6. House (1977) Dir. Nobuhiko Obayashi

Nobuhiko Obayashi’s “House” has over the years remained one of the weirdest horror films ever made. When this film was released, Japanese critics didn’t give positive feedback, but audiences loved it and it became a box office success in Japan. Unlike Japanese critics in 1977, American critics praised this film when it was re-released in the United States in 2009.

In order to make this film, Obayashi decided to consult his teenage daughter for story ideas. Instead of using all her ideas, what he did was to pick the ones he loved so he could work on her childhood fears. The result was this psychedelic trip in which childlike fears are shown to the viewer as if a child would have made the special effects. Obayashi wasn’t really satisfied with some special effects, but ironically, they are what most people love about this film because they add humor and charm.

In “House,” a young girl named Gorgeous plans her summer vacation with her father. He surprises her by announcing she has a stepmother. In an attempt to avoid being with the unwelcome newcomer, Gorgeous decides to pay a visit to her aunt, who lives in a remote mansion. In this estate, Gorgeous undergoes the paranormal elements that occur almost as soon as she gets to the mansion: a severed head takes off and flies, ending up biting Gorgeous’ bottom, and a cat and its portrait seem to be cursed.

If you’re prepared for this disturbing and surrealistic Japanese movie, this might become one of your favorites, since it has been considered to be one of the essential Japanese films.

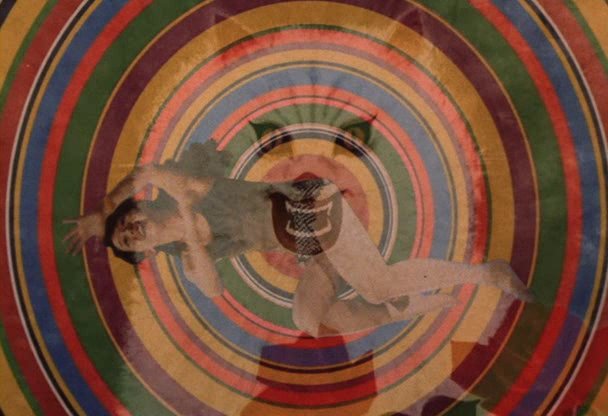

7. Mysteries of the Organism (1971) Dušan Makavejev

Be aware that this might be the weirdest from this list. The film delves into communist politics and sexuality, showing the viewer Wilhelm Reich’s ideas about sexuality and character. The main idea of the film is so different that it’s difficult not to feel curious about watching it, and if you think the film is not weird enough, the narrative’s structure mixes fictional and documentary scenes, which makes it easy to get lost.

The film was banned in Yugoslavia for 16 years due to its high sexual content and satirical message. In fact, the director was accused of derision against the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Makavejev had to flee his own country until the end of the regime in 1992 if he wanted to avoid going to prison.

What the viewer finds in this film are several intercuts documentary footage and clips, mainly from the hagiographical film about “Stalin the Vow” (1946), and the story of a Yugoslav woman who entices a Soviet celebrity ice skater into sexual activity. Critics don’t consider this to be a sex film since Marx and Freud, two great influential thinkers who had a great impact on Reich, believed that sexual freedom was a true expression of communism.

Some think that this film is just a metaphor of Russia’s relationship with Yugoslavia in the 1970s. This metaphorical film shows how the woman fails to comply her proletarian conviction in order to seduce the Soviet ice skater, who would symbolize class oppression and corruption.

In order to completely enjoy this film, the viewer should be interested in experimental films. It’s not the kind of film you would watch a Saturday night with your friends eating pizza. “Mysteries of the Organism” is a political and moral satire in which the viewer sees Yugoslavia trying to choose between the ideas in the East or the West.

8. The Color of the Pomegranates (1969) Dir. Sergei Parajanov

Parajanov’s poetic and mystical film has appeared in some scholarly polls of the greatest film ever made, and once you’ve watched the film, you will no doubt that this is one of the greatest films that will make you have a different and unforgettable cinematic experience.

Although this film is hard to understand, “The Color of the Pomegranates” is an absorbing film that plays with the hermetic visual language. In fact, the hieratic figures, the vivid colors, and the religious elements of the film may remind the viewer of Hieronymus Bosch’s paintings in which there’s no need for words, as the images speak for themselves.

The film is based on the 18th century Armenian poet, musician, and ashugh Sayat Nova, who lived most of his life in a religious society but wrote mostly secular and romantic poems. The film is divided into different chapters which shows Nova’s relevant events in his life: Childhood, Youth, Prince’s Court, The Monastery, The Dream, Old Age, The Angel of Death, and Death. The lack of dialogue, the folkloric music, and the static camera gives the viewer the feeling of being in a dream. The Armenian atmosphere of the film is a bewildering experience for Western viewers, who are bound to get trapped as soon as they start watching it.

