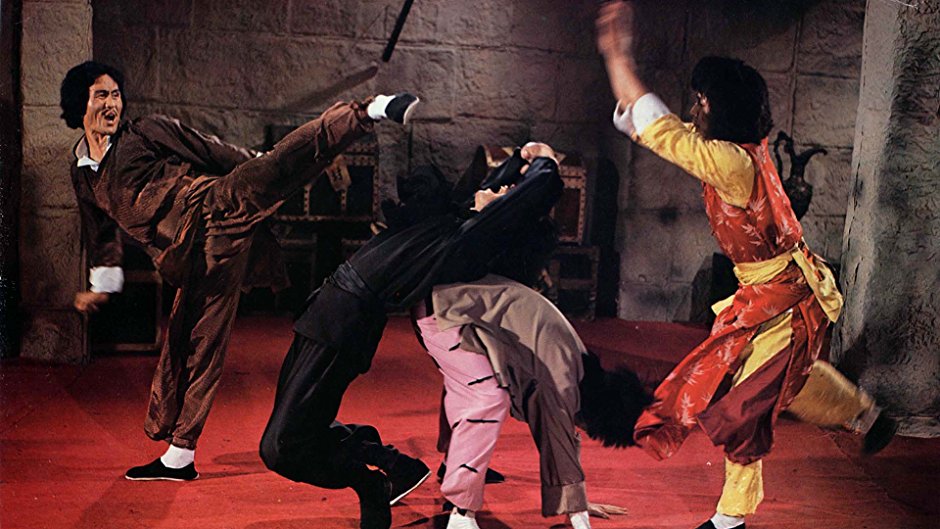

6. The Loot (1980)

A highly creative independent production that made the industry turn its eyes toward its director, Eric Tsang, who received warm praise from various martial artists of the day, such as Jackie Chan, who invited him to direct with him “Armor of God” released in 1986. Just because the plot does not involve a revenge affair, it already deserves honorable mention, but the structure adopted from Agatha Christie-style police novels, combined with the comic sense that follows efficient, guarantee high quality entertainment, even for those who does not appreciate the genre.

I consider this to be the best moment for David Chiang as an actor, playing a bounty hunter / researcher who goes into a dispute with another mercenary (Norman Chu) for a common purpose: to find the enigmatic jewel thief and killer known as “Spider.” It is interesting to note that the script becomes even more interesting in revisions, but the revelation of the mystery does not weaken the experience.

The last 20 minutes are, without exaggeration, brilliant stunting with technical class and timing, with the confrontation between Chiang, Chu and Phillip Ko, with the first using the monkey wrist strategy, inserting a hilarious touch, the dread shake. And in conclusion, a brave debauch with a dramatic visual cliché used in the productions of the Shaw Brothers studios.

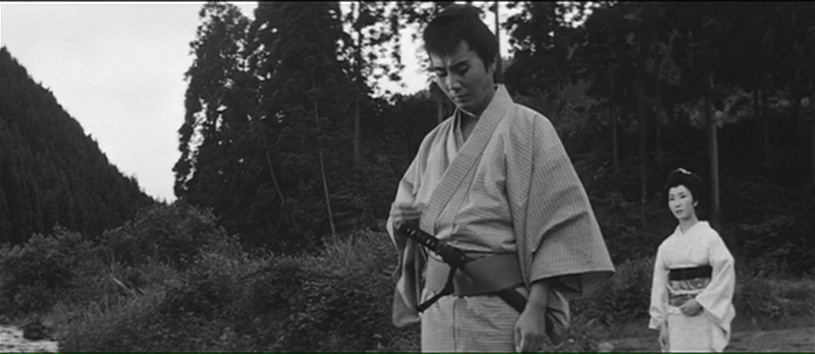

7. The Betrayal (1966)

Director Tokuzo Tanaka had no appreciation for the thematic grandiosity of Kurosawa, or interest in the philosophical ramblings of Ozu, being closer to the kind of approach Mizoguchi and Kobayashi took. As the assistant director for Kurosawa and Mizoguchi, he drank from the best possible sources in his area, using his technique in favor of chambaras made by Daiei studio. He is known only to those most dedicated fans of the genre for his work on the Zatoichi series, but his undisputed masterpiece is “The Betrayal,” a remake of “Orochi,” directed by Buntaro Futagawa in 1925.

