, which is an illusion that Kubrick actually seems to exaggerate, to make us examine this phenomenon in our own minds. Maybe it’s not a successful trick for everyone, and maybe “A Clockwork Orange” fails for some, but for others it has become a classic precisely for its depiction of an immoral/amoral society.

Some blamed “A Clockwork Orange” for some crimes, with the standard refusal to consider alternate explanations (or the fact that one could watch the film without becoming violent). Because of moral panics, the movie initially carried an X rating in America, and was fairly rare in the UK for the longest time, too. Of course, if anything, declaring something racy might only increase its allure, as being something “they don’t want you to see!” It’s funny how censors are so slow to pick up on that, though it’s sort of an obvious truth. It’s almost like they’re not thinking enough about what they’re doing.

2. Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood (1988)

Oddly enough, one of the most attacked movies on this list is a Friday the 13th movie. However, it wasn’t just attacked in the usual way, where critics lambasted it and certain groups treated it as cancerous. No, this movie was very heavily censored, and boy does it show!

While a lot of movies still retain a fair amount of gore (because that’s sort of what you expect), “Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood” was all but totally rendered a “blood-free zone.” Sure, there’s a spatter of it here and there, but I’ll put it this way: The censors almost did more hacking and slashing to this movie than Jason himself!

What’s missing? One character originally had a sickle go through her neck. Gone! One originally had his head crushed. Not anymore! A party hat lodged into one’s eye with excruciating detail? Nope! How about an annoying character’s head cut in half, so we could see her eyes cartoonishly wriggle in their sockets? None of that, either! It was all chopped out to avoid an “X” rating (which sounds much cooler than NC-17 anyway).

While Friday fans can still enjoy Part 7, the real casualty here is the gore. Without that, “The New Blood” plays more like a made-for-TV melodrama which, for some reason, has Jason Voorhees fighting some telekinetic chick. This is one case where more gore would have improved the picture. You can still watch the deleted scenes, but they now lack sound (and fury).

1. The Great Train Robbery (1903)

One of the first silent films, Edwin S. Porter’s “The Great Train Robbery” is also one of the first violent films. It’s also undeniably a classic. Ironically, though, it almost doesn’t belong on this list. At the time it was released, there was apparently no moral outrage.

Still, it depicts a man bludgeoned to death by a piece of coal, and a criminal gang that shows no mercy toward the innocent. It’s exactly the kind of thing concerned parents groups and censors go after. The only reason they haven’t is that it’s such an old movie, and a Western.

It also has a famous scene where the lead robber, played by Justus D. Barnes, shoots directly at the camera. Supposedly, viewers who watched this ducked and screamed, before remembering it’s just a movie. According to film historian Charles Musser, “The shot added realism to the film by intensifying the spectators’ identification with the victimized travelers.” The scene has been duplicated by Martin Scorsese’s “Goodfellas” and a major episode of the TV series Breaking Bad.