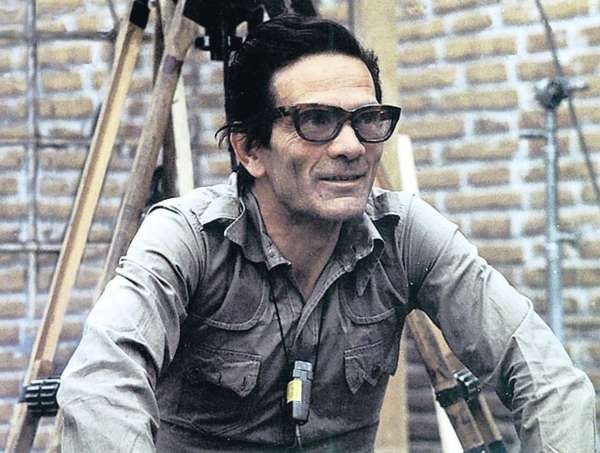

5. Pier Paolo Pasolini (Italy)

When thinking about Pier Paolo Pasolini, we’re not mistaken if we think he was one of the most challenging, important, and controversial Italian director due to his works on sexual matters and religion.

According to American film critic Roger Ebert, Pasolini’s “The Gospel According to St. Matthew” (1964), “[…] one of the most effective films on a religious theme I have ever seen, perhaps because it was made by a non-believer who did not preach, glorify, underline, sentimentalize or romanticize his famous story, but tried his best to simply record it.” Regarding his personal life, his open homosexuality and support on Vatican’s views on abortion caused him his permanent exclusion from the Italian Communist Party.

Now, let’s get straight to the point, and that is one of the most controversial and uncomfortable films to watch, Pasolini’s final work “Salò le 120 giornate di Sodoma” (“Salo, or The 120 Days of Sodom,” 1975). This film was not only banned in Italy but also in several countries since its release. “Salò” recreates the four protagonists of Sade’s novel, representing the church and the authority under fascist era of Benito Mussolini.

According to the director, “The real meaning of the sex in my film is as a metaphor for the relationship between power and its subjects.” This film was briefly ran in theatres in Italy after being banned in 1976 due to its graphic violence, sexual deviance, and brutal murder. It was banned in Italy due to the depictions of sadism, which provoked violently denunciatory reactions from the church and cultural critics.

4. Sergei Parajanov (Ukraine)

The poetic Soviet filmmaker Sergei Parajanov made the most remarkable and stunning films between the 1950s and the 1990s, a period of time in which censorship was a commonplace since the U.S.S.R. was only interested in socialist realism, an imposed style by the government that glorified the values of communism.

If you’ve already watched any Parajanov’s film, you can clearly see that Parajanov was not interested in talking about the grandeur of the Soviet Union. He belonged to the Ukrainian poetic school, and many of the members had several problems, not only with the Party administrators who did all they could in order to make their films have limited distribution, but also with the problem of winding up being banned.

For Parajanov, it was much worse than being banned: he was blacklisted from Soviet cinema and was forced to live in exile. One of his most famous films, “Tini zabutykh predkiv” (1965, “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors”), which earned him international admiration for its use of color and costume, was banned and the director was forced to leave the republic permanently in the early ‘70s, although it was praised by some Party officials in the Soviet Union.

Vitaly Nikitchenko, the chair of the KGB in Ukraine, had sent a report in 1969 to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine advising of Parajanov’s “negative influence on the fostering of young creative workers.”

In 1973, Parajanov was arrested by the Ukrainian KGB on charges of rape, homosexuality, and bribery and claiming that the director kept “meetings and correspondence with foreigners from capitalist countries,” which could be regarded as treason to the Soviet Union.

He was imprisoned until 1977, but even after his release, he was persona non grata in Soviet cinema. It was not until the 1980s when he could resume his work as director. However, life in labor camps and in prison has weakened physically and mentally one of the greatest director of the 20th century.

