Watching movies alone is a timeless practice. For many it can be a time of meditation, reflection, or simply uninhibited amusement. Solitude allows for the most intimate and distinctive viewing experiences as it allows for full immersion into the director’s world, allowing one to notice all the minute nuances of a performance and slights of a filmmaker’s hand that other people just distract from. Just like being alone in a room with a painting, spending such time with a film helps a viewer notice everything special and individual in the piece.

Somewhat like talk therapy, enjoying a good film in alone gives way for deeper, more personal emotions to rise. Be it a response to the family dysfunction in Magnolia or the slow approach of death in Melancholia, being alone lets the viewer explore those feelings in utter peace.

Whether making the trek to a theatre alone or staying in a room of one’s own, here is a selection of films that are best to watch alone.

1. Last Year at Marienbad by Alain Resnais

Simply put, Last Year at Marienbad (1961) is a film about deja-vu, the phenomenon of feeling as though one’s present experiences have occurred before. The entire film has a dreamlike structure that offers little explanation for jumps and lapses in time and setting, making the film so notoriously incomprehensible.

What makes this film so great to watch alone is the sense of intimacy laced throughout, due to solitude and earnestness of the characters within. Their isolation makes perfect sense for a private viewing context, in which the film can receive the attention it deserves.

Set in the beautiful Czech spa town of Marienbad, a historic watering hole for royals and other wealthy patrons, the plot follows a trio of Delphic characters: a man, a woman, and a second man, most likely the woman’s husband.

The first man claims to have met the woman before, in his previous year at Marienbad, and that she told him that she needed to wait a year before committing to him. She denies this, prompting the man to make attempts at recovering her memory, while the second man tries to prove his dominance over the first through games of Nim.

2. Magnolia by Paul Thomas Anderson

Magnolia (1999) is a complicated film. Often hailed as a masterpiece of post-modern cinema, the film is rooted in human dysfunction and flaw. With themes of failure, addiction, greed, family, death, Exodus, and fate, the film paints a cynical portrait of the human condition.

Of all PTA’s works, this one is particularly best digested in solitude for its dark themes and highly reflective nature. Magnolia can be uncomfortable and even awkward at times, but this naturalistic portrayal of its characters is what makes the film so special.

The plot is split into several intertwined narratives of the colourful inhabitants of San Fernando Valley, Los Angeles. Following figures like police officer Jim Kurring; quiz show host Jimmy Gator and his family; producer Earl Partridge, his wife Linda, and his son Frank; and former child prodigy Donnie Smith. Their stories are shown in pieces that slowly come together over the course of the film, comprising to form an epic tale.

3. Three Colours Trilogy by Krzysztof Kieslowski

There are a million reasons to adore the Three Colours (1993-94) and a million more for Kieslowski himself. Loosely based on the ideals of the French Republic – liberty, equality, and fraternity – the trilogy often takes on ironic interpretations, sending its characters down highly emotional pathways.

Through turbulent periods of joy and despair, the Three Colours provide a banquet of food for thought, presenting not only three great films of human character and flaw, but of moral dilemma.

