6. Yasujiro Ozu

It’s hard to believe that one of the world’s great film makers was once all but unknown to a significant part of the world but such is the case of perhaps Japan’s finest film maker, Yasujiro Ozu. If one looks to, and reads, older works on film history (such as they were in a time when all too few were being written)it might well seem as if Ozu never existed or, at best, hadn’t done much of anything worthwhile.

That is hard to accept on behalf of the maker of Tokyo Story (1953), Good Morning (1959) or his many masterful films with “seasonal” titles. Why the neglect? Well, Asian films were slow to circulate in the western world for many years due to political strife and cultural differences.

The big breakthrough artist for Japanese cinema, the equally great, if quite different, Akira Kurosawa, was often accused of being too “western” in his own homeland but that was the making of him in the western hemisphere where his numerous action films opened well and gave entry to his more serious dramas. Ozu, quite formal and quite traditionally Japanese, was another matter.

There is no equivalent of 1954’s The Seven Samurai in his canon. His films always deal in matters of typical Japanese life as lived on a normal scale without any of the hyperbole which movies often add. Though his films deal with life in such a specific country, closer examination shows how universal they are in fact.

Thankfully, discerning critics/historians alerted discerning fans who created a demand met by discerning video/streaming companies. Happily, virtually all of Ozu’s 50 plus films are now available to study and/or enjoy. If the cinematic world had nothing more to thank the video revolution for than that fact, it would still be enough.

7. Robert Bresson

Another citizen of the art house world, France’s Robert Bresson made only a dozen films, coming in doses after long spurts of time, in contrast to Ozu’s prolific output, but they do have much in common. While Ozu was warmly humanistic in both drama and comedy, Bresson was quite harshly naturalistic. However, both men had real decency as artists which never allowed them to cheapen human lives and feelings as they are normally lived when presenting them on screen.

Bresson has sympathy but it’s never allowed to interfere which the painful truths of his character’s destinies. This, married to his spare, austere style ensure that his films are always worthy but rather cold in feeling and uncomfortable to many (Kael compared watching 1968’s Mouchette to being administered a beating and knowing when every lick is coming).

It pretty much goes without saying that this is not a formula for box office success (actually, it might well be one for just the opposite result). Many film studies cite such lauded works as 1966’s Au Hazard, Balthazar, 1956’s A Man Escaped, and, especially, 1959’s Pickpocket (to some, France’s finest film), and the cinematic world would be far less without them, but relatively few ever saw them in theaters.

Once more, home video has provided another venue and another chance (though some of the films, such as his later ones, Lancelot du Lac from 1974 being a good example, are often tied up in legal knots due to the complexity of the funding needed for them to be made). Make no mistake, Bresson will never be a popular artist regardless of medium, but home video/streaming has freed his films (among others) from being nothing more than occasional fixtures on an art museum calendar or a lifeless still and paragraph in a film studies book.

8. Michael Powell

Taking a break from the kind of esoteric film makers whose work appeals to specialized tastes, Michael Powell shows that one can be a true cinematic artist and still appeal to a large audience. With his longtime partner, Emeric Pressburger, Powell was one half of a team known as The Archers. During their active years and long thereafter, the two men were deliberately very vague about just who did what on their films.

However, film historians have since ferreted out that Pressburger was the main writer and producer of the pair with Powell being the actual director and contributing writer. That gives Powell an edge in the current director worshiping era but he seemed far less lucky in the years when he was a working film maker.

In 1942 Pressburger won an Oscar for their film The 42nd Parallel (in the now-defunct best original story category), the only one either of them either received. In fact, the only time the Academy ever noticed Powell was with a nomination as co-writer of another Pressburger script, 1942’s One of Our Aircraft is Missing. Not even the best picture nomination for their greatest hit, the much loved The Red Shoes (1948) managed to get Powell recognition for his direction.

Sadly, the success of Shoes caused Britain’s big movie mogul/vulgarian J. Arthur Rank to buy the team’s contract and push them into projects and film making methods which essentially negated their greatest virtues: their originality, inventiveness, rich humor, keen character observation, and fine eye for imagery.

