Away from the bustling streets and shiny purlieus, you could come across the most charming silent corner in a dark, lonesome alley. Lying unsung under the heavy shadow of the old classics, your favorite book could be found on a dusty shelf of an old bookshop. Even, right next to Louvre Museum, in the hands of a street artist, your eyes could linger on a real masterpiece.

All cinephiles love the unforgettable classics that the “enfants terrible” of the seventh art have signed. The filmography of Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Federico Fellini will always claim a place among humanity’s greatest works. Nevertheless, all cinephiles love overlooked films that once watched on a festival or in a local cinema hall, keeping their frames in a personal cell of memory.

Their creators’ names haven’t been written with gold letters. Still, the following artworks may reveal to your eyes a personal all-time classic.

10. The Ascent (1977)

World War II was undeniably one of the darkest chapters in human history’s book. As a reality’s mirror, cinema has exposed a wide part of history in its entire shape and depth. For instance, Elem Klimov’s “Come and See” is one of the most unforgettable and striking pieces that translates the horror of cold war into the language of cinema. Yet, among the unheard Soviet filmic masterpieces lies “The Ascent” by female Ukrainian director Larisa Shepitko.

In a freezing-cold rural area of Belarus, two communist partisans head off on a vain quest for food through the monotonously snow-capped desert of a land. Soon, Sotnikov and Rybak realize the predominant presence of their enemies, as they progressively move forward into the sanctums of a both esoteric and cosmic landscape. Representing the two opposing poles of a conscience, the story’s protagonists are essentially confronted with enemy that occupies their soul.

Shepitko’ s unplanned epilogue of “The Ascent,” the last fruit of a brilliant yet short career that was abruptly finalized due to her immature demise, is one of the best works of Soviet cinema. In a stunning frame of existential voids and soulful portraits, Klimov’s wife accommodated a simultaneously realistic and allegoric reflection of a humane loneliness, posting painful questions that gently strike the most irritable chords of a mind.

9. Rebels of the Neon God (1992)

Ming-liang Tsai is a key director for those being familiar with the Taiwanese new wave cinema. For the rest, his work perhaps remains in a distant glory. Tsai’s most discussed creations on international level include the silent chaos of “What Time Is It There?” and the cinephile misery of “Goodbye, Dragon Inn.” Here, a sunray will vibrate the faint shade of melancholy that enshrouds his first feature “Rebels of the Neon God.”

Like Lukas Moodysson’s characters, the teenagers of this story seek attention in a paradoxical way that adults fail to comprehend. Surviving under the gigantic ghost of modern Taipei, a group of disoriented adolescents search for an existential purpose in the confined tract that their huge city’s web defined for them. But the ignorance of those constant eyes that intentionally avert their gaze, immerse the exposed panhuman young creatures into an abyss of anger and tacit loneliness.

Tsai’s cinematic language respects the stiff pace and bleakness of reality. In its unvoiced woe and thematic plenitude, his picture fluidly delivers the quintessence of the realistic setting and characters it elaborates on. “Rebels of the Neon God” very organically probes the decaying core of our modern world on an urban landscape of disperse alienation. Arguably, its daily stark pain will carve an aching scar in your heart.

