Horror cinema is currently undergoing a resurgence. Acclaimed films of the decade such as Jordan Peele’s critical-darling Get Out and Ben Wheatley’s genre-hybrid Kill List have shown audiences that horror can be given new life if experimented with.

While much of the genre’s output remains rather dull and uninspired, since the turn of the century, audiences who have taken the time to discover possible hidden gems have been rewarded with a number of great and interesting horror films. This list hopes to raise awareness of some of these films, in hopes that they receive more appreciation and attention.

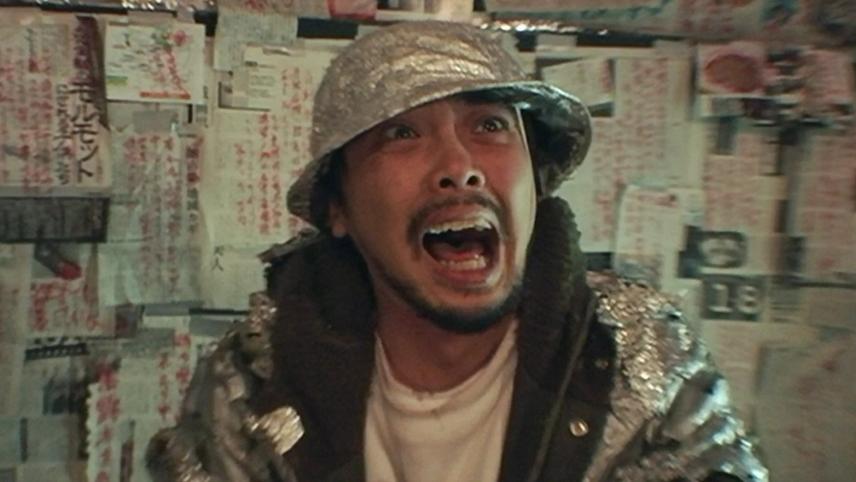

10. Noroi: The Curse (Koji Shiraishi, 2005, Japan)

Koji Shiraishi’s second feature-film was a welcome addition to the saturated Japanese horror genre at the time of its release. The filmmaker has now become more renowned for dwelling on the torture-porn sub-genre with films such as 2009’s Grotesque, which the BBFC rejected for release in the UK, and of course, the totally abysmal face-off flick, Sadako vs. Kayako.

These directorial credits certainly do no favours when introducing this entry, and yet, their existence fails to dampen this early career-achievement, of which is a complicatedly structured found-footage faux documentary that Shiraishi would later try to emulate with films such as 2009’s Occult, but with less success.

The film takes us on the journey of Masafumi Kobayashi (Jin Muraki), a journalist dedicated to exploring supernatural phenomena. He began compiling his enquiries of paranormal mysteries onto videotapes, and in 2004, made his last: The Curse. On April 12, his house was burnt to the ground, with his wife found in the remains, and Kobayashi declared missing, never to be found. This film is an exhibition of the documentarians final project.

Perhaps most unusual about Shiraishi’s film is how complex and convoluted its narrative becomes as Kobayashi becomes further ensnared in this puzzling and ominous case. It was fairly unconventional for Japanese horror cinema at this time to have such a large cast and to push the two-hour duration mark.

Evidently, there was no shortage of footage, and the director’s ambition was surely validated, because the final film feels like the work of someone intent on realising their vision, taking no notice of anyone restricting it for commercial intent.

There is a lot to take on board narratively – and as with a real case – there are many detours and deviations, which work in the film’s favour, emulating a real case for the audience to engage with as it progresses into darker territory. By encouraging such high-levels of involvement, we are able to become so absorbed in the investigation that the frightening moments feel threatening to us, because Shiraishi’s methods ensure that when Kobayashi feels endangered, we do too.

9. Antiviral (Brandon Cronenberg, 2012, Canada)

When the son of Canadian body-horror maestro David Cronenberg released his feature debut back in 2012, it truly felt like the torch has been passed. The turn of the century seemed to signal a departure from genre-filmmaking; after Existenz in 1999 – a somewhat lesser reevaluation of the themes of Videodrome – the controversial and acclaimed mind behind such great works as The Brood and Naked Lunch turned to more serious crime-drama films with A History of Violence and Eastern Promises, proving just how versatile and skilled a filmmaker he could be.

The release of Maps to the Stars in 2014 showed him to be capable of further twisted social commentary, and for those desperate for another Cronenbergian horror film, his son had them covered with the sadly overlooked Antiviral, an original premise, and yet, still a stylistically indebted love-letter to the films of his father.

Caleb Landry Jones delivers a career-best performance as Syd March, a salesman who provides obsessive fans with the illnesses of their favourite celebrities. His attempts to exploit the agency he works for go disastrously wrong when he finds himself the host of a sought-after illness in the wake of a demanded celebrity’s demise.

The film was criticised by many as a lousy imitation of his father’s early efforts, and the fact that Brandon Cronenberg showed great ability as both a writer and director was unfortunately ignored by the majority.

Although the idea is undeniably the sort that his father would have explored early in his career, it is Brandon’s film and works because of his understanding of modern culture and the extent to which obsession has come to be facilitated in strange and bizarre new ways.

Antiviral feels less a carbon-copy and more a knowledgeable continuation, exploring the concerns his father had and how the advancement of the media has influenced and changed these ideas. It’s spiritually indebted, but in itself, such a unique and intelligent piece of work that many more horror fans should see.