3. Dušan Makavejev (Kingdom of Yugoslavia, now Serbia)

Makavejev was undoubtedly an authentic pioneer in Yugoslav during the 1960s and early 1970s, the so-called Black Wave. This film movement was characterized by its non-traditional approach to filmmaking, gallows humour, and the critical examination of the Yugoslav society at that time.

It was a period of intense creativity in which directors let their imaginations run wild in order to show the human psyche and to openly criticize the socialist government. The liberalization of the film form subsequently brought attacks on the movement that led to the banning of several films, and some directors were forced to live in exile.

In 1971, Makavejev’s “WR: Misterije organizma” (“Mysteries of the Organism”) was internationally acclaimed. However, in Yugoslavia, it was quite a different story; the Yugoslav Ministry of Culture “shelved” this films due to its sexual content, which makes nonconformist political statements. “WR” was shown at Yugoslav Film Festival in Pula, but it was later withheld from distribution after Soviet pressure.

A lawsuit was launched against Makavejev by the veterans’ association in Vojvodina. This powerful opposition made Makavejev travel abroad since his further projects weren’t supported, but in the West he only managed to realize six films since he hasn’t been able to find the necessary help to carry through all the projects he wanted.

In Derek Jones’ Censorship: A World Encyclopedia (2001), the author claims that Makavejev “experienced two types of censorship—the repressive censorship of communism and the subtle one of capitalism. Under communism he made films which were later shelved; under capitalism nothing was shelved, but many of his projects never materialized.”

2. Fritz Lang (Germany)

Lang has been considered by many to be one of the greatest German and Hollywood directors, whose characteristic epic and dark films are distinguished by their intense visual style and expressionist lighting techniques with highly geometric compositions.

In this case, the director was not only censored in the first place by Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda of Nazi Germany, who decided to ban Lang’s “Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse” (“The Testament of Dr. Mabuse,” 1933), since it could “undermine the audience’s confidence in its statesmen,” but he was also “asked” to cooperate with the Nazi Party, an offer that he decided to turn down. Lang’s case was a matter of life and death; it wasn’t his work that was in danger, but his life.

Everything starts with the above-mentioned film, which subtly criticized the Nazi Party, making Mabuse an allegory of Hitler. The Nazi Party confiscated the film. However, Lang didn’t give up. He received a letter to meet Goebbels to talk about this film. When he met Goebbels, he admitted to Lang that Hitler claimed that he was the one who would “make the national socialist films.” Lang deceived Goebbels and ended up working in Hollywood.

Lang was forced into exile and it was there where he was able to be free, so he started to make anti-Nazi films such as “Hangmen Also Die!” (1943) and “Ministry of Fear” (1944), films in order to educate people about fascism.

