Films are an escape for many. You visit a theatre to be ripped away from reality. You prepare your television or computer to revisit a unique place that wowed you on the first watch. The entirety of many films is a very specific experience that can be described plainly as “cinematic.” Think about it: that epic ending to your favourite war film is glamorized by swelling instruments, artistic shots, and other non-worldly elements that enhance the predicament. This can be applied to the entirety of many films.

However, some films revel in their realism to create what is, oddly enough, a counter-effect to what you usually get from a film. In “Come and See,” the sounds and visuals don’t heighten the moment or pretty up the scenarios; you are attacked by the real thing, and the entire trip is uncomfortable.

See, using common film tropes isn’t just for making a film more captivating, but it usually makes a film easier to digest in return (while this is not always the case – see idiosyncratic films like “Possession” – it at least makes the film clearly a form of entertainment, and the divide between reality and fiction is set in stone again).

Some films (even ones that may feel cinematic for the most part) end in ways that are not towering forces or structured climaxes. Some films end realistically, which, once again, usually results in a very jarring conclusion to a cinematic journey. At the end of these films, you will be leaving the theatre (or sitting back in your chair) with bewilderment. Sometimes this translates to either astonishment or even befuddlement (to the point of, perhaps, not liking the ending).

Nonetheless, these are 10 films that conclude in a way that will shock you to your core, either through narrative structure or through the lack of cinematic conventionality. These are 10 great movies with shockingly realistic endings.

Of course, it goes without saying that all of these entries will include spoilers. Read with extreme caution.

1. All the King’s Men

We are not looking at the subpar 2006 film by Steven Zaillian. No, we’re instead observing one of the most underlooked Academy Award Best Picture winners ever. The film is directed by Robert Rossen and starring Broderick Crawford as the politician Willie Stark, whose rises-and-falls and changes-of-heart continue to ring in any tainted character in films ever since. The film starts off promisingly, as you witness an everyday man’s will to change society for the greater good. As the film progresses, however, Stark gets power hungry. Corruption becomes the go-to tactic for many of his decisions, and society starts to notice.

The resolution of the film could bring Stark back to his senses, and cause him to fight for the greater good. Instead, you witness a disturbing ending (especially for 1949, when many mainstream films were sanitary in comparison) where Stark gets brutally assassinated.

That’s it. Glass shatters, and bodies fall. Due to the production code, many films around this time were made to end on a positive note. Not Rossen’s “All the King’s Men,” of which let the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel it was adapted from continue to tell its tale of comeuppance.

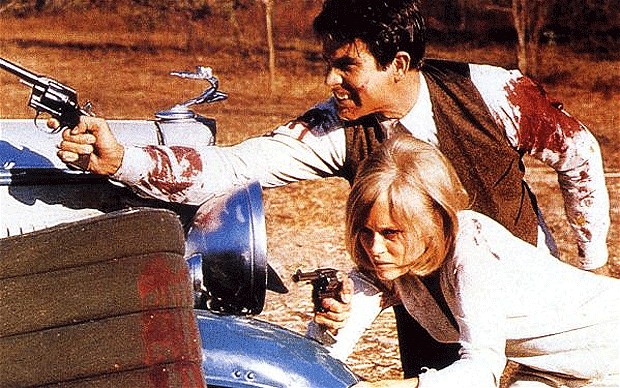

2. Bonnie and Clyde

Arthur Penn’s B-movie-turned-Oscar-contender, stuffed with innuendos and disturbing imagery (it was reportedly the first film in history to feature both a gun’s blast and a victim’s burst wound within the same shot), attracted audiences from all over the nation. One of the many moments that made “Bonnie and Clyde” a counterculture classic is the infamous conclusion.

The titular Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow are in a car when they pull over to help a familiar face, Ivan Moss (the father of their getaway driver). Without weapons at the ready (as Bonnie and Clyde trusted Ivan), Clyde leaves the driver’s seat (and Bonnie in the car) to tend to Ivan’s flat tire. Suddenly, birds begin to fly away due to some sort of disturbance.

