Film history is full of films which stick in the memory, good or bad, but is also (perhaps even more so) full of films which seem to be remembered and live on, if that is the right term, as what may be referred to as “text book classics”. This term simply means that while these films are often mentioned in books concerning film art or history, they don’t get seen or, especially, talked about by viewers/students all that often.

Why would this happen to work good enough to be cited in scholarly works or historical surveys? A number of reasons could apply. It’s not unheard of for films to be taken out of wide circulation (or out of circulation at all) for legal reasons or because the owners of the films don’t consider them and their like to have enough commercial value to keep in rotation.

Perhaps, also, a change of styles might make the films and their achievements look decidedly old-fashioned and run of the mill (in large part, in many cases, due to the fact that said films had their innovations were so incorporated into the filmmaking fabric that the originals now look like trite retreads).

Also, some films were made by talents who had dazzling moments but then had careers which failed to live up to those moments or which didn’t stand the test of time well. Sadly, with so very many films throughout the medium’s history, some just got left in the dust after a while.

The following films were either popular or well regarded or both in their own times or at some time thereafter but now seem to be a bit lost on modern audiences and viewers. They all had influence in the film world in one way or another and there well may be a book or two (or three or four) which mentions them but current viewers and/or audiences rarely seem to bring them up. Hopefully, this list may shed a bit of light on them.

1. October (Ten Days That Shook the World, 1927)

In his excellent scholarly history of cinema, A History of Narrative Film, author David Cook makes a great case for each of the renowned film makers of the early days of the Soviet Union (from the late 19-teens through the 1930s) having been allowed only one clear shot at creating uncompromised works of film art. There was one slight exception and many thought, and think, of him as the greatest of them all: Sergei Eisenstein.

The master of cinematic montage, however, was actually only a bit luckier than his compatriots. In 1925 he produced both his debut feature, Strike, and his eternal masterpiece, The Battleship Potemkin, both largely without government interference. This is understandable since both pretty much towed the party line (which Eisentstein believed in to a large extent).

However, the trade off for that golden year was to be a remaining lifetime (both creative and physical, since the film maker didn’t live to be very old) filled with compromised and unfulfilled projects. Most of those, such as the 1938 sound film Alexander Nevsky, and the two Ivan the Terrible films (1944 and, way posthumously, 1958), and even the uncompleted Que Via Mexico! (shown in an incomplete edit in 1978), have attracted their fair share of attention down through the ages. However, one film which seems to be in danger of being left behind is the film which came just after Eisenstein’s double header: October.

Just as Battleship Potemkin was created as part of a massive celebration of the aborted Russian 1905 revolution, so October (somewhat based on US reporter John Reed’s famous account Ten Days That Shook the Earth) was created to celebrate the famed October revolution of 1918 which swept the Bolsheviks to power.

As with his early films, though the film maker was somewhat concerned with the messages which extolled the principals of the revolution, he was even more concerned with his penchant for choosing striking and telling images and with his dynamic theories of editing (montage, which was influential way outside his homeland, though it was supposedly cut off from the rest of the world culturally at that time).

To this end, Eisenstein succeeded in creating a work of stunning images and brilliantly edited set pieces (such as the siege on the bridge) but the main plotline and various episodes ended up truncated. Why? Sadly, the real-life political world whose origins the films was celebrating intruded. The film sought to glorify the heroes of the revolution and one of those, and a prominent figure in October, was Leon Trotsky.

Though his swift downfall was surely no surprise to those in power circles, it caught most everyone else off guard, Eisenstein being no exception. The censors demanded all traces of Trotsky be removed from the film (and everywhere else, effectively erasing him as a person long, long before the assassin they sent to his hiding place in Mexico ended the man himself). This automatically caused a full quarter of the film to be removed and several sequences to be reshaped.

In earlier times, critics and historians were able to accept the good in the film without dwelling on the misfortunes it endured. However, in later times, when only a director’s cut is truly acceptable, October began to be considered “damaged goods”. While the full vision of any film maker is preferred, is it wise to throw the baby out with the bathwater in such cases as this? If one chooses to do so, then much fine work, even in an imperfect film, will be lost.

2. The Crowd (1928)

King Vidor was one of the real greats of the first half century of Hollywood film making and created one of the best films and biggest hits on the silent screen era in 1925’s moving war film The Big Parade. Sadly, after a few more hits, he made what has to be considered his masterpiece, only to have the studio brass (at M.G.M., his home base) dislike his work and the public (largely due to studio underhandedness) give that work the cold shoulder. That film was The Crowd, one of the most personal and sincere works ever to be made in Tinseltown (and it itself has no tinsel).

The Crowd follows the life of a nice, but unexceptional young man (unknown James Murray, who would come to a tragic end due to his brush with fame, among other things) with a loving but unexceptional wife (Eleanor Bordman, then actually Vidor’s wife) both trying to make their way in the anonymous crush of a big city (New York City, to be exact) and finding a few happy days and a lot of really bad ones along the way, finally accepting that they are just part of “the crowd”. It was such an honest film (and Vidor filled it with every truthful touch which would fit into the picture) but an upper it surely wasn’t.