Seiji Hoshikawa’s screenplay is a frantic rhythm, with the first two acts dedicated to the meticulous development of the characters and their motivations worked in long dialogues, with the action reserved for the climax. Intense action scenes that prepare for the final battle, praised fairly as one of the longest and most brutal in the genre, where we watch the character played by Raizo Ichikawa, an honorable samurai who is unjustly accused of a crime, fighting alone against more than two hundred warriors.

And if the plot avoids to deepen, for example, the friendship that forms between the exiled samurai and the thief who stole his wallet, it compensates for one of the most shocking moments, not only of the chambaras, but of the action movie genre as a whole: the time when the hero, exhausted in the long final combat, must force his fingers to release the tsuka / handle of his broken sword, so that the confrontation can continue.

It is distressing to see the body go beyond the limits; it becomes dehydrated, it seeks to quench its thirst between an elusive and another. It is not only a struggle, it is loaded with symbolism, the epiphanic transformation of someone who is aware that he has lost everything, moved only by his character.

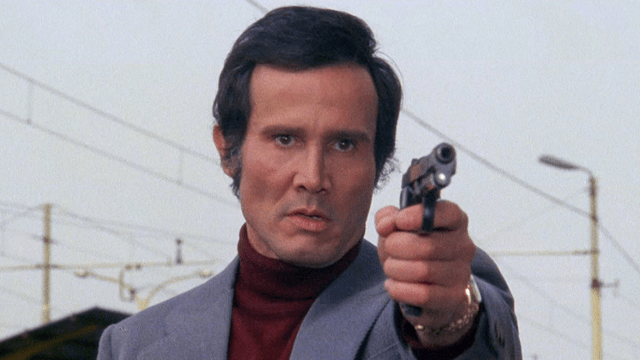

8. Almost Human (1974)

Umberto Lenzi’s masterpiece: “Milano Odia: La Polizia non Può Sparare” is a classic poliziotteschi that I consider superior to his most celebrated work “Roma a Mano Armata,” released two years later. The script is by Ernesto Gastaldi, who last year wrote Tonino Valerii’s unforgettable “My Name Is Nobody,” working on the idea of Sergio Leone, and years later he would help Sergio Martino in the great giallo “Torso.”

Cuban man Tomás Milián, at his best, plays a mediocre and insecure thug who finds, in the possibility of kidnapping a young daughter of high society, the chance to prove himself competent. And to make matters worse, his intention is clear from the start: he wants to get the ransom money and kill the girl. It is not only for the money; his war is personal against the system that, in his distorted mind, elects the lucky and the unlucky ones.

For him, the police class is weak, easily corruptible, limited to following the law. Sadistic, even the comrades question this radical position, with the awareness that they themselves can become targets of their anger. He just did not expect to find in his way the most hardline inspector in town, played by Henry Silva and his face cut to chisel, someone who discovers that the only way to win the case is to become crazier than the thug, the cool moorings.

The tone is heavy, the level of violence is high, the script makes no concessions, following the line of Michael Desire’s “Desire to Kill,” released that same year. And it is worth emphasizing the spectacular soundtrack of the master Ennio Morricone. Great work that deserves greater recognition.

9. Raquel’s Shoeshiner (1957)

In the mold of his most famous admirer, Charles Chaplin, Mario Moreno was able to balance the laughter with tenderness very well, as in this one, which is one of his best films. Although, as something usual in his filmography, many jokes get lost in translation, like the joke in the title, involving the work of Maurice Ravel and the activity of the protagonist, a Bolivian trambiqueiro (shoe) that falls in love with a teacher, played by Manola Saavedra; it is impossible not to be enchanted by the improvisations of the actor. When Cantinflas releases his nonsensical, famous “cantinflear” machine gun, you need to direct your attention to the interlocutor, who strives not to ruin the footage by smiling out of time.

