One of the qualities that makes cinema such a beloved art form is its ability to provide pure escapism for the audience, transporting them into a glorious Technicolor world where problems and worries can be put aside for a couple of hours and you can walk away from the cinema in a happier state of mind than when you went in.

The most obvious way to make the audience feel happy is to make them laugh and fill the scenes with an abundance of feel-good moments but the wonderful variety of the cinema means that this isn’t the only way to lift our spirits. It can be equally joyful to watch a director enjoying their work and displaying a clear passion for the art of moviemaking, and to watch films that have astute observations on the reality of life. As Fellini remarked about cinema – “There is no end. There is no beginning. There is only the infinite passion of life”.

Here are ten films to put you in a great mood.

10. Sullivan’s Travels (1941)

Renowned playwright Preston Sturges proved he was also a distinguished director with his comedic masterpiece about the journey of self-discovery that movie-director (Joel McCrea) embarks upon.

Fed up of churning out shallow films such as Ants in your Pants, the eponymous John Sullivan (McCrea) demands to his studio superiors that he wants to focus on films with ‘Stark realism – that depict the problems that confront the average man.’ ‘But with a little sex?’ the studio bosses enquire back. Whilst keen to indulge their prized director, they point out that he has no experience of suffering in order to make such a film, and so Sullivan takes to the great outdoors, disguised as a hobo.

The dialogue is razor sharp throughout, and there are frequent moments of great hilarity regarding the bus of helpers that the studio has hired to trail Sullivan and keep him safe. It is moments like this where Sturges’ satire really comes to life, his mocking of Hollywood and all its oddities managing to feel both highly amusing and acerbically critical at once. Whilst the plot can occasionally veer into ultra-contrived territory, Sturges’ supreme gift for characterisation ensures that the story remains somehow believable, and many of the characters he crates, such as Veronica Lake’s unnamed heroine, linger long in the memory.

Eventually Sullivan, after witnessing the happiness a simple Disney cartoon brings to members of a labour camp, comes to realise the merit of laughter as a mechanism to enrich people’s lives. This is perhaps Sturges’ way of questioning the merit of pretentious, high-art cinema if it is only driven by its own sense of artistic achievement, and indeed the mocking of Hollywood would suggest this, but even without considering such social commentary, ‘Sullivan’s Travels’ is a hilarious, enjoyable classic.

9. Bande a Part (1964)

Jean-Luc Godard is at his nonchalant, genre-defying best with Bande a Part’, a playful examination of cinema itself as much as it is a subversive heist film. We follow Franz (Sami Frey) and Arthur (Claude Brasseur), two aimless Parisian locals who spend their time play-acting/mimicking the Hollywood classics (in a nod to Godard himself), and chasing the beautiful Odile (Anna Karina). She tells them about a cash fortune hidden at the house where she works, and the three of them hatch a rather half-baked plan to steal it for themselves.

There are a trio of brilliant scenes that stand out as testament to the freewheeling inventiveness of early-career Godard. The first sees the trio run out of conversation at a café, and agree to a minute of silence. Rather jarringly, it is the real deal, Godard quite literally cutting everything from the sound design, rather than just hearing the background noises of the café. It’s a bold and amusing way to remind the audience of the artifice of the art form they’re watching.

The second scene sees the trio break out into a spontaneous, co-ordinated dance routine in the café, in a much beloved sequence that has been copied and imitated ever since. What makes the scene particularly inventive is Godard’s use of a voiceover at various points to interrupt the music and explain the thoughts of the protagonists. The third brief scene sees the would-be criminals killing time by attempting to do a tour of the Louvre in record quick time, rushing past the famous paintings in a jubilant blur.

Whilst it may not have the same philosophical and narrative weight as other Godard classics, it is infectious to watch one of the great auteurs clearly having so much fun with his work. His cavalier approach to film-making is evident throughout, and makes for a joyous experience for the audience as they are taken along for the ride.

8. Amelie (2001)

‘Amelie’ was an international sensation upon release, managing to be a rare example of a foreign language film that resonated in the English-language world as much as its domestic market. Featuring a breakthrough performance from the utterly charming Audrey Tatou, the film sees Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s gift for world-building put to its best use, crafting a visually unique modern-day Paris.

Unlike the more outlandish worlds he created in ‘Lost City of Children’ and ‘Delicatessen’, the Paris here is closer to real life, but sprinkled with a little magic from the active imagination of the eponymous Amelie. She is a highly shy waitress, struggling to escape from the shackles of a childhood spent in isolation following the death of her mother. After a chance accident leads Amelie to a discovery that brings happiness to a stranger, she makes it her life mission to improve the lives of those around her.