After a golden decade during the war-torn 1940s (featuring The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp in 1943, Stairway to Heaven in 1946, and Black Narcissus in 1947, among others) gave way to a less satisfying follow-up decade (including 1950’s interesting Gone to Earth, butchered for its US release by co-producer David O. Selznick, and 1951’s highly ornate and artistic opera-ballet film The Tales of Hoffman, a later answer to Shoes but not nearly as acclaimed or popular).

The pair parted and Pressburger went into semi-retirement, as did Powell. The difference, however, was the Pressburger meant to go into semi-retirement. Powell’s downfall came with his first big film after dissolving the team, 1960’s Peeping Tom, a truly potent mixture of sexual fetish (voyeurism alined with capturing images of sex and/or violence on film or some recording medium) and crime (the main character is a serial killer) at a time when such topics weren’t common.

It came out just before Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. If it had come after, perhaps Powell wouldn’t have become the pariah of the British film industry as he did, with his past work being negatively reevaluated by those looking for sign of perversion. In this day and time it’s hard to believe that such a thing could happen over what was, in fact, a quite well made and seriously intelligent thriller (though the British have long been squeamish about violence on film). He hardly ever worked again.

Thankfully he had his champions, notably the great modern director Martin Scorsese, who made it a point to push for restoration and distribution of Powell’s work, notably on video. When Criterion was still mostly laserdiscs, he and Powell jointly recorded commentaries for several of the restored films the company released (and, though his contribution was most welcome and valuable, the feebleness of Powell’s voice by that time makes it plain that Scorsese’s help was much needed).

The current film climate is much more favorable for Powell (and, yes, Peeping Tom is now a big favorite on home video) and the newer technologies have rendered him a most deserved second chance.

9. Pierre Etaix

While Powell may have had many of his films thrown in the vault, he still had some that were always in circulation. Poor Pierre Etaix had to witness his ENTIRE filmography being wrapped up in legal/financial limbo for decades! The comic actor, writer, director, and producer was inspired by his fellow French comedic film maker Jacques Tati, in that he made sharply observed, though often whimsical, comedies heavily indebted to the great silent comedy giants.

Like Tati, his films took a long time to develop before filming even started and a long time to get financed, for the films of both, though perfectly accessible, were also for rarified tastes. Thus, just like Tati, his output was limited (6 features, along with a few shorts, one of which, 1962’s Happy Anniversary, earned Etaix an Academy Award, and a very few things for TV).

Happily, he could support himself as an actor in the films of others, for he was a popular performer in Europe, but none of those appearances was in a film the quality of his own. This makes it especially sad that a financial dispute with the company which distributed his films caused them all to be put in the vault from the 1970s until the first decade of the 21st Century!

Thankfully, there were those with long memories who recalled such masterful work as 1963’s The Suitor and his magnum opus, 1964’s Yoyo. Even more thankfully, Etaix hung on until his death in 2016 and saw his films make a comeback. Yes, there was some revival house action, but in modern times that takes place mainly on video and the inevitable releases from labels such as Criterion followed. Just like in a good comedy, there was a happy ending for all.

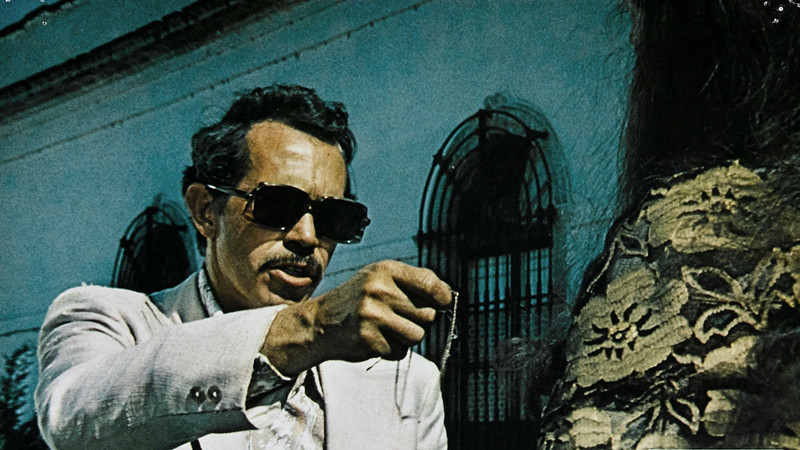

10. Sam Peckinpaugh

One of the wonders of the cinematic world is that it can embrace highly sensitive and delicate artists such as Bresson, comic ones such as Etaix, and rough and ready ones such as Sam Peckinpaugh. His films might be shown in an art house theater now on some progressive day but it would be doubtful that they would have been when his career was in full flower (though it might have happened toward the end of his life when he had become unemployable and, therefore, somehow chic).

