6. Ossessione (1943)

Italy’s Luchino Visconti is certainly one of the cinematic greats period. His most noted films such as 1963’s The Leopard, 1960’s Rocco and his Brothers, and 1971’s Death in Venice will probably be talked about as long as there is cinema and cinema studies. However, he did seem incapable of making a bad film and his debut was no exception. Why, then, is Ossessione so little known and discussed? Well, that’s a story….

Visconti, a true aristocrat both by birth and by right of artistic talent, had apprenticed to the great Jean Renior in France before the war and returned to his native land, worked as an assistant director for a time, and then stepped up to directing as World War II was in full force. His first assignment was a bit surprising: he was given the job of adapting to film the infamous US crime novel The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain, a down and dirty tale of murderous, adulterous lovers in a seedy roadside gas station/greasy spoon.

Hollywood had, at the time, been forbidden by the censor to touch it for a decade and wouldn’t make it until the other end of the 1940s and,even then, in a sanitized version. Now, the reader might wonder how this Italian film company could make a deal to film this book at a time when the US and Italy were enemies in a time of war. Its simple: just like the version made in occupied France a few years earlier, the powers that be decided that the enemy had no rights, not even artistic and financial ones.

This film, in the view of the US was illegal. After the war, it and a number of other films like it were banned from being shown in the US due to copyright infringement. Though the issue was eventually resolved, it took decades and this film didn’t enter into the lexicon of many viewers formative film education.

Past all of that, Visconti’s best known films are noted for their operatic feel and stunning larger than life qualities. Osessione could not be farther removed from many of those qualities. Though he was not thought of as being in the forefront of Italy’s famed post-war Neo-Realist movement, Visconti, at that time, was interested in the gritty drama of everyday, lower class lives and many film historians have cited this work as being either a influence on the then coming movement or (controversially) the first Neo-Realist film (if so, then it had no immediate films which were influenced by it).

In all honesty, it isn’t even that faithful to Cain, but, rather, a pitiless look at the grass roots people of a society in crisis with no moral compass. As ever, Visconti gets top-notch work from his actors, co-writers, cinematographer (who truly makes it look realistic)and everyone down the line. Like its maker, this is a quality item and its a shame that its so relatively little known.

7. Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974)

France’s Jacques Rivette was a bit older than many of his compatriots in the much vaunted New Wave (and, ironically, outlived many of them). This might account for the fact that, despite producing a fine body of work, he rarely seemed to get the level of recognition accorded to his peers. His was the work of a more mature artist (and that movement was otherwise quite youthful) and he also didn’t mind being a bit obscure and deliberate in his pacing with very little regard for length of running time (just see 1971’s 13 hour Out 1 or 1991’s La Belle Noiseuse, a relative short subject at 4 hours).

In a world with accelerated attention spans, that can be a kiss of death. Thus, it might not be that big a surprise that one of his most inventive, entertaining and influential films, the three hour Celine and Julie Go Boating, might get by-passed and not discussed that much.

One thing that makes this work a bit problematic to some is that it is hard to define. Firstly, despite the title, its not about two ladies going on a sailing trip together. No, though there are two young ladies, the boating refers more to their mutual exotic experiences than anything else.

It is accurate enough to say that the plot concerns the two women almost magically taking up together (appropriate since one is a magician) and blurring their individual identities before having a mystical adventure inside an intriguing “haunted” house. Rivette was never thought of as being “fun” or “light-hearted” but this sort of modern version of Alice in Wonderland is a lovely comic reveal on modern women and modern life. Yes, it takes some work to “get it” but most worthwhile things in life do.

8. The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

When the unique British cinematographer turned director Nicholas Roeg died in 2018, he was given a large number of appreciative tributes for his off-beat filmography. This was particularly nice since his career had been in low gear (to be kind) for quite some time. Being around 40 when he finally made the leap to directing, he had been somewhat more mature than most beginning film makers. However, he and the New Hollywood were just made for one another.

A typical Roeg film would combine the striking imagery expected for someone coming from such a visual aspect of filmmaking with an often detached and quizzical view of the world, usually with an eye towards the erotic components of living. He made a stunning debut as the co-director of the wildly perverse Performance (1970) before moving on to his masterful solo debut with 1971’s Walkabout.

He struck gold (creatively at any rate) with the unnerving thriller tinged with sexual intensity, Don’t Look Now (1973) and the sexually intense drama laced with mystery elements, Bad Timing (1980) and the fantasmagoric drama Insignificance (1985), though by the time of the last his work had become a bit erratic. However, his biggest hit at the time of the these excellent early films was a most enigmatic and captivating pseudo-genre piece.

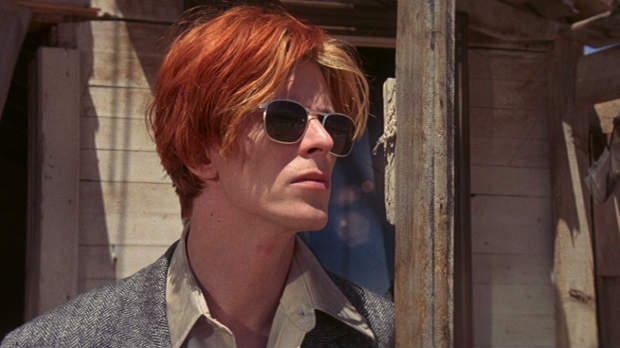

The Man Who Fell to Earth is always listed as being a sci-fi work. Obstensibly, that is correct. The title, which is pointedly double in its meaning, concerns Newton (the great rock star David Bowie in his fine film debut), who literally falls to Earth since he is an alien from another world. He has come to this world on a somewhat vauge mission to get help for his own barren and dying world (which contains his family).

