5. Audition (dir. Takashi Miike, 1999)

Shigeharu Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi) is a recent widower in search of a new life partner. In order to help him, his friend Yasuhisa (Jun Kunimura), who is a film director, suggests that they stage an audition for a female role in a supposed new film, so that he can choose among the actresses that will come to the audition.

Shigeharu’s eye is caught by a sweet-looking girl, Asami (Eihi Shiina), and the two of them begin to date. Soon, though, he realizes that something strange is going on with Asami, who ends up more mysterious and “dark” than she seemed at first. What comes next will be beyond the man’s (or the audience’s) initial expectations.

Takashi Miike’s adaptation of Ryu Murakami’s book of the same name starts out as a domestic drama of an eerie atmosphere, soon to be transformed into a gritty J-horror shocker that established the Japanese director’s reputation outside Japan and really caught the world’s attention.

As a proud representative of the (brilliant) uncompromising Japanese horror’s fame, “Audition” is a raw, limit-pushing picture with graphic violence and torture scenes on the verge of absurd that tests the audience and is enough to please fans of the genre, to say the least.

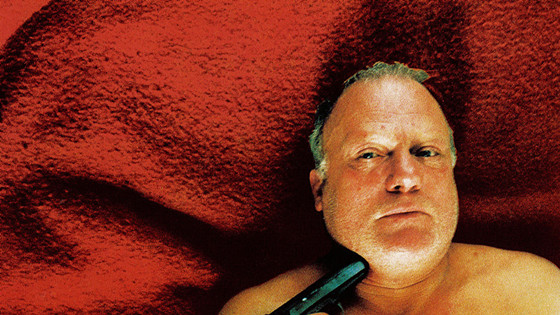

4. I Stand Alone (dir. Gaspar Noé, 1998)

A horse meat butcher (Philippe Nahon), who is a single father to a disabled child, is sentenced to prison for assaulting somebody who he mistakenly thought had abused his daughter. After being released several years later, and having lost everything, he struggles to regain what he can by finding a job and a new girlfriend.

The attempt to rebuild his life, though, stumbles upon a ruthless modern society with no real compassion and concern about those in actual need of it. Although the Butcher is trying to act accordingly, get a job, and resist his unorthodox thoughts and impulses, he always ends up in rejection, isolation, and misery.

Before the fuzz and controversy of “Irreversible,” Gaspar Noé had shocked the world with his far more hardcore and deeply disturbing debut feature-length film, “I Stand Alone,” which was a sequel to his 1991 short “Carne.” The themes and brutality presented in “I Stand Alone” managed to upset and even disgust audiences, a lot of whom found it appalling.

The true violence, however, in the French director’s film lies in its non-action and silence. In the quiet despair of a man who can’t fit in no matter what he does. Who is constantly treated as outcast. Who is unemployed, unloved, whose mind tortures him, whom society quarantines, whom people detest. Who is alone.

And the size of this loneliness that mutilates the soul cannot be measured or evaluated. It can only be experienced. It can only be captured in the simplicity of lyrics like E. E. Cummings’ “and May came home with a smooth round stone, as small as a world and as large as alone.” It can only be displayed with the – not profound, yet evident – sensitivity that emerges from Noé’s disturbing but also heartbreaking film.

3. Come and See (dir. Elem Klimov, 1985)

In 1943 Byelorussia, Nazi German troops have occupied the region. The film follows a teenage boy named Florya (Aleksey Kravchenko), who leaves his family to join the Soviet resistance movement. Through the eyes of the young partisan who is determined to fight and survive, we witness the pain and atrocities caused by the Nazis during the Total War, like the destruction of entire villages in Belarus. One such village is Florya’s village.

Through its realistic and fearless depiction of war’s immense cruelty and man’s capability of inhumane cruelty per se, “Come and See” is not so much an anti-war film, but rather a bold attempt to tell the truth about a specific war – a truth the world needs to acknowledge, tell, and remember, as raw as it is.

The look on the protagonist’s face is perhaps one of the most haunting in the history of cinema, and Elem Klimov’s film is a two-and-a-half-hour nightmare that keeps you on the edge of your seat, anxiously waiting for redemption. And like any real story about the victims, when redemption does come, however compensating by nature, it doesn’t “allow” you to feel any better

“Come and See” is, undoubtedly, a film that everyone should watch.

2. Oldboy (dir. Park Chan-wook, 2003)

Oh Dae-su (Min-sik Choi) is kidnapped and held captive in a cell for 15 years, without knowing who his captors were or why he has been enduring this torture. After being released, Dae-su has five days to track down his captors in order to take the revenge he was planning for all these years, find out the reasons for his imprisonment, and also reunite with his daughter. In the meantime, he meets a young girl, Mi-do (Kang Hye-jung), who is a chef at a sushi restaurant, and the two of them fall in love.

Park Chan-wook’s neo-noir is based on a manga of the same name by Nobuaki Minegishi and Garon Tsuchiya, and is by far the most exciting part of the director’s vengeance trilogy. More or less loosely inspired by the story of Oedipus Rex, this captivating Korean drama blends tragedy and revenge as masterfully as it can get.

Its violence and brutality, no matter how extreme at times, have such a dynamic role in the film’s story and cinematic structure, that the outcome is a beautiful dark, sadistic film that’s rarely seen. “Oldboy” succeeds in shocking the viewer in the genuine, powerful way that Asian horror cinema can do better than anybody.

1. Cannibal Holocaust (dir. Ruggero Deodato, 1980)

An American film crew consisting of four people disappears in the Amazon rainforest, while trying to film a documentary about some of the forest’s cannibal tribes. Professor Harold Monroe (Robert Kerman), who is an anthropologist, visits the rainforest on a rescue mission for the missing crew.

As time passes, the professor and his guides manage to approach the local tribes, gain their trust, and ultimately get them to agree to give them the footage left behind by the film team, only to find out that the crew had been treating the natives with disrespect and cruelty in order to shoot an exciting documentary.

Ruggero Deodato comments on his film on the relationship between primitive tribes and the civilized West, a relationship not based on mutual respect and the attempt to understand one another, but rather on suspicion and defense on the native’s side, and bloodthirsty exploitation on the West’s side. And if he holds one of the two responsible for the blame, it is clearly modern societies.

Much is disturbing about Deodato’s film. Its brutal representation of cannibalistic violence and sexual assault, as well as the real depiction of animal cruelty and the usage of real members of indigenous South American tribes along with the actors, shocked the audiences and led to great controversy concerning the film.

Not only was “Cannibal Holocaust” banned in several countries, but the Italian director was also arrested on obscenity charges. Additional charges were made due to rumors, according to which, actors were killed during the shootings were also pressed on Deodato, for which however he was later found not guilty. All in all, he created a film that became itself a typical example of the savage, exploitative sensationalism he originally intended to criticize, and that alone is enough to explain the film’s huge impact today.

Honorable Mentions: Freaks (dir. Tod Browning, 1932), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (dir. Tobe Hooper, 1974), A Clockwork Orange (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1971), The Exorcist (dir. William Friedkin,1973), A Serbian Film (dir. Srdjan Spasojevic, 2010), Nekromantik (dir. Jörg Buttgereit, 1987), Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (dir. Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975), Strange Circus (dir. Sion Sono, 2005), Tetsuo, the Iron Man (dir. Shinya Tsukamoto, 1989), Begotten (dir. E. Elias Merhige, 1990), Martyrs (dir. Pascal Laugier, 2008)