If you love Tarkovsky’s films, Parajanov’s “The Color of the Pomegranates” is a good choice. In fact, Parajanov admitted that Tarkovsky “was [his] teacher and mentor. He was the first in Ivan’s Childhood to use images of dreams and memories to present allegory and metaphor. Tarkovsky helped people decipher the poetic metaphor.”

This film is a poetic masterpiece composed of beautiful tableaux that would make you enjoy watching dreamlike things such as weeping books, bleeding fruits, floating instruments, actors staring at the camera, and much more.

9. The Cut Ups (1966) Dir. Anthony Balch

The cut-up technique, or découpé, is a literary technique that was introduced by the Dadaist Tristan Tzara in the 1920s. In the 1950s, the painter Brion Gysin rediscovered the cut-up technique. He wanted the beat writer William Burroughs to know about this technique, which was believed by both of them that it would show the true meaning of a given text.

In August of 1962, Burroughs met through Gysin the British director Anthony Balch. Balch had made several low-budget horror films, but he wanted to meet Burroughs in order to experiment with filming some of his cut-up texts. According to Burroughs, the cut-up texts were produced to “make explicit a psychosensory process.”

This collaboration film was part of a project called Guerrilla Condition. What the viewer finds in this short film are the voices of Burroughs and Gysin saying permutations of the phrases: “Yes / Hello / Look at this picture / Does it seem to be persisting? / Good / Thank you.” This repetitive irregular pattern of sentences are uttered randomly, and it doesn’t seem to have any apparent meaning.

The asynchronous voice-overs were based on a Scientology auditing test. The film forces the viewer to watch a series of flashing images and listen to Burroughs’ and Gysin’s voices, which sound simultaneously and sometimes overlap. The aim of this film was to remove the coherent, linear narrative structure.

When this film opened in 1967 at Oxford Street’s Cinephone in London, where it was played for two weeks, the audience came out from the cinema enormously disappointed and demanding refunds. Balch confessed in the magazine Sight and Sound that he really enjoyed watching the audience demanding refunds because it showed that they were really “getting to them.”

He also claimed that “half the audience would love it and half would hate it” because that was what they intended. If you love avant-garde films such as “Le Retour a la Raison” (1923), “Entr’acte” (1924) or “Ballet Mécanique” (1926), “The Cut Ups” is a great movie that shouldn’t be overlooked and forgotten.

10. Kwaidan (1964) Dir. Masaki Kobayashi

The literal meaning of the title, (怪談) ghost stories, advises the viewer of what they’re going to find in Kobayashi’s film. Kwaidan is based on Lafcadio Hearn’s “Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things,” which is a collection of Japanese ghost stories and a brief study of Japanese insects. The film is divided into four different parts that don’t have any connection between them. The chapters are: “The Black Hair,” “The Snow Woman,” “Hoichi: The Earless” and “In a Cup of Tea.”

In the first story, an impoverished samurai divorces his wife and leaves Kyoto in order to get married to a selfish and rich woman. He realizes that he’s unhappy, and that he doesn’t really love his new wife; he constantly longs for his first wife. One night, after having an argument with his second wife, the samurai decides to leave her and go back to his old life. However, when he returns, he finds an unexpected surprise.

It’s remarkable how the sound and lightning are the key functions in each scene. In every story, the disturbing sounds startle the viewer, and the lightning suddenly changes to introduce us into a phantasmagorical atmosphere.

The second story shows the moment in which a woodcutter, Minokichi, and his mentor, Mosaku, take refuge in a hut during a snowstorm. The mentor perishes, he’s killed by Yuki-onna (The Snow Woman), and the young man is spared because of his youth and beauty, under the condition that he shouldn’t tell anyone about what happened or she’ll kill him. Later on, he meets a woman who travels to a distant city, but she’ll never arrive to that city because she gets married to Minokichi. What Monkichi doesn’t know is that his wife hides a secret.

In “Hoichi: The Earless,” what the viewer finds is the film adaptation of the story of this Japanese mythological character. Hoichi, a blind musician or biwa hoshi, sings the famous Tale of the Heike. When he’s called in to sing for a royal family, his friends and the priests are concerned about the ghosts that could be brought by the singing, so they decide to protect him writing on his body The Heart Sutra.

Last but not least, “In a Cup of Tea” the viewer finds the story of a writer who writes about a samurai who constantly sees the face of a man in a cup of tea.