5. Bicycle Thieves (“Ladri di biciclette” Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

One of the essential films of Italian neorealism, and perhaps the most famous, “Bicycle Thieves” is a quintessential example of the ideas behind the movement. Italian neorealism was born from an extraordinary conjunction of events: Italy had emerged from the war a destroyed country facing dire poverty, and, even upon the rumbles of their country – or precisely because they were there – filmmakers felt the need to tell the stories of the normal people facing such hurdles.

Joining this desire with the logistics limitations of the time, Italian neorealism put forth his principles: to shoot in real locations using real people (non-actors) in search for a greater realism, of a more humane cinema. “Bicycle Thieves” is a glorious proof of concept of this idea.

It used non-actors and real locations to tell a story about the resilience of family, and of the heroism of the common man. Honest, simple and brilliant, it’s a work of such elegance and intelligence that watching it becomes an act of bonding with the human experience. It showed the possibilities of a different kind of cinema, and is still today a perfectly crafted movie, capable of, as De Sica put it, “uncovering the drama in everyday life.”

4. The Seventh Seal (“Det sjunde inseglet” Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

Even among the greatest filmmakers, Bergman stands on a place of his own. His output is so vast and impressive that it’s hard to believe one filmmaker could produce it all, and over the years, its influence touched filmmakers everywhere. It’s easy to understand why: his work is a testament to the power of storytelling and the unique ability of cinema to reach far into our deepest fears and desires.

“The Seventh Seal” is one of its greatest, perhaps its most influential film, and an invaluable lesson in the absolute mastering of narrative. The scene in which the Knight plays chess with Death is one of the most recognizable and memorable in movie history, and it sets the tone for an extraordinary visual exploration into the meaning of existence and man’s desire to find it.

3. Breathless (“À bout de soufflé” Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

Upon watching “Breathless,” one can only wonder what anyone would think of the movie at the time it was premiering in theaters across France. Seeing it today, already used to cinema that took ideas from the Nouvelle Vague, it’s hard to imagine the sheer impact of its ideas. It was the time of a new generation in France, one that, eager to break the rules of the previous one, erupted from the Cahiers du Cinéma. But none personified the Nouvelle Vague spirit as well as Jean-Luc Godard.

Willing to forsaken all narrative to deconstruct a movie to his most fundamental essence, he was already a true maverick, whose name would become synonym with cinema. The shooting of “Breathless” was so chaotic and Godard’s vision so unusual that Jean-Paul Belmondo, the lead actor, believed the film would never be released. He was wrong, and in a drastic way: it was a massive success and one of the films that would make him famous.

In a way, it embodied Godard’s spirit: it’s frantic, powerful, unafraid to take risks, and it plays like a ride to an unexpected place – a shining example of the Nouvelle Vague desire to break the rules, and a monumental piece of filmmaking.

A bold exploration of unconventional narrative, of bending the rules, eager to find a new way to tell stories, it felt like a blow coming out of nowhere for directors at the time and it gave a pure, untouched breath of life into cinema.

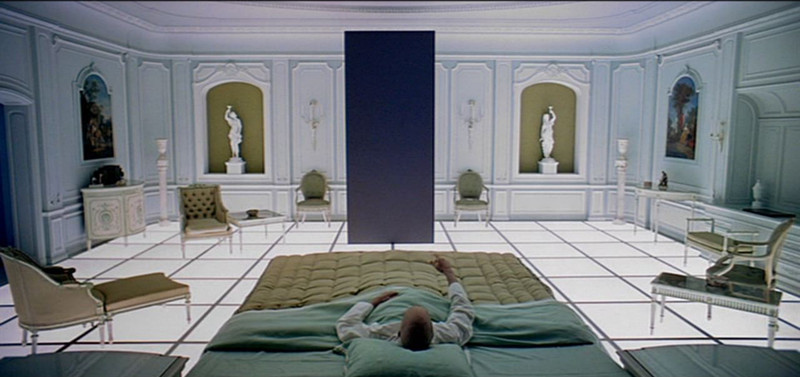

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

The opening shot alone is a ode to cinema, and states the movie’s ambition from the start. A voyage into the deeps of space and of the human soul, “2001” is an impressive achievement and shows Kubrick at the top of its skill, commanding with authority an endeavor of epic proportions. It’s a movie that showed a glimpse into the future, revealing the universe as it had never been seen before.

Beyond its extraordinary visual narrative, amazing set design, scientific accuracy and stunning cinematography, it is the movie’s gaze into space that sets it apart from anything else: the sense of infinite, the story of mankind told across time and space, from the discovery of tools until the ability to built machines able to travel into the sky and beyond – a jump to a new millennium told in one of the most brilliant moments of editing in cinema history.

It showed the potential of science fiction as the means to build unexplored worlds, to present it to the audience’s eyes. And if that wasn’t enough, the danger of artificial intelligence, man vs. the machine, told in the way only Kubrick could. A work of extraordinary vision, “2001: A Space Odyssey” is a breathtaking moment in cinema history, and an unforgettable look into the future of film.

1. Stalker (“Сталкер” Andrey Tarkovsky, 1979)

Bergman once said, “Tarkovsky is for me the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.” To receive such a praise from Bergman is no easy feat, but upon watching his films, one understands the admiration.

If cinema can be pure poetry, Tarkovsky was the closest one to achieving it. His movies are never about what an image means, but about what an image can mean. Open to interpretation, to free will, his images create a cinematic work of marvellous density and a deep connection with the human experience.

And among all of Tarkovsky masterpieces, “Stalker” is the one where this harmony between poetry and image is more evident: the story of an exploration into the “zone,” a place of mystery in which one can find the answers to their desires, but where the characters find the questions in which their existence is built, embarking in a mediation about themselves – and mankind. Playing as a dream, reaching deep into the very soul of cinema, revealing all of its possibilities as the true language of our thoughts, “Stalker” is cinema at its purest form.