Clyde and Bonnie realize when it is too late: the police are hiding in the bushes. The two get one last final gaze into each other’s eyes, and they are then riddled with a gratuitous amount of bullets. After both lovebirds have been shot beyond recognition (Bonnie limp in the car, and Clyde lifelessly rolling down a hill), the police inspect the bodies. Once their deaths are confirmed, the film ends, because that truly was the end of Bonnie and Clyde; you can’t dance around it.

3. Call Me By Your Name

The most recent example here is Luca Guadagnino’s queer romance “Call Me By Your Name.” Most of the film features the slowly developing love between Elio (the son of an esteemed professor) and Oliver (the American student who helps Elio’s father).

At first, there is a slight tension between the determined Elio and the confident Oliver. As the film progresses, they see eye to eye, and they discover their feelings well into Oliver’s stay (to the point that so many days were wasted beforehand). Oliver eventually departs back to America, and Elio’s father teaches Elio to not push aside his sadness, but to instead appreciate his love as both a blessing and a tragedy (through a spectacular monologue by Michael Stuhlbarg).

The film is about to come to close, and it feels pleasantly bittersweet. Yet, the film fast forwards to many months later, and Elio finally hears back from Oliver; he discovers it is just a warning that Oliver is actually engaged to another from back home. The final shot of Elio’s face in front of the fireplace is hauntingly sad. He is torn between experiencing the sadness, as his father told him to, and trying to dismiss the moment because it is too painful. Of course, that’s when the credits roll, because not every happy story ends as cheerfully as they thrive.

4. Chinatown

Roman Polanski’s neo-noir masterpiece “Chinatown” can be taught as a course in university. There are so many layers to what is going on with this film, especially when it comes to the countless ways it shatters both film noir and film as a whole. While the entire film feels pretty gritty and authentic, you still feel as though you have to stick by Jake Gittes’ side until the very end. What started off as an investigation behind a supposed affair turns into a discovery of an entirety of hell within California that feels unstoppable.

Can the hero of the hour save California’s political and societal structure? Is it up to this one man with all of the answers? Seeing as you’re reading this list, you can gather that the situation is, in fact, far too big for him. Gittes’ client Evelyn Mulwray (revealed to have been raped by her own father, thus being a sister to her own daughter) is finally telling him the truth, since he may be the only answer to stopping the amount of corruption her father, Noah, has sparked (within the water department, flow of finances, and the police force).

Instead, Evelyn is shot in the back of the head (with a bullet wound through one of her eyes), and her head drops onto the steering wheel (thus setting off a long, disturbing blast of the car horn). Her fleeing daughter is stolen away by Noah under the noses of all, and Gittes is told to forget it, as “it’s Chinatown” – the place Gittes once fled due to similar conflicts. That’s the film’s way of saying this is the end, because life is sure ugly when it wants to be.

5. Dog Day Afternoon

Sidney Lumet’s “Dog Day Afternoon” is known for its many forms of realism. Firstly, there is a lack of non-diegetic music (scores or songs that do not come from within the confinements of a film’s scene [a record player or a person singing in the scene], but instead as an other-worldly track placed on top of the scene) present.

Secondly, the film, while not paced in real time, is set to feel as though you are witnessing all of the events of a hostage situation gone awry. Sonny is ruthless in trying to keep order, out of fear of failure and determination to get his group out alive. After plenty of negotiations and threats, Sonny finally agrees to be personally driven to an airport so he and his main partner-in-crime Sal can flee in peace. Sal, clad with a gun, is Sonny’s cover in case anything were to happen.

At the very last second, the law wins, as Sal is fatally shot and Sonny is immediately arrested once his protection was removed. “Dog Day Afternoon” was based on a similar robbery/hostage scenario that happened in Brooklyn in 1972, yet that terrifying conclusion of the near-capture of the American Dream will feel as though you saw the actual event.