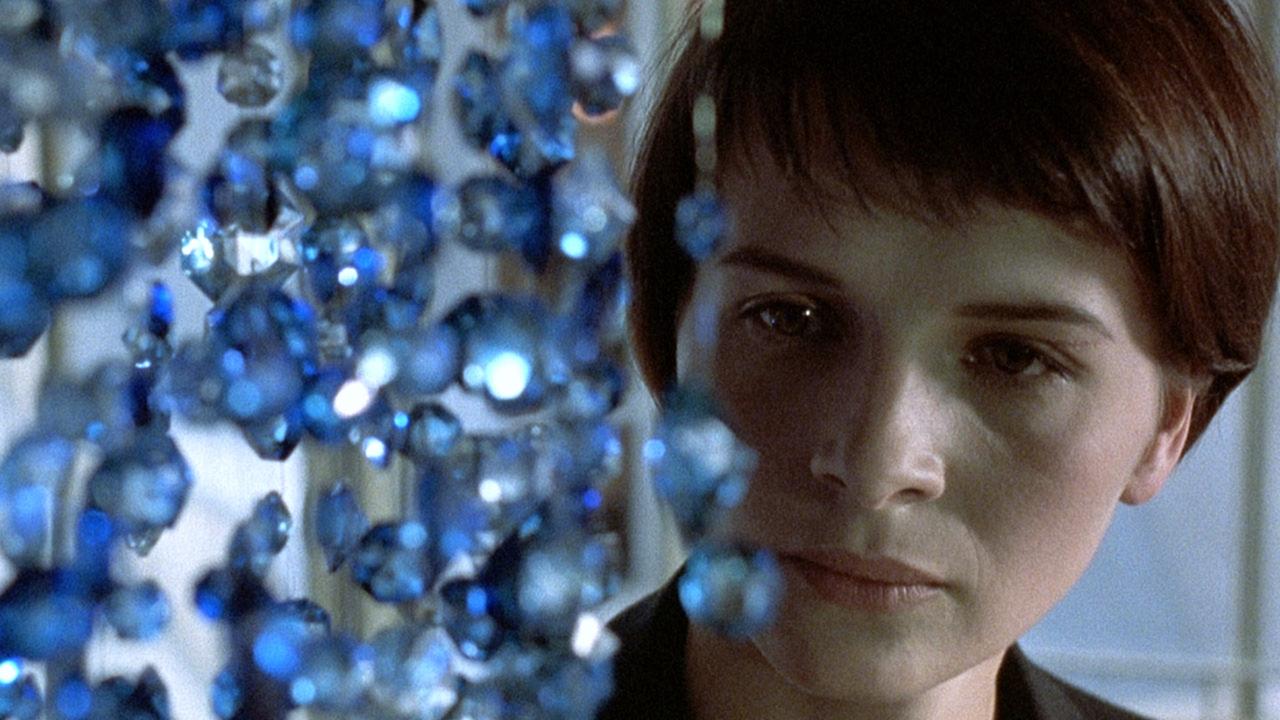

The first of the trio, Blue, tracks a woman’s attempts to distance herself from her former life after the death of her husband and daughter, but being repeatedly forced to face people from her past in often painful episodes. The film reflects on her inability to ever gain true freedom from what she wishes to escapes, making a joke out of the initial concept of liberty.

The second piece, White, is a far less disheartening tale of revenge. Beginning with a expatriate Polish man left to beg in the Paris Métro after being left by his wife, he is soon given a second chance after a fortuitous meeting gives him the opportunity to return to Poland with a mission. After a series of jobs, he schemes his way to becoming wealthy enough to take revenge on the woman who took everything from him before, balancing out the misfortune in his life.

The final film, Red, follows a part-time model and the people around her who form unlikely bonds and grow to care for each other. The three films connect together loosely, with leading characters from each appearing in the others.

4. Happiness by Todd Solondz

What stands out most about Solondz’s Happiness (1998) is the director’s fearless portrayal of contemporary themes and taboos, giving way to uncomfortable situations throughout the film. Behind the quaint suburban veneer lay heavy sexual themes; the film was deemed too controversial to screen at Sundance Film Festival.

While the topics addressed in this film are definitely issues deserving of discussion, no matter how upsetting, the provocative nature of scenes featuring paedophilia or fraud are especially difficult to watch. The depraved and almost vile nature of Solondz’s characters makes them more human than caricatured for quite scary, true-to-life viewing experience.

The film follows three upper middle-class sisters, of three different personalities, each in pursuit of happiness. The eldest, Trish, is a housewife unknowingly married to a paedophile; the middle sister, Helen, is a successful author with unfulfilling love life; while Joy, the youngest, lacks direction and is used by one of her students. Their parents are separating after 40 years of marriage, but the change in their lives fails to bring them newfound joy, instead driving them, like their daughters, to further discontent.

5. Grave of the Fireflies by Isao Takahata

Unlike most war-set films, Grave of the Fireflies (1988) shows no glimmers of pride, hope, or patriotism. For Takahata, the writer and director, the film was never about war itself, but about personal survival. Takahata has argued that the film carries no anti-war message, instead focusing on themes of isolation and depravity.

Of the choices on this list, this piece is undoubtedly the most heartbreaking and difficult to watch for all the portrayed suffering that makes its audience feel so utterly helpless, however, it is also the most important to watch. As a Studio Ghibili film, it is naturally beautifully animated and filled child-like wonder, making the misery and futility of the war all the more harrowing.

Set in the last months of World War II in the city of Kobe, Japan, Grave of the Fireflies peaks into the lives of Seita and his younger sister, Setsuko, as they struggle to survive. With their father in the Navy, they are left alone after an air raid strikes their home, killing their mother.

Taken in by their aunt, they soon leave to fend for themselves after rations run low, eventually settling in an old bomb shelter. Seita tries his best to care for Setsuko, however, their struggle becomes increasingly more difficult as Setsuko falls ill and their means to live become scarce.