6. Pierrot le Fou

The other French New Wave auteur on this list is Jean-Luc Godard, whose films often have a visual flair despite their unorthodox natures. Pierrot le Fou is characteristically chaotic, with oddballs that escape the conventionalities of life to go to the Mediterranean Sea.

Raoul Coutard makes the foreground subjects punch with vibrant colours, so the backdrops of the deeply blue sea exist peacefully behind the shenanigans taking place. You can just smell the salty air and feel the gentle breeze that coasts through the scenes here, even with the jarring edits and cheeky narrative. Pierrot le Fou is all about a departure from reality; this might be the most peaceful aura any Godard film has ever projected.

7. Summer with Monika

Ingmar Bergman’s proposition that existentialism can only go so far is Summer with Monika (one of his first real successes). Gunnar Fischer perfectly makes Sweden look like a dungeon before the to-be-permanent excursion to the archipelago. Once we get to the islands of Stockholm, the air is open and the water is at peace.

We begin to learn that even an open world does not help closed off people, and the seaside begins to torment us (despite never changing). Bergman loves to work with reflections (via windows, mirrors and the like), but the self-meditation that comes from the glass-like water is an otherworldly achievement.

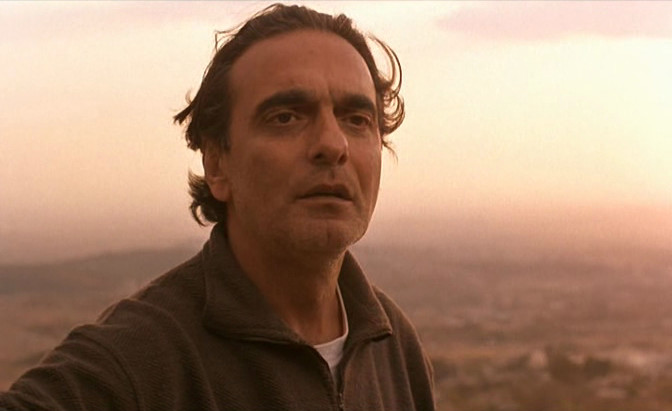

8. Taste of Cherry

There’s no doubt that Abbas Kiarostami is an integral figure in art house and Iranian cinema. Taste of Cherry is one of his finest examples for his prominence. Even with a dismal subject, the world that Mr. Badii endures looks richly colourful as he drives around.

The appropriately named film lingers through the visual content, as nothing is deeply red: it’s simply tinted just right. Homayvun Payvar balances the right amount of natural influence and artistic decision-making here, because the scenery is sublimely uniform. With a tricky subject matter, the landscape that floods the screen will invite you to revisit what the world can offer you naturally.

9. Ugetsu

The final film here is Kenji Mizoguchi’s love letter to the spiritual side of Japan. With a poetic tale that dives into the arms of a ghostly figure, Ugetsu is boldly placid with its setting. Kazuo Miyagawa captures the mist that rises off of Lake Biwa perfectly, reminding us that spirits can exist in other, natural ways on Earth (and not just via our own depictions of the dead).

Trees are bare and reach for the sky as if they are held prisoner, yet they show no malice. Grass is tall but it does not stand boldly. Much about Ugetsu is mystifyingly stern, yet it is all soothing to witness; it is simply hypnotic.

10. Days of Heaven

Yes, a Terrence Malick film is here. It is difficult to pick just one film of his that showcases the wonderful ways of the world the best. Days of Heaven narrowly wins because it contains so many facets. It is the starting point for settlers and workers. It is the vast spaces between us. It is golden and sepia to place us in a different time; as if we jumped into an old photograph.

The works of Néstor Almendros and Haskell Wexler behind the camera enrich the shimmer found within the Texas Panhandle during World War I. When the plague of locusts takes place, all is but a deep, bronze glaze. Days of Heaven truly does feel angelic visually.

Author Bio: Andreas Babiolakis has a Bachelor’s degree in Cinema Studies, and is currently undergoing his Master’s in Film Preservation. He is stationed in Toronto, where he devotes every year to saving money to celebrate his favourite holiday: TIFF. Catch him @andreasbabs.