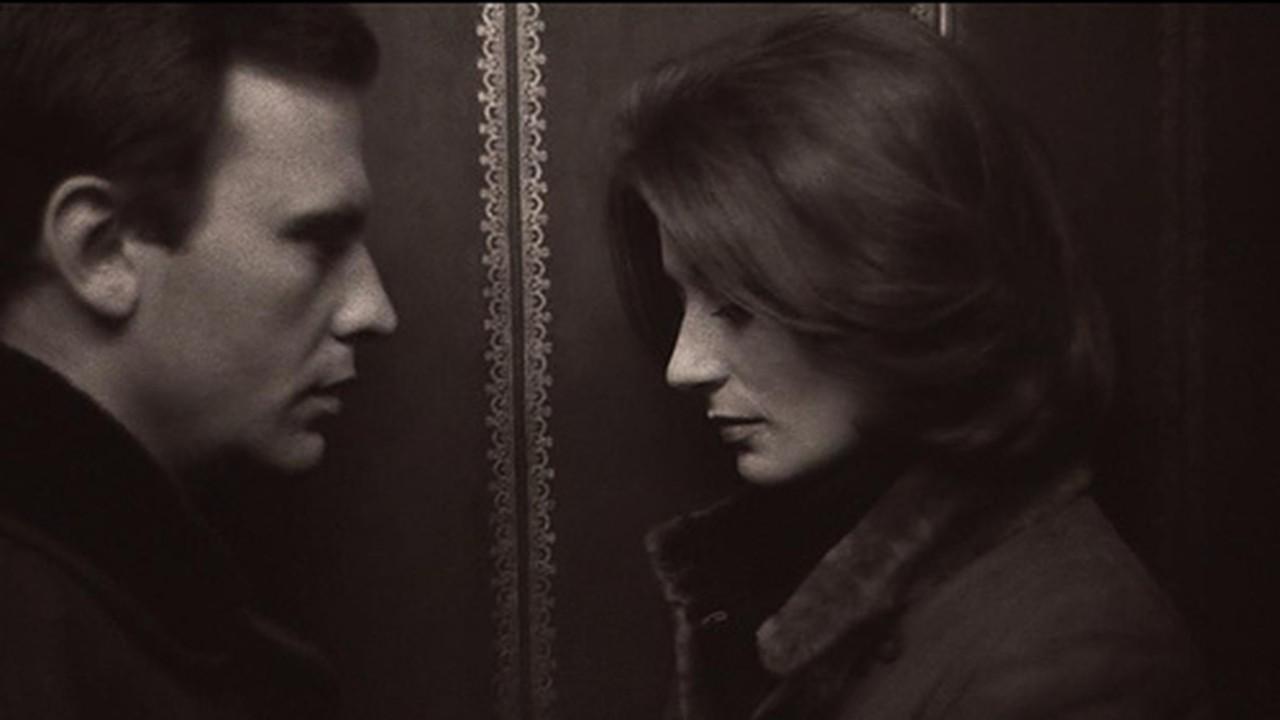

8. A Man and a Woman (1966)

Related to the French New Wave, Claude Lelouch is a director of a long-lasting and prolific career. Among the numerous pieces of his artwork, his 1966 “Un Homme et Une Femme” is the one that has stood out, winning two Academy Awards in 1967. Nowadays, more than fifty years after its release, the movie lies in obscurity. However, its grace effortlessly appears to every unexpected viewer.

The plot involves the springing romance of a widow script girl and a widower race driver. They are both dedicated parents, inhabiting a transparent hideaway of yesterdays. But ever since they meet each other, a vivid longing for sentimental awakening overwhelms their days and thoughts. The significance of this simplistic conceptional scheme is pointed out by Lelouch’s exceptional visual synthesis and narrative terseness.

Stories are told again and again, and their meaning resurfaces from one’s subliminal sheds through various different canals. In this fashion and since cinema is its own language, the most important element is the story’s exposition. Lelouch, filtering his story through many deforming lenses, creates a sustained visual imprint of sentiments. At the end, the well-crafted and groundbreaking cinematic entity of “Un Homme et Une Femme” manages to be an unheard masterpiece.

7. ‘Round Midnight (1986)

Occurring as an American-French collaboration, Bertrand Tavernier’s “’Round Midnight” is an effective endeavor to portray the devastating inner turmoil of a jazz musician who intended to discover his real self by rejecting its darkest aspects. Rooted in the most genuine sentimental bedrock, the picture is a cinematic dedication to music as a means of self-expression and as a personal escape hatch.

Self-destructive and addicted to alcohol, Dale Turner is a jazz musician that is sent away from both his job and home. Ineptly balancing between shattering and brilliance, he decides to collect his pieces and move in Paris, where he gets a job in a bar.

There, a poor fan observes Dale’s remnant reshaping every night in the center of a melodic swirling. Moved by Turner’s obvious solitude, the observant Frenchman offers him what he never had: a friend willing to listen and sympathize.

The role of Dale Turner is embodied by real jazz musician Dexter Gordon. Although Gordon isn’t an actor, perhaps he supplied the role’s requirements even better than a professional, since the burdens of a musician’s life are well-kept in his heart. His performance informs that music is a charged wire that connects the creator and his world, whereas it also stands for the glassy wall that detaches them. Music is liberty and prison at the same time. “’Round Midnight” is a mere explorative step in a musician’s pathway toward a place of concurrent sharing and isolation.

6. Man of Iron (1981)

The documentary-style film “Man of Iron” by Polish director Andrzej Wajda attempts a bare observation on a resent troublesome past and a bitter personal comment all the same. Entailing footage of real events that took place in Warsaw during the 60s and exposing the director’s perspective toward the political and social stage of the era, this overbold cinematic statement won the Palme d’Or price of the Cannes film festival in 1982.

Reformulating the case’s picture, the story develops around a journalistic coverage of the historic shipbuilders’ riot in Gdansk. As a disoriented reporter visits the shipyard in order to fulfill his task, not in terms of professional impartiality but as a plant force, the leader’s background is unfolded through a series of flashbacks. Being more and more lapsed into the obscure object of the revolutionist’s past, the reporter develops a preoccupied interest on the current political circumstances.

“Man of Iron” visits its territories with the aim of providing a wide and descriptive portrait of the factual socio-political conditions in belligerent Poland. Exposing the situation’s essence through his global consideration and inserting prominent documentarian elements, Wajda intends to approach the truth as close as possible. Perhaps an impartial conclusion is impossible to be drawn by the viewer’s part but undeniably, this piece is a historical source of great significance.