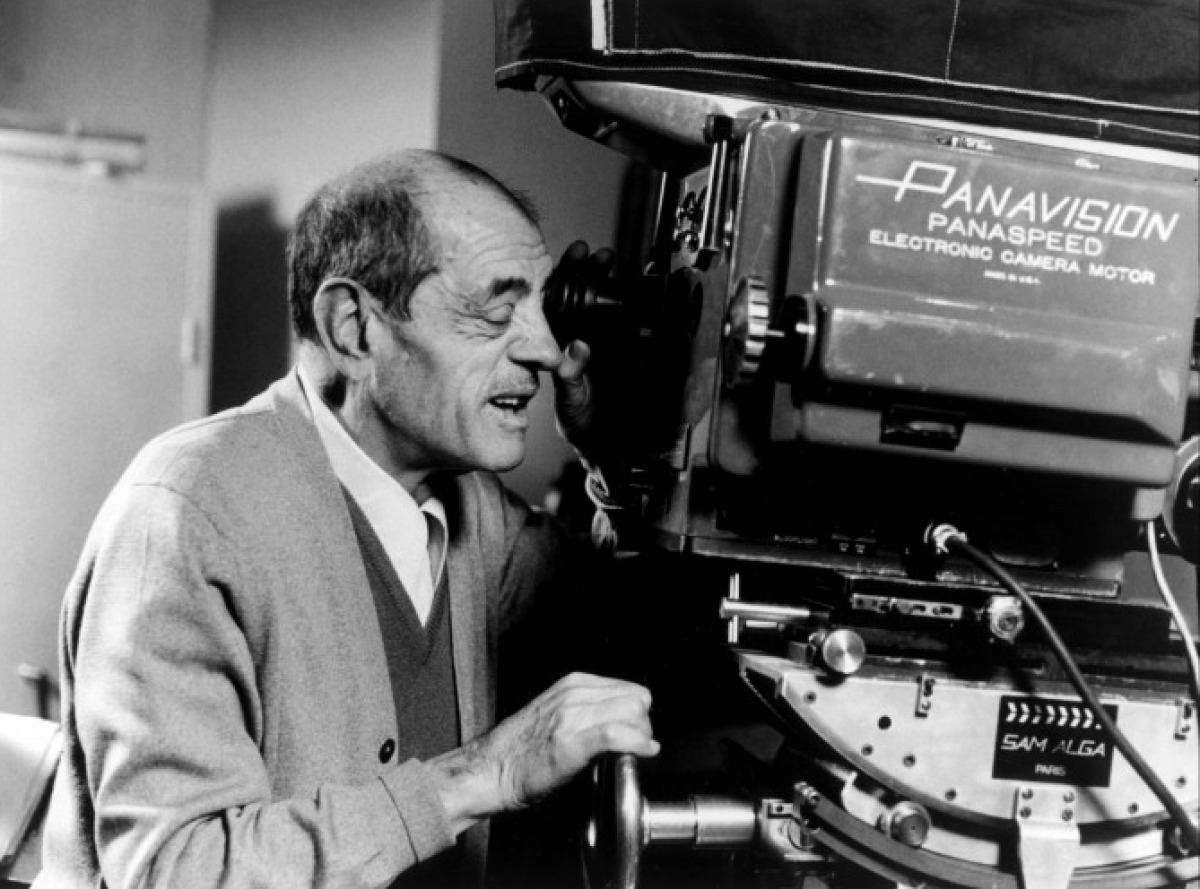

1. Luis Buñuel (Spain)

The censorship Luis Buñuel suffered didn’t begin in his home country, but in France when “Un Chien Andalou” (1930) was confiscated by French authorities; this was clear proof that the new revolutionary surrealist cinema the director wanted to make wasn’t for everyone.

Back in Spain in 1935, a large number of artists such as Rafael Alberti, María Zambrano, Luis Cernuda and Luis Buñuel founded the Alianza de Intelectuales Antifascistas (Alliance of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals), which was in charge of writing manifests attacking fascism and holding meetings to fight fascism back from a cultural point.

A year later, the Spanish Civil War ended, and Spain was completely destroyed. It was a country sunk in misery, poverty, and repression. Months before finishing the war, he was asked to go to the United States in order to work in the MoMA, but he ended up in Mexico since, in the US, he was considered to be a persona non grata due to Dali’s comments on Buñuel’s political views.

In Mexico, Buñuel worked with many Spaniards who were in exile such as Luis Alcoriza, Max Aub, Juan Larrea and Rodolfo Halffter. In 1950, the director went to France in order to attend the release of “Los olvidados” (“The Young and the Damned,” 1950), so he took this chance to meet again with his family.

It was in 1960 when Buñuel dodged the Spanish authorities by returning to Spain in order to film “Viridiana” (1961) saying to the government that he was going to film a Mexican soap opera, but this was not so. “Viridiana” was banned outright in Spain since it was a film that criticized the Catholic Church, the same Catholic Church that supported Franco.

Finally, two years after Franco’s death, when Buñuel was 77 years old, “Viridiana” was released in Spain. Many were happy of having Buñuel’s films in Spain, since he was one the greatest Spanish director who was banned in Francoist Spain.