If he ever had a sensitive moment he surely kept it to himself and if he ever put one in his films (save for, maybe, his debut, 1962’s Ride the High Country and 1972’s lovely outlier Junior Bonner) it would take a private eye to find it. No, he was, if one will, the poet of cinematic violence, western style.

The surprise is that, for a commercial film maker working in what’s considered popular genres (the western and crime film sector), his filmography is limited. He only completed 13 films (and many TV episodes before his movie period). He started with Ride the High Country, giving western icons Joel MacCrea and Randolph Scott fine swan songs in a film that got good reviews, did good business, aroused no controversy, had what amounted to a smooth production and generally went off without a hitch. That was about the first and last time that happened to Peckinpaugh.

The next time he directed a film it was 1965’s Major Dundee, a film infamous for its production problems, both pre-shoot and post-production. Peckinpaugh was obviously trying to make the kind of film that would routinely come out after the motion picture ratings code system had been put into place but that was a few years away in 1965.

As it was, his next film, his magnum opus, 1969’s The Wild Bunch, came along at just the point when the new system was implemented but that didn’t prevent this opera-ballet of cinematic carnage from almost getting the first X rating, saved only by the deletion of two major sequences. And so it went, for many, though not all, of the film maker’s works. Many still remember the furor over 1971’s hyper-violent (and rather misogynistic) non-western Straw Dogs.

Then there was 1973’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, edited with a veg-o-matic by the studio just to try and make it more commercial and 1974’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, so universally reviled at the time of release. There was also the mater of his last four films, The Killer Elite (1975), Cross of Iron (1977), Convoy (1978), which seems to have been his attempt at comedy, and, finally, The Osterman Weekend (1983), well in the running for the most confusing film of all time. He ended his career making music videos for flash-in-the-pan singer Julian Lennon. Clearly video had its work cut out with Peckinpaugh.

Thankfully, the troublesome physical presence of one of the orneriest men to ever work in films has been removed and now his work can be seen without the filter of personality and it’s quite good. There is a fine version of Ride the High Country out, enabling this almost forgotten achievement to be seen. All but five minutes of the cut footage of Major Dundee has been restored and the score which Peckinpaugh hated so much removed (though who can say if the one replacing it would have been what he wanted?).

Sadly, though an excellent try, this version of the film can’t compensate for all of the difficulties the film endured. The Wild Bunch, though, easily had its missing footage replaced and successfully warded off another attempt to slap an X (now NC-17)rating on it, allowing it to become a great cinematic classic.

Also, good, overlooked works such as 1970’s elegiac The Ballad of Cable Hogue (with fine performances from Jason Robards and Stella Stevens), Junior Bonner, and Alfredo Garcia, and, surprisingly, Cross of Iron, which seem to be getting sharply upturned reevaluations, are now accessible.

However, the best of all may be Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Several years ago, when the film was shown on broadcast TV (remember that medium?), cut footage was inserted to “pad” the film’s running time in order to insert more commercials. It turned out that this was valuable edited out footage and started a number of Peckinpaugh faithful looking to put the film back together.

Thanks to MGM/UA video, at the time the owners and company releasing on video, not one of but two cuts far superior to the released version were made public, one the film maker’s work print version and another a sort of “best of” version put together after Peckingpaugh’s death, which those who worked on it have the integrity not to call his version, but believe to be the best representation of the film.

These versions both have garnered the film far better attention/reaction than the mangled original release version ever got (with the noted film historian David Thomson calling it one of the greats). One could hope that Peckinpaugh would approve but, somehow, it might be best that his take on it all can’t be known or recorded.