Since its early years, cinema has been in a constant search for its identity. Constant definition on what and what is no cinema has shaped it history made of film movements and isolated authors who in a moment or another have wanted to push the expressive boundaries of this language.

Here is a list of 10 great films that have defined what film grammar can be, either by summarizing the mechanism of a certain epoch or by challenging them. These films display techniques that have let cinema become a mature art able to be as expressive as writing or theater, and to become what it is today.

1. The Birth of a Nation (1915)

Before directing the film that was going to be considered as the one film that put together the various attempts and experiments to develop a language that was exclusive of cinema, D. W. Griffith made several short films in which he practiced several of the techniques that were going to be praised in “The Birth of a Nation.”

Griffith made his entrance as a director in 1908, hired by the Biograph to make one or two “short films” per week, and it was in these films that Griffith would learn the way in which cinema could manipulate time and space to create emotion.

Before Griffith, there were several filmmakers who pushed the conception of what cinema could be. These pioneers started to treat film not a mere way to register reality, but as medium to transform it.

Méliès, Zecca and Porter among other were the filmmakers whose films displayed techniques that were absorbed and applied by Griffith to consolidate a film with a grammar that, while it didn’t have the fluency that would films would eventually have, it indeed had a clear dramatic and plastic structure that used the fragmenting tools of cinema to create emotions in the viewer.

This leap was needed for cinema in order to be able to endeavor in more complicated and delicate subjects, and it was with “The Birth of a Nation” that Griffith consolidated that leap.

2. Sunrise (1927)

This was the first film that F. W. Murnau did in Hollywood, and it won the Oscar for Best Picture, Unique and Artistic Production at the first Academy Awards. The film was made with the excitement of the legendary German director of who had made early German classics such as “Nosferatu” (1922) and “Faust” (1926), thus there was a big budget and a great deal of artistic freedom for Murnau.

This freedom was enhanced by the distance that Murnau took from German Expressionism and the freedom in general that an artist acquires when they make distance from the context in which his work has been developed.

This freedom, along with the maturity that Murnau had acquired after making several films, was materialized in a film that has expressionist, symbolist and realistic traits. With this picture, Murnau told the story of a man touched by temptation whose love for his wife is redeemed.

In this tale, Murnau was able to create a realistic psychological portrayal of the main character through the camera. With techniques such as travelling, transparencies, close ups and a distinction between a two and a single shot, Murnau conveyed the emotional journey and moral dilemma that the main character was experiencing. With these techniques, Murnau created a film that let cinema take another step toward the mature art that it will soon be.

3. El Compadre Mendoza (1933)

Legendary Mexican director Fernando Fuentes crafted in 1933 a film whose techniques would be both a resume of the latest techniques developed in American and European cinema, and an advancement of techniques that would be used in films many years after.

Coherently with the advancement of world cinema as a medium able to express more complicated subjects and processes and with the technological advancement of sound, Fuentes created a film that was deeply expressive in many ways. It displayed the story of a Mexican yeoman who, due to his sympathy for all of the revolutionary sides and the government, end ups in a moral dilemma that involves friendship, honor and ambition.

Fuentes structured the film in a very interesting way, both dramatically and formally. It has subplots in which a deaf servant spies on the yeoman and a government captain, which Fuentes would structure much like the scene of “2001: A Space Odyssey” in which Hal spies on the astronauts. It also has moments of unspoken affection and a mutual understatement in which the silence becomes expressive by the mise-en-scene and the fragmentation that Fuentes makes through the camera.

4. La Grande Illusion (1937)

One of the greatest French masters of cinema is Jean Renoir, revered by les enfants terribles of the André Bazin’s circle who thought of him as one of the greatest filmmakers who had ever lived.

Perhaps his first masterpiece is “La Grande Illusion,” a film that was the result of the French poetic realism of the 1930s, which used technological advancements to create a cinema in which the subject was the city and its outcasts. This was a film that was made with extreme care and precision, characteristic of films of Renoir, but also with a great sensibility and an interest in conveying a side of the human condition.

