In continuing the gold mining for obscure films around the world, and learning about different cultures through their rich artistic expressions, I’ve selected these 10 titles that deserve greater recognition.

1. Volere Volare (1991)

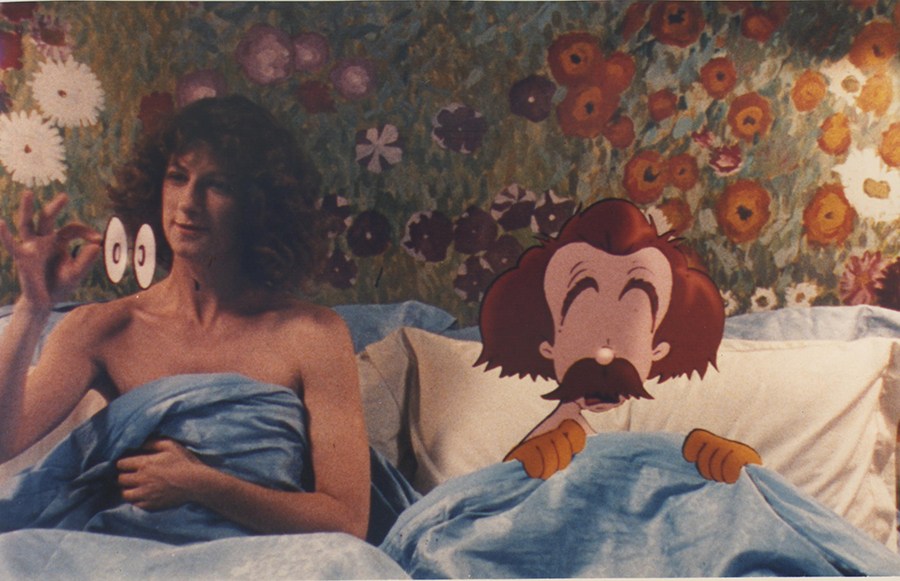

The idea was born after the worldwide success of “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.” The plot is insanely unconventional; he plays a timid cartoon sound, while his brother and partner prefers to take on the voice of erotic productions, summoning women who are wonderful for the work that is performed in the best “acting method of Lee Strasberg.”

Angela Finocchiaro plays an exotic prostitute who takes care of the theatrical satisfaction of her clients, each one more crazy than the other; a sex artist, in the literal definition of the term. The gradual transformation of the sleep sound into a cartoon, a feature that guarantees hilarious scenes, and symbolizes his fear of the possibility of sensual contact with the opposite sex, a concept that falls like a glove in the absurd tone of the script.

Contrary to her ambitious friend who prioritizes wealthy clients, Martina (Finocchiaro) sees her work as a socially relevant mission, since it allows the insane to go beyond her psychopathy, in various levels of dangerousness, in a harmless way for society, an element that it humanizes her greatly.

It’s fascinating to make the traditional happy ending an uncompromising embrace in the surreal, with its fun surrender to the possibilities of sex with the cartoon, rather than the obvious narrative path of solving the bizarre problem. A comedy that would never be released these days, it’s a breath of fresh air in a genre that’s usually a slave to repetition.

2. The Green Ray (1986)

Seldom has loneliness been so well portrayed than by the Seventh Art. Delphine (Marie Rivière, who is also in charge of the screenplay) realizes that it is time to relax on her vacation, but she is definitely not eager to confront herself away from the routine and ritualistic pursuits of her job as a secretary. She cannot keep up with the boys for fear of giving.

By looking away from her reflection in the mirror and trying to find a meaning for its existence in the external world, the girl does not see the various flirtations she attracts, believing herself to be increasingly uninteresting. Unlike the usual protagonists of the director, she speaks little and clumsily, because (as she says) she has problems expressing herself. The act requires surrender, the “lowering of shields”; in short, everything she fears.

By staying aloof from all social conventions, it becomes a pure element, which does not feel adapted to the corrupt world in which it believes to be inserted. It is not by coincidence that, in the end, it reveals the book that she spent the entire movie reading was “The Idiot” by Dostoevsky.

Delphine only intends to modify its “modus operandi” when finding Lena, an uninhibited Swedish girl, its perfect antithesis. The genius of the script insinuates itself at this point, when we begin to question whether we really want to see the protagonist finding a boyfriend. Is not it right that we should twist her out of apathy and impose herself in life as a human being? As we direct our desire to meet the comfortable satisfaction of a social ritual with any stranger, are we not disrespecting her as a woman? Do we want Delphine to become Lena?

