6. The Marriage of Maria Braun

The works of Rainer Werner Fassbinder never went anywhere, but a good chunk of his greatest achievements are being worked in to many curriculums as of late. In that breath, let’s give some scholarly kudos to The Marriage of Maria Braun: the first of the BRD Trilogy. It’s a very straightforward film in an expressionist sort of way, and it would be a refreshing take on that kind of filmmaking style.

Where Maria Braun truly shines is with its daring use of combining images and sounds (sometimes in an unconventional way). An example is the brilliant ending that pairs a shocking conclusion with a completely irrelevant sound to deliver something that’s impossible to describe.

Werner Fassbinder was a filmmaking genius, and I don’t think the case studies should stop at a select few of his works. The Marriage of Maria Braun is one of his less daring works, but a great instance where Werner Fassbinder used his expertise to power even the bare basics of filmmaking.

7. Sawdust and Tinsel

Who hasn’t studied Ingmar Bergman in university? The Seventh Seal is almost a Film 101 mandatory staple. Persona has been celebrated within the new millennium, and thus reassessed many times over. Summer with Monika is poetic yet rebellious, plus an infamous film in cinematic history. Many of Bergman’s other works get shown in the spotlight through their different relations to these (and other notable) works.

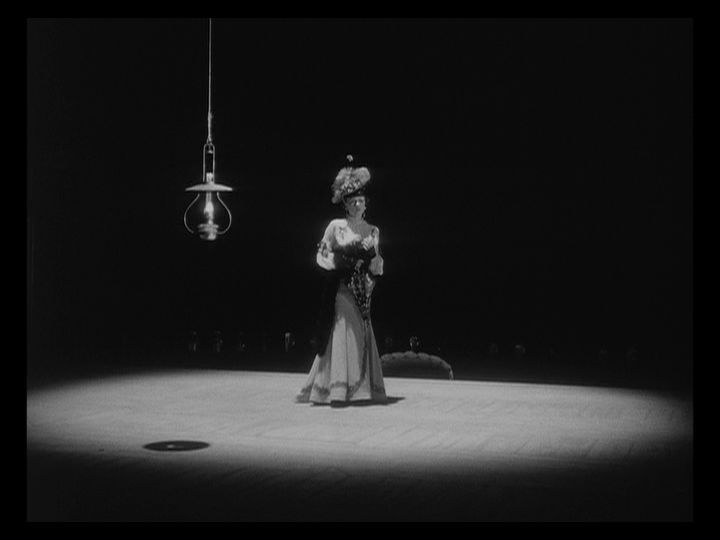

One film that is unforgivably forgotten is Sawdust and Tinsel. It’s the first collaboration between Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nykvist, so you will see many shots that are ahead of their time (including creative mirror shots, first person perspectives, reflections and landscape images).

It’s also around the time Bergman was getting really good with crafting metaphors, as the struggling traveling circus here is a great representation of the struggling working class chasing the American dream. It’s as literary as Summer with Monika, but with a tiny bit of a taste of the aesthetically-prone works of Bergman’s filmography.

8. Ugetsu

The importance of Japanese cinema is always reflected upon in film school. The correlation between Japanese and American films is for a whole plethora of reasons; mainly, both industries had filmmakers that were influenced by the other’s works.

Notable examples include Akira Kurosawa trying to put a spit on American westerns with his samurai films, which inspired Italian director Sergio Leone to turn these back into spaghetti westerns; these latter films subsequently affected how American westerns were made from thereon out. That’s all obvious.

What can be overlooked is the work of someone like Kenji Mizoguchi, and his best work Ugetsu. It’s gorgeously shot, and laced together with poetic storytelling. It has resonated with critics since its creation, and has been seen as a piece that resonated more within American cinema than in Japan (initially, anyways). This is the perfect link in between. It’s so heavily discussed. Why have I never seen it being taught in class?

9. Viridiana

What good’s a film program without a single example of Luis Buñuel’s works? There’s almost no chance that you haven’t been told to study at least one film by the Spanish great. Most obviously, there’s the surreal short Un Chien Andalou. In recent years, a lot of Buñuel’s latter experimental works have been given the proper attention. In fact, a chunk of his straightforward dramas from within the ‘50s and ‘60s have been taught.

A film that encapsulates all of these parts of his career is Viridiana. It’s darkly to-the-point at first (in a neorealist sort of way). It then ventures into near-dream-like territory, as if your mind is collapsing from grief. It also exercises its use of black-and-white imagery extremely well. There simply is so much to take away from Viridiana, because it’s a turning point that Buñuel was aware of and exploited.

10. Wait Until Dark

I know many films on this list are considerably underrated, but it’s an absolute joke how overlooked Wait Until Dark continues to be. This thriller thrives on its bonafide performances, which you can argue is more relevant in theatre classes (unless you’re looking at this from a screenwriting angle). However, we could easily deconstruct the simplicity of this thriller.

It mostly takes place in one single location during an evening. A blind woman trying to work her way out of a home invasion heightens tension through some serious dramatic irony (what she is unaware of but we are able to see). This is all about maximizing minimalism; this is seeing how much can be done with just the barest of necessities in a film.

This isn’t Dogme filmmaking by any stretch (I’m sure there are many of those being studied), but it’s just a great, underseen example of how a film doesn’t need to be complicated to tick off all of the boxes. That makes the film a great starting point in many introductory classes, because all of the essentials are easy to spot.