Regarding this film, Orson Welles said that he would save it if he could only save one film in the world. This affirmation by Welles can be understood when one thinks of the main techniques that were developed both in this film and in French poetic realism, which strongly influenced the films that Welles would eventually make.

Dialogue, atmospheres and mise-en-scene were the main expressive tools that Renoir used to craft this film. In the portrayal of the war that Renoir made in “La Grande Illusion,” the frames are composed in such a way that they acquire powerful expressive values that have never been seen in film form.

5. Citizen Kane (1941)

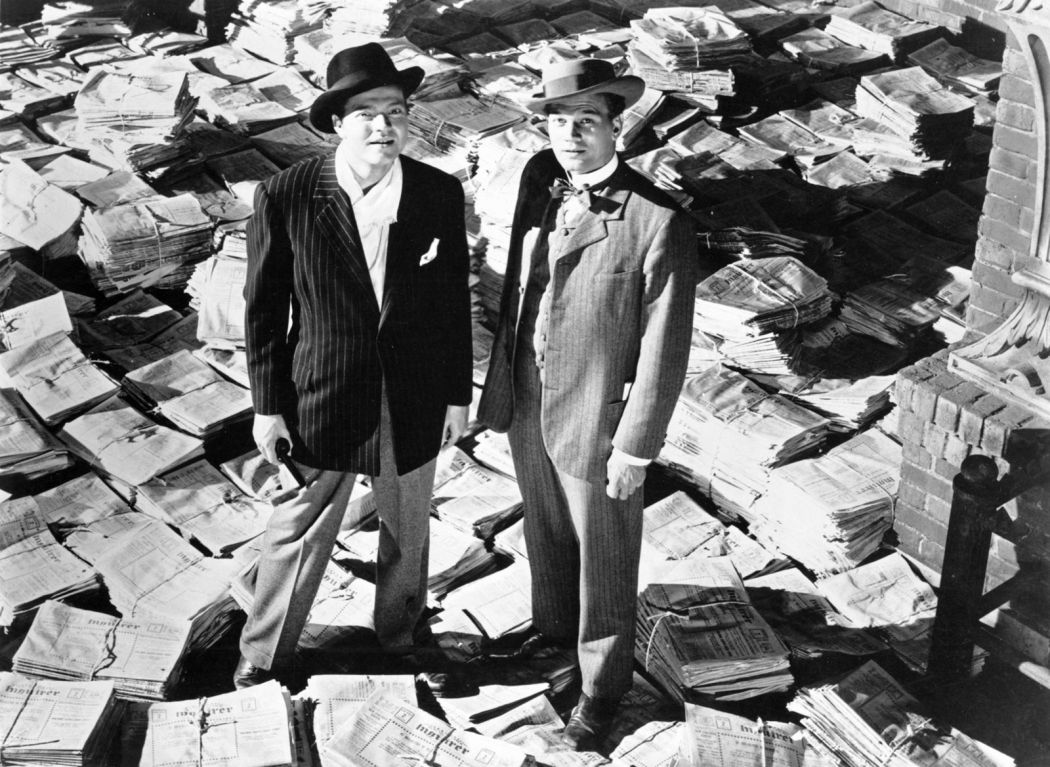

A deal was made with a man who had managed to fool the United States through a radio adaptation of “The War of the Worlds.” This deal allowed the young Orson Welles to start a film in which he would have almost complete artistic freedom, and even though it was the first film of his career, it would become of the most influential films in history.

Welles was educated not in the film industry but in theater, thus he approached cinema with the ambitions of an artist and a great deal of either ignorance or courage (probably both), which led him to create a film that redefined film grammar and the conception of what a film could be.

Welles crafted “Citizen Kane” in collaboration with a man who, unlike him, had a lot of experience in the film industry: cinematographer Gregg Toland. This veteran of cinema wanted to work with someone like Welles, who was able to push him beyond what other directors accustomed to the common idea of cinema could.

It was this collaboration that allowed both of them to take the deep focus techniques to their highest potential. They created a psychological portrait of Charles Foster Kane in which the deep focus of the camera allowed them to compose the frames in such a way that they become extremely more dynamic, and the mise-en-scene became much more expressive due to the position of the camera.