In the brilliant third act, we began to understand the protagonist’s point of view, her aversion to the limiting roles that society imposes on women. And then, in a touch of pure sensibility, Rohmer makes us admire the meteorological phenomenon of the “green ray” on the horizon, which, at the moment (in the eyes of the writer Julio Verne), causes the person to magically see their feelings and those of others. She then, as she had not done before, smiles with the naturalness of a child who sees the world for the first time.

3. The Condemned of Altona (1962)

Industrialist Albrecht Von Gerlach discovers that he is close to death and names his son Werner (Robert Wagner) as his successor; Johanna (Sophia Loren), his wife and actress involved in a work of Brecht against Nazism, discovers the secrets of the family.

Unjustly little known, including among fans of Vittorio De Sica, although he received for it the “David di Donatello” award for Best Director. Adapted from the penultimate piece of Jean-Paul Sartre (quite faithfully, except for the option of including outside scenes, outside the confinement), unique in that he directly addresses Nazism in a clever and daring criticism. Sophia Loren, Fredric March and Maximilian Schell act boldly in roles that completely ran away from what the public was accustomed to, ensuring a still more somber mood to the project.

It recalls, in tone and complexity, the works of Polish writer Günther Grass, among them, the most famous: “The Drum.” The idea behind a young Nazi who is kept, years after the end of the war, imprisoned in an attic by his father, without any communication with the outside world, so that he does not perceive reality, causes shivers just thinking about it. The excellent ending, which I will not reveal, contains one of the strongest cinematic images of that decade.

4. The Eighth Day (1996)

The impact of the tenderness of the young man with Down syndrome, Belgian Pascal Duquenne, on the hard bark of bitterness of the impeccable Daniel Auteuil, who perceives his family to be more and more distant, in the beautiful moment where the boy tries to block the tears of his friend as he built a smile with his fingers on his face. Their reunion in the rain, the reassurance of friendship, after a cruel attempt at forced detachment.

The compulsive worker who, through this relationship, learns to be a better father to his daughters. The deceased mother who, to the sound of her idol in music, appears to affectionately comfort the young man’s anguish. And these scenes, which could easily fall into exaggerated finesse, are magnified by the sensitive way director Jaco Van Dormael chooses to be content with minimalism, with the protagonist having a clear, emotionally independent attitude, dispensing with the compassion of others.

The plot addresses the young man’s desire, hospitalized in a specialized hospital since his mother’s death, to return home. He is a burden too heavy for his family members, who are selfish people and who do not want to face the visually different reflection in this disturbing mirror, as studied by the French psychoanalyst Pierre Fédida, characters that symbolize the way a large part of society views the disabled, the apparent lack of interest in the necessary social inclusion.

This rejection that speaks directly to the disorienting clash of the different in contact with the image that represents the initial formation of the unconscious “I”, or in the words of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, that ideal “I” in which we recognize, in reality, a wrong view that does not correspond to the fragmented body we experience. The boy’s quest, in this charming road movie, for the concept of “going home,” reflects the exhaustion of hope in this narcissistic society. The purity of it, in the end, sacrificed as atonement for the sins of the world.

5. The Killing Machine (1975)

When talking about Sonny Chiba, many remember his work in the trilogy “The Street Fighter,” but I consider that his best moment, as a martial artist and actor, a rare opportunity that he had to build several layers upon, is in this little known pearl, directed by Japanese director Norifumi Suzuki, with a screenplay by Isao Matsumoto, which approaches the real life of Doshin So, founder of Shorinji Kempo, from his traumatic childhood, through the time he was a soldier in the final period of World War II until he became a master. Chiba was his apprentice, so you can imagine the emotion he felt in defending the character on the big screen.

The tone is heavy, tuned in the tragic dramatic tuning fork, reflected in the way martial technique is used, with brutality and generous doses of gore, dominating by rotational wrist locks, the honoree’s specialty. The castration scene of the rapist is remarkable and cinematographically powerful, but what remains after the session is not the strings of struggle. I do not remember another film of the genre that works so effectively on the question of the importance of the martial arts discipline as an inspiring and transforming force in the lives of young people, helping to overcome obstacles and form noble characters.