The exuberant cinematography of Bruno Delbonnel brings the eccentric inhabitants of this world to life, and it is a delight to see their positive interactions with Amelie play out before us. However, it is Audrey Tatou who is really the star of the film, and her careful, nuanced performance provides depth and emotion to Amelie, elevating her beyond mere saccharine cliché. When the roles are reversed and it is finally time for the world to give Amelie her happy ending, it is one of cinema’s great uplifting moments.

7. Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring (2003)

Kim Ki-Duk’s enchanting Buddhist film about the circle of life is beautiful in its simplicity, having a hypnotising effect that lingers in the memory long after the film has finished. Shot at a single location by cinematographer Baek Dong-hyeon, ‘Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter… and Spring’ focuses on a Buddhist monastery in the Korean forest wilderness over a number of years, calmly observing the lessons of life that a young apprentice learns under the detached guidance of an elder Monk.

The film begins with the young monk exploring his environment in the springtime and behaving mischievously under the watchful gaze of his master. His antics descend into more troubling and sinister behaviour, and upon witnessing his cruelty towards animals, his master teaches him a strict lesson about having respect for all living things.

The following seasons are explored approximately a decade apart, as the young apprentice struggles with his adolescent hormones around a young woman, and eventually sees his childish bad behaviour develop into far more serious territory. In certain ways the film presents a pessimistic inevitability to the cruelty of man, and the suffering he inflicts upon the world. Yet the film is far more than this gloomy message, and the final shot of the Buddhist statue Maitreya, the prophesised future God who will revitalise Buddhist teachings, overlooking the monastery suggest a path to redemption exists to escape this cycle.

Ki-Duk’s unsentimental, naturalistic style and the gentle repetitions of character arcs and seasonal cycles combine to give ‘Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter… and Spring’ a sense of peaceful spirituality. It is a film with a beguiling, transcendental quality, and perhaps the closest cinema has come to a truly meditative experience.

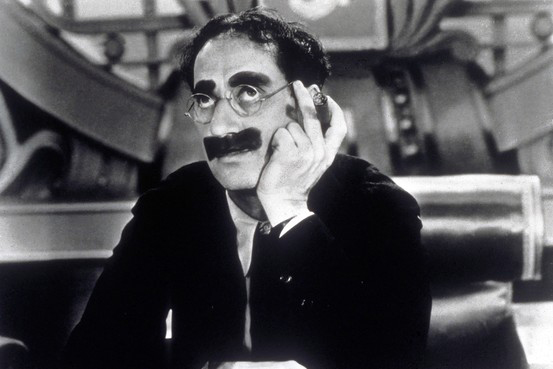

6. Duck Soup (1933)

Representing the pinnacle of the Marx Brothers’ career, ‘Duck Soup’ is an exhaustingly hilarious experience, and a triumph of their anarchic, vaudevillian comedic vision. Part political satire, part absurdist farce, its exploration of war, and the fragile ego and petty hubris of the dictators behind it still feels as relevant today as it would have on its interwar release date.

Groucho Marx’s Rufus T. Firefly makes us laugh from his very first moment on screen, and his rapid-fire one-liners set the tone for what is to follow. It is a relentless barrage of comedy; the style ensuring that even if some jokes do not land, you are too busy laughing at the next one to notice. Whilst the script is extremely funny by itself (“all you need is a Rufus over your head”), it is Groucho’s mischievous, withering delivery that really brings it to life.

Due to some thoughtless decision making, Firefly is appointed new leader of Freedonia, and his brazenly chaotic and uncivilized governing style soon provokes trouble with neighbouring Sylvania. To capitalise on Freedonia’s instability, their ambassador hires two hapless spies (Chico and Harpo Marx) to observe Firefly. Harpo’s mime-inspired demeanour is the perfect foil to Chico’s wise-cracking, phoney-Italian shtick, and their slapstick madness is brilliantly constructed. Rather surreally, Chico disguises himself as a peanut salesman, and his and Harpo’s unnecessary tormenting of a rival merchant is a particular highlight.

However, it is the mirror scene that is most fondly remembered from the film, and indeed it is a classic of 20th century cinema. In the escalating pandemonium of the march to war, Harpo – dressed up as Firefly – finds himself in a position where he has to convince Firefly that he is staring into a mirror, and not at him. Showcasing the very best of physical comedy, it’s a highly inventive set-piece, and a perfect example of the Marx brothers’ genius that underpins the comedic chaos unfolding in front of us.