Originally used in theater, mise-en-scene is one of the most powerful concepts/tolls of filmmaking. It involves the arrangement of what appears in the frame, and the relation of it with the camera. The French term is used in every film from neorealism to contemporary filmmaking that draws away clearly from realism.

David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson write about mise-en-scene in “Film Art: An Introduction,” and explain that the term helps to signify “the director’s control over what appears in the film frame” and thus “includes those aspects of film that overlap with the art of the theater: setting, lighting, costume, and the behavior of the figures.” The significance of all of these elements is influenced by the angle, location and movement of the camera, and thus it becomes a most significant part of the technique.

One of the first films to display a “complete” mise-en-scene is “Citizen Kane.” Thinking about the collaboration of a theater man (Orson Welles) and a veteran of film (Gregg Toland), one can imagine why this film expanded film’s technique as it has never been seen before. Some of the primordial techniques that Toland and Welles used in their film are not strictly part of the mise-en-scene, but they indeed help them use it in the way they wanted: soft focus and greater depth of field.

From “Citizen Kane” to years to come, filmmakers would use soft focus and depth of field to capture more complex shots with memorable mise-en-scene. “Citizen Kane,” being the partway of cinema that it is, deserves a mention outside a list as the movie that condensed and was ahead of a technique that was going to be used by all filmmakers for years to come.

10. Songs from the Second Floor (2000) – Roy Andersson

Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson is one of the most challenging and groundbreaking directors still working. His films draw considerably away from Classic Narrative Mode, thus there is not a single conflict that unifies the actions or the characters. In his films, we see fragments of characters living in a strange and fatigued world that kind of reminds us of the exhausted characters of “La Notte” by Antonioni. But being groundbreaking does not mean that Anderson does not use the same tools of other filmmakers – it just means that he uses them in different ways.

In “Songs from the Second Floor,” we see dramatically disconnected fragments of characters struggling with a world that is very different from ours, yet very familiar. Andersson, against the classical techniques of fragmentation and juxtapositions, films these fragments in single full shots where the characters sometimes move and sometimes remain static in their positions.

There are constant secondary actions going on in the background of the shots and the makeup for everyone are very artificial, displaying the characters as almost dead. Andersson subverts filmmaking to create his own language, just as the very great filmmakers have done.

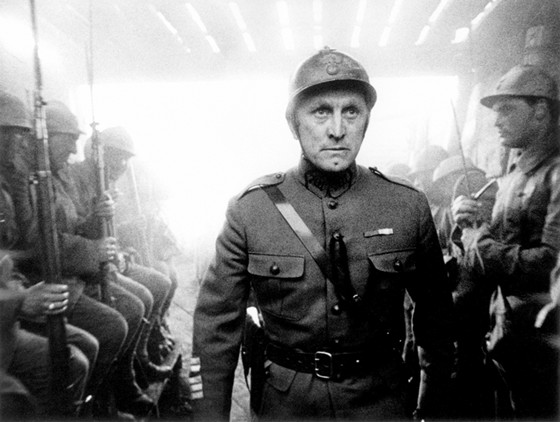

9. Paths of Glory (1957) – Stanley Kubrick

This is one of Kubrick’s earlier films, perhaps the first masterpiece of his career. It is a simple film in contrast to the high production values of his other films such as “Barry Lyndon” or a “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Yet this film is extremely powerful and does not lack the philosophical and complex thinking of other Kubrick films. In this film we see Coronel Dax, played by Kirk Douglas (who in that time was a bigger name than Kubrick), struggling to defend three of his soldiers from a punishment which they do not deserve.

The film displays the power relationships of the army as the high-tempered Colonel Dax faces the high commanders with the truth that they are as responsible as the soldiers for the failure. Colonel Dax defends the soldiers in courts full of people and in big rooms where there is only him and a high commander. In these confrontations, Kubrick and the actors structure their movements in a way that expresses how Dax is either winning, losing or struggling the argument for the leitmotiv of the film: justice for the soldier.

8. Ulysses’ Gaze (1995) – Theo Angelopoulos

Greek filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos is another one who mastered the long take technique to the point where he can make extremely compelling scenes without even moving the camera (one of this moments is mentioned in our “Most Moving Scenes in Film History” list). Angelopoulos makes extremely complex and deep frames in which every aspect of the space and movement becomes significant. He makes frames within frames and structures movements not only in a significant way, but also in a rhythmic one.

A, a successful filmmaker (Harvey Keitel), returns to his homeland in the postwar Balkans to travel all over them in search of three lost reals. In his journey, he revisits physical places and moments lost in time. With uncut shots where A moves through houses and towns, the line between reality and dream is faded. The journey leads him to Sarajevo where he encounters S (Erland Josephson) and his wife (Maia Morgenstern). Sarajevo is covered by fog that Angelopoulos uses to make the characters appear and disappear as they move, implying maybe this fragile line between dreams and reality, and between past and present.

7. Tokyo Story (1953) – Yasujirō Ozu

This film displays the story of a family in a silent crisis. This crisis is characterized by old parents that are now grandparents, the struggle to find a place in the lives of their offspring who now are parents, and struggle to find the time and patience for their parents. This film displays Ozu’s long time collaborators Setsuko Hara, Chishū Ryu and Haruko Sugimura. It is the story of every family told in the unique and tender style of Yasujirō Ozu.

The style of this Japanese filmmaker is often described as a depuration of film language in favor of simplicity. Ozu rarely moves his camera and his framings repeat themselves constantly, not only in this film but in all of his films. In “Tokyo Story,” we see how Ozu uses frames within frames and the movements of the actors to evoke their emotional state. He takes time to show people just being together, without any unnecessary cuts of fragmentation, making us focus only on the mise-en-scene. This mise-en-scene is extremely simple and effective; it is the proof of a filmmaking mastery rarely achieved by an artist.

6. Playtime (1967) – Jacques Tati

French filmmaker Jacques Tati risked everything for “Playtime” to be made. It needed to be a commercial success in order to recover the massive investment; it was not, but it was indeed an artistic success. Tati made a masterpiece that embodies his unique style and personality; it displays Tati’s character Monsieur Hulot’s (played by himself, like Chaplin’s or Keaton’s characters) struggle against the inclement modern world.

Without any close-ups in the entire movie, Tati uses constant wide shots to make extremely funny and ironic gags. Instead of fragmenting space and actions, the technique of “Playtime” is to show simultaneity. For example, the film shows two rooms next to each other, where two people who have been looking for each other are separated only by a wall without knowing they are so close; this scene is done only in one shot, which lasts several minutes stretching in duration and irony. The film is made strictly of these impeccable filmed and staged scenes by the genius of Tati and his crew.