In his first color work, shortly after winning international fame and the prestige of the critics with the award-winning “Around the World in 80 Days,” the Mexican filmmaker proves to be at the peak of his inspiration, especially in the hilarious first hour, where we witness an uplifting history lesson he provides to a foreigner, and to display, in a state of complete sobriety, all the discretion and elegance that should be the standard at funeral ceremonies.

It shows that what really matters is to console the beautiful widow and offer a friendly shoulder to all the women present in the ritual. And, of course, being such a worthy man, he was left with the responsibility of taking care of the dead son of the deceased compadre, a laborer who, as Cantinflas explained, went to heaven after quitting the asphalt, having fallen from the building where he worked.

The most famous scene, his boldness as a dancer, is very nice, but the moment that remains in my mind is the silent reality shock of the character, after the sad farewell of the child, clinging to the colored ball as symbol of gratitude for the company of the boy, who fought so hard to be able to pay.

Cantinflas is carried by the emotion transmitted in his eyes, a scene that refers us to the payment of the treatment of the blind florist of Chaplin in “City Lights.” Like the English wanderer, the Mexican peladito learns that kindness is a noble act that does not demand reward, does not need recognition, it is only the feeling of happiness that happens to tear, the verification of the genuine affectionate intention of those who the offers.

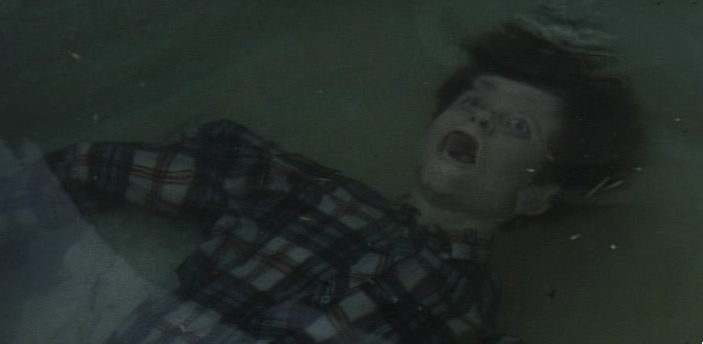

10. Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972)

This is one of those films that, two minutes after the end, while still recovering from the impact, you feel like cheering up. Lucius Fulci, a notorious director, managed to create a brave single treatise on thorny topics such as prejudice, pedophilia, hypocrisy, superstition and religion, without fear of controversy.

I will avoid revealing much about the plot, which is a tremendous disservice, especially in this case. In a village dominated by mysticism, children are murdered, leading the policemen to a voodoo witch played by Brazilian actress Florinda Bolkan. The script opens the range of possibilities, showing that all are suspicious, since there is no sign of any sense of morality or ethics in the attitudes of the residents.

Even the children, who end up being victims, are presented practicing acts of sadism without any trace of empathy. The only one who is pure and well-meaning is the priest. One of the characters, played by the beautiful Barbara Bouchet, is a drug addict who seeks rehabilitation, a daring young woman who seems to have a fixation on insinuating herself sexually for the boys of the region.

What is most interesting is how history subverts any expectation, including, visually, a characteristic symbolized in one of the most interesting scenes in the history of giallo; truly unforgettable, a brutal lynching accompanied on the soundtrack by the exotic programming of a radio station, in its dramatic summit the beautiful composition of Riz Ortolani: “Quei giorni insieme a te,” sung by Ornella Vanoni. The impressive sequence gains even more epic and poetic airs under review, knowing the outcome of the plot.

Author Bio: Octavio Caruso is a Brazilian film critic and filmmaker, you can find him on https://www.facebook.com/cinema.octaviocaruso/.