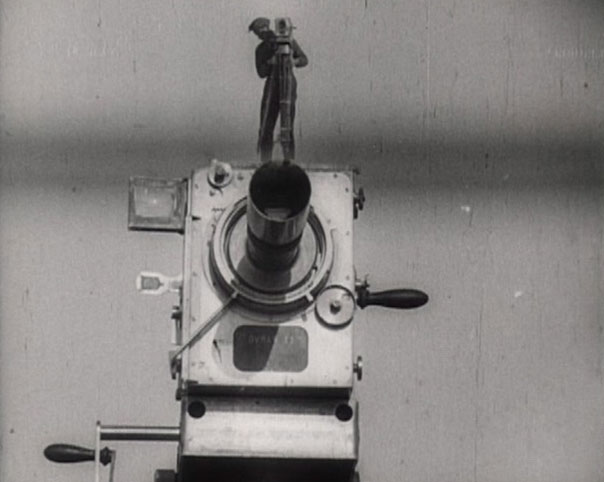

6. Man with a Movie Camera

When people talk about the natures of film editing, the name Dziga Vertov is likely brought up. Of course, Vertov changed the ways we shot the world (and the ways we released our results through editing, too) with Man with a Movie Camera. What’s still incredible is how different the film continues to feel today nearly ninety years later.

Man with a Movie Camera may be the greatest documentary of all time, because it champions everyone and everything. It puts athletes on the same pedestals as it places factory workers. If you are captured, you are important.

Are these figures important in their own lives, or in the grander scheme of things? That’s up to you to decide. Vertov proves that film has the potential to elevate any subject you can ever think of, and you can think about which cases work the most (if you are that picky enough to be reluctant towards the entire film).

7. The Marriage of Maria Braun

It’s normal to see the counter arguments for any event in a film, but Rainer Werner Fassbinder utilizes all two hours of The Marriage of Maria Braun to depict everything but the actual act of ceremonial unity. The titular character marries a soldier that has been reported as killed in action (all of this after an unusually explosive opening scene). Maria moves on, but Hermann returns to the scene of their vows being betrayed.

With a stilted relationship between the two, The Marriage of Maria Braun is the progression of both people when they are away from one another. We get to the climactic ending (one of the greatest feats in Fassbinder’s career), where a series of revelations and a shocking finale get paired with the sounds of a sporting event. When the title gets pasted on the screen, that’s when you realize that you truly did witness a marriage: the marriage between a subject and its audience (us), because it existed more than her own with her husband.

8. Playtime

This lengthy comedy is almost a reincarnation of the great silent pictures by Chaplin or Keaton. You focus so much of your attention on what visual gags you can find. In fact, Playtime is so complicated in its arrangement, that the film almost becomes a “Where’s Waldo?” of hilarious images. You get blatant examples, like the collapsed doorknob being held in place to mimic the invisible glass door that just shattered seconds before. If you don’t get distracted by this joke, you may find something lurking in the background.

With a barely-existing story, the immense lack of important dialogue, and the film being divided into six settings, Playtime is literally what its title suggests. Here is your escape for the evening. You are challenged to find as many off kilter things about it as possible. Perhaps your attention to detail for any other film will exponentially grow after this idiosyncratic exercise.

9. Viridiana

Stop the presses! Luis Buñuel made a film that challenges cinema? Well, you can pick so many examples in Buñuel’s career, but to go with something different, let’s pick Viridiana. It’s appropriate that the central character is a practitioner of religion, because the film drifts from normalcy to unorthodoxy relatively quickly. The deeper into this girl’s story we go, the more twisted it gets.

Naturally, the film’s structure begins to collapse into something a little bit more surreal. By the end, where shots become tableaus of famous paintings and fourth walls are broken, Viridiana is no longer your average drama. Aside from Buñuel’s weirder works, Viridiana is a great example here because it tricks its audience into thinking they are in for one ride, when they really take a detour towards something much more different.

10. Woman in the Dunes

We end off on this Japanese New Wave gem that focuses on the maximalist uses of setting and the minimalism found in story. The film is easily a considerable example for how cinema can create new forms of folklore and mythology. Here is a teacher that goes on a trek to discover more insect species in a desert; his leisure traps him in a permanent state of limbo. Try as one might, the physical or mental will to leave is forever changing.

Woman in the Dunes is an exploration of one’s perspective on their situation, as the rotating feelings of one’s predicament dictate more than actual events do. Here is a reminder that a film does not have to strictly be linear, as the implications at the end of Dunes leave us with the sensation of a circling permanence (a cinematic Ouroboros).