6. Saving Private Ryan (1998)

Steven Spielberg using handheld camerawork for an entire film was definitely a choice. He could have shot and at the time probably received the budget to match a more classical, traditional war film reminiscent of the American 1960s and 1970s. But Spielberg wanted an immersive experience that puts the viewers in Normandy themselves.

Aided by regular DP Janusz Kaminski, the film uses a wide variety of handheld shots from tracking to over the shoulder shakily to simply following a character. Spielberg stated he “wanted the camera to vibrate, with the image shaking to closely match the Robert Capa photographs of Omaha Beach that morning . . . to capture that chaos.” He managed to achieve that intensity for the entire film.

If the film was shot with sweeping, pretty picture shots that a lot of other filmmakers would have been tempted to do, the film would have suffered. It made the experience so frighteningly accurate and intense. And when do actors like Tom Hanks and Matt Damon have a handheld camera so close? Can’t think of anything that resembles or even comes close.

Sometimes, even the biggest filmmakers want to use handheld camerawork to tell their story. And when they do, they can achieve an experience no others can replicate.

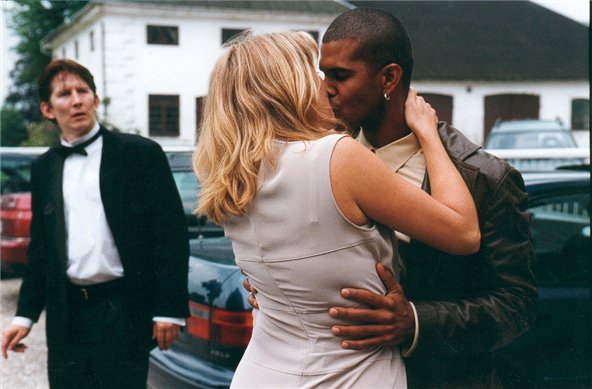

7. La Promesse (1996)

The breakthrough film for Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne was shot entirely with handheld cameras, as is most of their work. The film explores many themes that they revisit often such as morality, conscious, fathers and sons, and choices by the protagonist, but it’s through their aesthetic that these themes rise to the top.

The film revolves around teenage Igor, played Jeremie Renoir, as he feels morally responsible to care for a family of a recently deceased worker, against his father’s wishes. The handheld approach shows the fragility of Renoir as he goes from childhood to adulthood.

The duality of both worlds as he continues to spy on the family and sings with his father at a bar are captured with this approach, so it’s hard to diffuse where the character’s choice truly lies. We become eager just as the camera becomes eager as it floats next to his face in extreme close up – what is he thinking?

The Dardenne brothers somehow manage to make their world seem so tangible to viewers as we are right alongside Renoir as he navigates a grey, muddled world. We become spectators in their native Belgium, pondering over what is the right choice. What path will Igor choose? It results in constant tension and gripping filmmaking as the loose camera just makes it that more authentic.

8. Gomorrah (2008)

A film so realistic in its portrayal of the mob in Naples, the co-writer of the film and author of the novel Roberto Saviano has been living with police protection ever since. But it’s Matteo Garrone’s assured direction that brings it to life.

Garrone follows the lives and situations of several people, from wannabe gangsters to tailors to sanitation workers. The style of the film never changes as it is shot in a documentary-like fashion. But what makes this entry different from the others is the epic scope and diverse characters. Gattore helps us see the world of the Camorra and their various dealings amongst Italians of all backgrounds and ages.

We watch with the same intensity, shock and awe as a 13-year-old boy is recruited into the world, as an an old tailor trying to make some extra dough is literally in a life or death situation. The documentary approach literally makes us feels like we are watching a documentary because we learn what happens behind the curtain and are exposed to a world we never saw, read, or heard of before.

Garrone’s choice of aesthetic achieved a stunning result – a brilliantly acted and structured film with realism that no one has ever witnessed before.

9. The Celebration (1998)

The first film of the Danish Dogme 95 movement started with a bang. It obviously goes along with the rules of Dogme 95, such as, “The camera must be hand-held. Any movement or immobility attainable in the hand is permitted.” Out of this, Thomas Vinterberg created what Ingmar Bergman called “a masterwork.”

Since most of the traditional rules of filmmaking were tossed out the window, Vinterberg could simply focus on characters and story, in the same vein of Cassavetes. And with only handheld camerawork using a Sony DCR-PC3, he could go anywhere.

For example, he puts the camera under desks and shoots upward, or the camera gets so close to the actor’s eyes that they literally back away. The handheld-ness also adds to the tone of the family as we go from a light-hearted comedy to a family gathering with a sinister, dark, unsettling tone. The camera’s constant movement corresponds with our own inner shakiness of what is actually going on and what secrets are being revealed.

Even if the film wasn’t Dogme 95 and shot with static and controlled camerawork, the result would have been stiff and distant. Yes, we would still have been surprised and appalled by the plot details, but with handheld, we were closer to the action and feel like we felt a bit of celebration for the film experience.

10. The Wrestler (2008)

After a divided response to “The Fountain,” Darren Aronofsky stripped away all elaborate production design, studios, and style, and he got down to fundamental filmmaking. What resulted was one of the best performances of the 21st century by Mickey Rourke, and a film that is still felt long after the credits have rolled.

By having a handheld approach, you get several things. We are able to track behind Rourke as this broken man walks from backstage to the arena to the back area of a food market, the feeling of being inside a turnpike dirty wrestling ring, and intense relationships in suburban homes and strip clubs.

The camerawork isn’t trying to do anything fancy or stylized, and is not going for a documentary approach, or aiming to be something it’s not. It’s just doing what a motion picture camera sets out to do – capture people in motion. And the film simply and quietly observes these characters and people. And out of that realism, a world is born and we see film as that feels like a cold post-holiday January or grey November day.

If the film had stylized camerawork other than handheld, it would have been to stylize the wrestling action scenes or play for melodrama on scenes between Rourke and Marisa Tomei or Evan Rachel Wood. Instead, we get a powerful, character study of a man and to simply put it, a beautiful film in handheld form.