However, his experiences will not turn out well and he will fall to earth in a much more profound way the second time. Though the premise does contain a science fiction element, it has pretty much nothing in the way of special effects and a little in the way of a costuming and make-up. (The viewer is shown Newton in his non-disguised state in only one scene and the film also contains brief glances of the family on the home planet.)

The real thrust of the film is its way of looking at a savage world operating under the disguise of civility and how it defeats those unwilling and unable to rise to the occasion of delivering cruelty in kind. Newton is literally incapable of feeling hatred, anger, or aggressive attitudes. Likewise, the companions he finds on Earth (played by Candy Clark, Rip Torn, and Buck Henry) all live somewhat in the margins of society (and find sorrow and worse when being in Newton’s orbit drags them into the light for a time).

Obviously, this film is more of a hidden character study/social treatise. That is the fact that has thrown viewers from the time of the film’s release (when the idea of Bowie in a sci-fi film was a big draw) to the present. Those approaching it from a genre lover’s point of view are often disappointed (subsequent viewings generally work much better).

The downward trajectory of the film also makes it a hard sell (and it didn’t help that a large amount of footage was cut for the initial US release and not restored until the video era). This stunning looking and edited film with a hugely thoughtful script and interesting characters may well be Roeg’s best film and it surely pointed the way towards more adult and issue oriented sci-fi but it deserves more appreciation and discussion than the limited cult it has developed.

9. Broadcast News (1987)

While many other countries of the world can see work done for the medium of television as just smaller in scale and different in thrust than works done for motion picture screens, its taken the US until just recently to truly start to take down that cultural barrier (and it has largely taken the enormous changes in the tv technology and content to facilitate that).

Sad to say, in earlier times even makers of good television were often regarded as just makers of television who might do something on the big screen if things hit just the right odd way. That leads up to the film maker behind the Oscar winning Terms of Endearment (1983) and the film upon which this entry focuses, James L. Brooks.

No matter what films Brooks has made or what awards they might have won, he will eternally be known as the creative force behind those seminal comic delights The Mary Tyler Moore Show and its offspring (which all look a bit dated now) and The Simpsons (which never will). Its obvious that he loves comedy and his films all show a deft comic touch, even the most serious. Its lovely that he was able to address the elephant in his own room by making a major film concerning television (which is not often at all an affectionate subject in the movies) and mined it for all the humor it contains.

Broadcast News tackles a subject more timely than ever: how the news is delivered to the masses and just how much content those who deliver decide the masses can withstand. This is dramatized by the traumas facing a perpetually nervous, over-achieving, wire-taught female producer (Holly Hunter), who finds that she must favor a handsome and photogenic air-head of a new announcer (William Hurt) over her sharp-as-a-tac but decidedly less attractive old comrade (Albert Brooks), who doesn’t make things any easier by being one of the most resentful and sarcastic people on the face of the earth. That fact that romantic attraction is rearing its ugly head in a triangular relationship among the three is no help at all.

One big thing that doesn’t help this film in the current era is that the face of television news, much like television itself, is changing to a great degree after decades of being essentially the same. With many, many more choices available and the decisions of the old-guard major networks of somewhat less importance than they once were, Broadcast News might well look somewhat dated to many. It also doesn’t help that Brooks enjoyed his moments in the cinematic sun but then seemed largely to retreat back to TV, making him a less than fashionable director to engender discussion.

However, the basic conflict is, as stated, still germane and the acting and interplay of the principals and such wonderful supporting players as Joan Cusak, Robert Prosky, and a terrific cameo by Jack Nicholson as an old and respected news vet, is all still great. Broadcast News might not still be a fashionable film, as it was at the time of its release, but it still has much to recommend it.

10. Beau Travail (1999)

It would be nice to think that the age of sexism has passed (and maybe it is passing) but, to some extent, it does still exist in the cinematic world. Though there are certainly more female film makers in the present day than in, say, Dorothy Arnzer’s time, the proportion is still far from equal as is the acclaim and attention. One wonders if the noted veteran French filmmaker Claire Denis wouldn’t be even better known and her works more commented upon and celebrated than they are if she were a male filmmaker.

Though she has created a solid record of over two dozen films and counting, she doesn’t get the buzz a comparable male filmmaker with such a record might. One further irony is the film out of all her works that is most noted is one that truly betrays no evidence of having been created by a female artists.

Beau Travail is an updated version of US author Herman Melville’s classic short novel Billy Budd (filmed more faithfully and well in 1964). This version is set, not at sea, but in North Africa and the characters are soldiers in the French foreign legion.

The story is told in flashback from the perspective of a suicide-inclined man who once was an officer in this strict and disciplined world and he was in his glory being feared and obeyed. Enter a young man as genuinely magnetic, good, and ultimately beloved by the other men as the officer is hated and loathed. The officer finds this beyond toleration and embarks on a course which will be destructive to all concerned.

Beau Travail is as muscular and vigorous as its characters. Although there is great emotion in it, those emotions are largely held in check and reserved. This is as far from the definition of a “chick flick” as its possible to be. In a chauvanistic environment, perhaps that is why this film, at least at one time, got more notice than other, similarly good Denis films. Perhaps, by that same token, that may well be why this film doesn’t really get the discussion and later day attention that it deserves.