Themes of obsession, celebrity and addiction are singularly explored, and B. Cronenberg’s execution of a fairly distinct visual style was enough to leave potential fans with the promise of much more from the emerging director.

Antiviral is currently the only finished feature to his credit, but fortunately, his new film Possessor is currently in pre-production stages, and sounds every bit as socially-conscious and twisted as his debut. If it’s successful, he’ll be sure to follow in his father’s footsteps as a body-horror master; there’s a long way to go just yet.

8. Over Your Dead Body (Takashi Miike, 2014, Japan)

Even the most dedicated of Takashi Miike fans will admit that the director’s output varies drastically in quality, and with the release of his 100th feature film last year, the well-received Blade of the Immortal, it’s easy to see why being consistent across such an extensive output would be challenging. Regrettably, the bombardment of Miike titles results in many who have enjoyed some of his previous efforts to miss out on the rare gems he continues to craft, and Over Your Dead Body is one of those gems.

Although it remains very underseen, it has received worthy praise; the film won Miike awards for Best Film and Best Director at 2015’s Frightfest Festival, the UK’s largest international genre film festival, and was praised by critic and author Kim Newman as being “astonishingly brilliant”.

The prolific filmmaker’s return to horror centred around a stage incarnation of Yotsuya Kaidan, perhaps the most famous Japanese ghost-story, which has been adapted for film on over thirty separate occasions. Miyuki (Ko Shibasaki) is given the lead role, and is able to pull strings to ensure that her lover, Kosuke (Ebizo Ichikawa) is cast alongside her, and life on stage begins to blur with the reality of their emotions, resulting in grave supernatural consequences.

Miike’s approach to the classic tale is wonderfully modern, and he truly breathes new life into a story written way back in 1825 as a kabuki play by Tsuruya Nanboku IV, while still remaining respectful of its narrative heritage.

It’s a very reassuring effort from Miike, perhaps signalling that his talent and passion for horror cinema has yet to dwindle after all – providing audiences with a disturbingly creative finale and enough twists and turns to leave us satisfied, however, still desiring yet another showcase of subversive scares in the vein of Audition, and the ghastly shocks of Gozu.

Over Your Dead Body is definitely a solid entry into Miike’s catalogue, although, perhaps most exciting is what it represents; if the Japanese provocateur found himself dedicated enough to a terrifying concept, the talent is still there, and audiences could perhaps see Miike turn out another modern-horror classic, just as he did in 1999.

7. Rabies (Aharon Keshales/Navot Papushado, 2010, Israel)

Thanks to significant acknowledgement from none other than Quentin Tarantino, Aharon Keshales’ and Navot Papushado’s second collaborative feature, Big Bad Wolves, received more attention from film fans than expected.

The film was entertaining, gripping, and darkly comic, with many finding it to be an unexpected favourite of 2013. For those who had seen their feature-debut, Rabies, it wasn’t unexpected at all, and was simply further confirmation that the Israeli directorial duo are set to make a grand impression before the decade comes to an end.

Their first film is a comical and inventive feature which manipulates genre conventions to upturn expectations and confront the workings of a genre that it is successfully able to both poke fun at and operate within. Different parties all fall conflict to one another in the woods, with siblings, a group of teenagers, police, a park ranger, and a serial killer attempting to figure out what exactly is going on. The pair’s knowledge of slasher films is complemented by their incendiary approach towards the tropes and drollery of the sub-genre.

Cliches are firmly in place only to debase in hilarious fashion, and as the film finishes, it becomes obvious that this is unlike any other horror film of recent years, although perhaps comparisons can be made with Drew Goddard’s The Cabin in the Woods, as both are revisionist in their approach to horror filmmaking, while at the same time embodying what makes the films they comment on so exciting.

Credited as being the first ever Israeli horror film, Rabies remains a game-changer in many ways, and is a must-see for anyone with a passion for self-reflexive cinema. Their upcoming feature, Once Upon A Time in Palestine, is described in it’s IMDb synopsis as “A genre-bending thriller with elements of spaghetti westerns, war movies, romantic comedies and silent movies set in British-rules Palestine in 1946.” If that isn’t enough to intrigue readers, then Rabies certainly will be.

6. The Nightmare (Rodney Ascher, 2015, US)

When discussing horror-films, it is always fitting to include documentaries, and Rodney Ascher’s The Nightmare is arguably the most terrifying since Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing.

Best known for Room 237 – which explores the obsessive fan theories of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining – Ascher’s interest in those obsessed with horror turns to those burdened by real-life horrors. His 2015 effort delves into the lives of those who suffer from sleep paralysis, and contains a series of interviews and disturbing dramatisations, visualising the torment that these individuals have claimed to experience.

The conversations with the film’s subjects are insightful and offer an adequate and descriptive account of the visions that plague them while simultaneously between sleep and wakefulness, conscious of “hypnagogic hallucinations” but unable to move or speak.

However, it is the dramatisations of their experiences that make the film so disturbing. The dark figures that are shown to be plaguing the sleepers are only men in morph suits, which shows that horror can be achieved cheaply as long as atmosphere and mood can be formerly achieved.

The sincere approach to investigating the nature of these exposures to night-time intimidation make it more than just a cheap gimmick to assemble a series of scary sequences, and the help and understanding shown for those who suffer from this phenomenon makes for affecting yet melancholic viewing.

The imagery on display shows talent in the realm of horror filmmaking, but for Ascher, it is clear that he finds the real terror in non-fiction storytelling, far from the realm of fantasy and unnervingly closer to home.