This last part was the big point of the film: life doesn’t always (or often) play fair, hard work doesn’t always get the worker anywhere, bad things can happen to decent people, and how we make out in life, either with a lot or a little, depends on how life is met and accepted. Studio chief Louis B. Mayer, who had something of a fairy-tale like rise to the top, frequently extolled the greatness of the US (his adopted homeland) and how anyone could be anything they wished to be with enough hard work.

Time, let alone realism in any era, has shown how much more knowing and sophisticated was Vidor’s vision, which was much more on the nose, but it didn’t help. At the time of the film’s release the capper was that it actually won one of the two production awards, namely “Most Artistic Production”, given out in the Motion Picture Academy’s first year in lieu of a Best Picture.

Sadly, Mayer argued the then small body governing the Academy into awarding, not his own studio’s film, but the Fox Film release of the great F.W. Murnau’s different but equally great masterpiece Sunrise (a film that does still get talked about). Vidor was also nominated and also lost and there went the film’s chance to get into the books in that manner.

Shortly afterward, the sound era started in ernest and most silent films were thrown into vaults (or worse) until a much later time when there was renewed interest in them. The Crowd is, thus, a real text-book classic but it deserves better. Though Vidor himself had to compromise and make his fair share of false, sentimental, and/or sensationalistic films, this film still serves as an inspiration to those who have come after and wish to use film to tell important truths about human beings and how they live.

3. A Nous La Liberte (1931)

Just as people of a certain age in history would have found it difficult to conceive of another time when such qualities as charm, lightness of touch, sweet natured humor and mischievous invention would be looked at in a skewed way, so its hard for many of the modern era to understand a world wherein those very qualities were revered.

This very fact may well explain why the wonderful films of France’s Rene Clair, seen at their best in the late silent and early talkie eras, are now consigned largely to film history tomes. The odd thing is the Clair’s period of greatness, coming at one of the worst economic times in world history when the continent of Europe was still recovering from what was then the biggest war in history, was still able to accommodate so many warm, funny, charming and very human qualities.

Though he had hit with the lovely silent The Italian Straw Hat (1928) and the early sound film Under the Roofs of Paris (1930), and would also hit in 1931 with the souffle light charmer Le Million, A Nous La Liberte would prove for many years (always?) to be his calling card film.

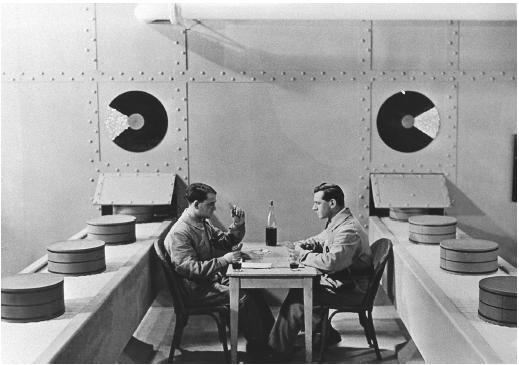

The story finds two hapless ner-do-wells incarcerated in what looks, in all honesty, to be one entertaining prison. One escapes early on and thus they end up parting ways, one to freedom and other back to prison. After the imprisoned one is finally released and enjoying the natural life, he discovers that his old co-hort is now the wealthy owner of a phonograph factory (and even that carries an old-fashioned charm to it).

The factory owner, now not nearly so friendly, allows his old cell-mate to take a job on the assembly line in order to keep him quiet but the former jailbird soon finds out that he’s just exchanged one prison for another. After much lovely humor and a number of nice songs, a non-realistically happy ending in achieved.

This film might just be the polar opposite of The Crowd but this only shows that the world of the cinema is so multi-faceted that it can hold both types of films and have them both turn out to be treasures in their own different ways. The main characters in The Crowd end the film by setting their many troubles aside and going to a movie theater to laugh for a little while.

The film that they are seeing might well be one much like A Nous La Liberte. It takes a gift to make fine entertainment of any kind but one of the hardest types to do well is escapist works with the needed dose of reality turned on its head in order to make it funny. Clair had an absolute genius for that sort of thing.

This film throws in penal problems, labor difficulties, social prejudice, the feeling that modern man has been reduced to a cypher, and other such things and, yet, its still so joyous. And now so dated. Clair has largely been considered out of fashion since the time of World War II (he fled France and returned after the war was over). OK, the world isn’t as obstensibly innocent as it once was. However, is it so awful in this wised-up time to long for a little comparatively unknowing lack of guile? Clair’s films may be antiques but antiques are quite often quaint, charming, and of great value…as are this film maker’s works.

4. Man of Aran (1934)

Pretty much any history or text book relating to film history will hail US independent (and how) film maker Robert Flaherty as the father of the documentary form. While it is true that motion picture cameras had been documenting reality ever since their existence began, it was Flaherty who turn the random snippets of recorded life into something with dramatic unity, pull and power.

However, by the standards of later documentarians, he made his films generally a little TOO dramatic, namely by helping reality along a bit by staging many aspects of his films. This is anathema to modern film makers of that ilk but Flaherty was trying, and, despite his very limited output, succeeding, in establishing the form as a viable commercial entity, which allowed its continued existence.

Man of Aran, incredibly his first film of the sound era, is really a stand-in for all of Flaherty’s works. Though his initial effort, 1922’s Nanook of the North, is famed just by virtue of being the first documentary hit, none of his work generates a lot of discussion now due to, in the view of many, being so compromised by their very nature.

Even in its own day, 1926’s Moana was considered lesser due to being a mostly pictorial view of the natives of the South Seas and for being “made to order” by Paramount Pictures. The film maker then tried to go commercial with both 1928’s White Shadows in the South Seas (completed by W.S. Van Dyke) and 1931’s stunning Tabu, which was to be his collaboration with German great F.W. Murnau (who directed most of his last masterpiece before his untimely death).

After having stuck out trying to work Hollywood’s mainstream way (not that it stopped him from trying again with also unhappy results) he struck upon the idea of creating a film dealing with the existence of the natives of the Aran Islands, a most inhospitable groups of rocks off the coast of Ireland in the turbulent Irish Sea.

These islands were so barren that no plant life could naturally grow there (potatoes had to be grown in seaweed!). Pretty much everyone was a fisherman, the wife of a fisherman, or the child of a fisherman as they lived in this chain of islands and the sea was the hub of their existence. However, and this drew Flaherty as much as anything, the place had a majestic raw and powerful beauty, never more so than when the overwhelmingly surrounding sea was all stirred up.

The film maker set out to, and succeeded, in capturing that sublime wonder on film (and no one seeing this film will ever forget the seascapes). He framed this in the context of the life of an average family of Aran. Well, the people playing the family were from Aran but they were absolutely no relation to one another and the scenarios they played out were scripted. Still, it actually plays well. Perhaps if it had been correctly billed as a “semi-documentary” the curse might have been lifted. In any event, this is a true work of art and, whatever its shortcomings to modern eyes, it deserves respect.

5. Dance, Girl, Dance (1940)

Those around in the 1970’s, when film history scholarship first started to become serious, might well remember that, in that era when the Women’s Liberation movement was at its height, there was a lot of feminist film study. Though much of it was centered on how women were presented through the male gaze on film, there was a lot of interest in the work of the very few women of earlier Hollywood (and other places) who managed to direct their own films. No film maker drew more attention than a somewhat obscure and previously nearly forgotten figure named Dorothy Arzner.

Arzner had intended to become a doctor (another mostly male profession at the time) when she drifted into work in the motion picture industry, then in its childhood, and eventually ended up becoming a top editor in the early days of Paramount Pictures.

Paramount was one of the very few film companies which encouraged interesting, individualistic directors and it didn’t seem odd for a woman to helm a film (there had been a number of female directors in the earliest days of film). She remained there from the late silent era through the early days of sound before branching out to such studios as MGM, Columbia, and RKO, making films with, among others, Katherine Hepburn, Joan Crawford,Clara Bow, and Rosalind Russell. (1936’s Craig’s Wife put Russell on the Hollywood map and might well be Arzner’s best film but it isn’t embraced since it adapts one of the most misogynistic majors plays of 20th Century Broadway drama.)

The film which at one time had the attention of feminist historians and authors is Dance, Girl, Dance, which was, ironically, one of the film maker’s last. Made at RKO on a modest budget, it was taken from a story by then-prominent author Vicki Baum (best remembered for the novel and play Grand Hotel) and delt with relationships and aspirations of the main members of an all female dance troup. The stars were a lovely but staid Maureen O’Hara as the dancer serious about her craft and oblivious to popular taste and her opposite number, played by a sarcastically vibrant Lucille Ball, who brazenly sells out at every turn while looking for a rich sugar daddy.

Arzner also had the male director of the troup turned into a rather “gentlemanly” aged lady (not unlike Arnzer herself) played by the great character actress/drama teacher Maria Ouspenskaya. (There was also a token male love interest/bone for the two women to fight about played by Louis Hayward, but that was a very wan aspect of the film.) The big climax, and a scene modern day feminist loved, was an ahead-of-its-time moment wherein O’Hara’s character sharply tells off a rowdy male burlesque audience, which once excited a lot of comment. Why, then, is this film now untalked about?

In his long-time annual guide to movies on TV (and now his classic movie guide) Leonard Maltin, not an unkind reviewer, notes this film’s better points but then makes a statement that could stand for Arzner’s career as a whole: “unfortunately, its not as good as one would like”. Truth to be told, Arzner’s films often had interesting themes and she got some worthwhile performances from, mostly, her leading ladies (not all, though, since a number of them ended up roundly despising her).

However, her record with the actors was rather uneven and, surprising for someone who started as an editor, her films often drag and have a patchy sense of pacing. Like the old joke about the talking dog, the miracle was that Dorothy Arzner managed to have a decent career as a film director in that place and time. Maybe wanting her to be one of the greats is asking a bit too much.