5. The Greatest Show on Earth (1952)

Cecil B. DeMille was one of the first directors, preceding the likes of Hitchcock, Spielberg and Cameron, to land himself a brand name that signified ‘event movie,’ with a string of hit films that ranged from the silent era all the way through the excessive use of cinemascope. He was a name that signified spectacle and wonder like none could rival at the time, with critics and audiences unanimously praising him.

Yet strangely enough, the movie for which he eventually won the Best Picture Oscar was one of his most mediocre – the circus drama “The Greatest Show on Earth” – a feat even more unforgivable when you considered it beat out fellow movies such as “The Quiet Man,” “High Noon,” or the bonafide classic “Singing in the Rain.”

Certainly, at the time, the novelty of having a film based around the behind-the-scenes spectacle of a travelling circus seemed appealing, yet the close to three hour length is saddled with documenting these performing acts ad nauseam, with only a rote and infuriating love triangle set between Betty Hutton, Charlton Heston, and Cornel Wilde being the only discernible soap opera-ish plot, in an experience that’s unanimously called out for being the ‘worst film to win Best Picture.’

Where the film succeeds, though, is in DeMille’s penchant for shooting the stunning spectacle and stunt-work of the performance acts; despite us having zero interest in the actual plot, the selling point of the circus itself is a visual feast, not to mention an impressive time-capsule piece.

4. Revolver (2005)

Before he became the ’Sherlock Holmes’ guy, Guy Ritchie was the ‘British gangster’ guy, a moniker he became pigeonholed after his breakthrough hit with “Snatch”; a former attempt at moving against convention led to his unfortunate effort with then wife Madonna in “Swept Away,” a messy rom-com.

After toiling away with some time off, Ritchie returned to the genre he was fatigued by in an attempt to rejuvenate it in this surreal piece that devolves into painfully head-scratching and self-important pathos.

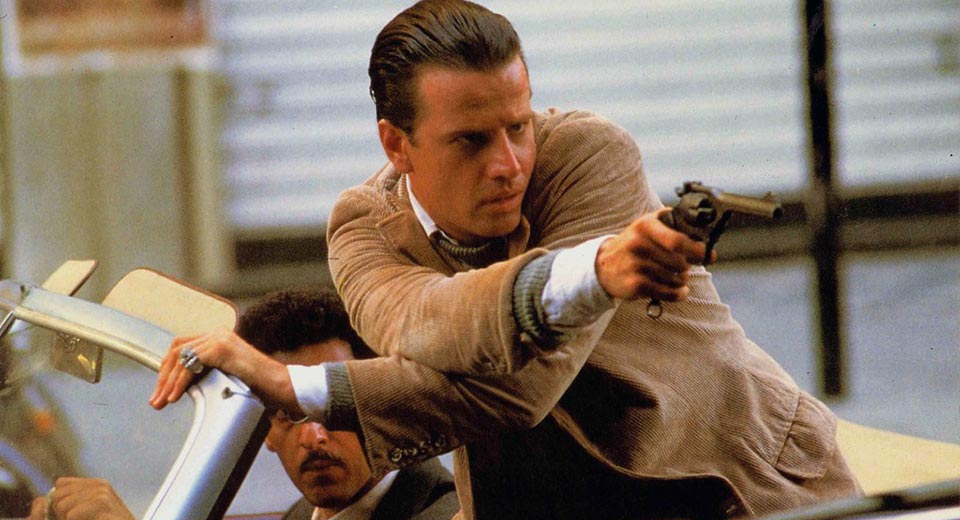

Greasy mullet-sporting ex-con Jason Statham gets embroiled in a game of ‘chess’ against a shouty and bronzed mafioso Ray Liotta, with plenty of deep voiceover musings and a obligatory random ‘anime’ sequence (“Kill Bill” was all the hype back then). Things spiral toward an ending you’ll be hard pressed to know if even Ritchie make sense of it, although most would be hard pressed to care at that point anyway.

As perplexing and frustrating as the film is, one would be hard pressed not to be floored by its finesse in imagery; in fact, from a strictly superficial aesthetic it’s one of Ritchie’s most impressive and rich movies. He experiments with colours that the gritty palette of his other films limited him from, successfully creating a heightened grey-skied fantasy world where criminals are pitted against each other in battles of wit.

Ritchie deploys all manner of compositional and editing techniques to create a handful of strong set pieces – the failed restaurant assassination attempt, and Mark Strong’s no-nonsense hitman taking out a bevy of enemies in a warehouse showdown. If all the overcomplicating nonsense plot was cut out, there was an opportunity for Ritchie to make a taut and efficient thriller, yet for the most part, he seemed to get in his own way in this much maligned effort.

3. The Sicilian (1987)

Despite Michael Cimino’s rocky career, you could never fault him for aping other filmmakers, but with “The Sicilian,” Coppola’s influence not only casts a giant shadow over all proceedings, it was the film’s blatant selling point.

Superficial comparisons can’t be avoided, as it’s an adaptation of a Mario Puzo novel centred around the ins and outs of the Italian mafia world, but also its stylistic approach – big-budget and operatic – feels a little obvious for the usually distinct Cimino.

The plot focuses on Italian revolutionary/folk-hero/zealot Salvatore Giuliano (Christopher Lambert) set in the scenic island of Sicily (imagine Michael Corleone’s Italian set chapter in “The Godfather” for more than two hours and you’re not far off).

Cimino shot on location and the glorious visuals truly stun. The man is at his element when it comes to cinematography and mise-en-scene, but sadly the rest is horribly lacking – he missed Coppola’s most important ingredient with the the ‘Godfather’ saga, the authenticity of his actors. Making a spaghetti epic with a mixed European/American cast truly grates and the stilted script only comes across more wooden with its awkward accents and forced English dialogue.

No one is more guilty a culprit than the woefully miscast Lambert as the Sicilian lead character. It doesn’t help the story itself never gives him any dimensions or relatability, playing the controversial figure as a bizarre cross between a superhero and a Jesus Christ figure.

The only actor who walks away with a semblance of dignity is a young John Turturro as Giuliano’s right-hand/Judas. Though he struggles with the material at points, he still manages to bring a level of humanity and gravitas to the film where the rest is lacking (its a grand shame they didn’t place him as the lead instead).

Still, there are moments when things come together beautifully – an innocent protest ending in a shocking massacre, a harrowing execution scene of Giuliano’s betrayer – but ultimately the weak elements tip the boat too often, resulting in a film that should’ve worked but sadly doesn’t. Still, it’s worth a watch as interesting failure in Cimino’s career – it’ll just impress more if you play it on mute and eat up the visuals instead.

2. Only God Forgives (2013)

Coming off of his biggest hit in a fairly low-key arthouse career, Nicolas Winding Refn was put between a rock and a hard place. “Drive” was not just a sleeper hit but a cultural phenomenon, and suddenly a massive spotlight sat on the underdog director and he felt pressure to successfully follow up on it.

Yet he also felt pressure to subvert commercial expectations, and as a result his movie is left in a weird purgatory like state that just stagnates – not content on pleasing the crowds yet formulaic enough to feel stale, it reeks of confused pretension as a nonsensical plot moved at glacial pace with nowhere much to go. “Drive” star Ryan Gosling simply walks through rooms looking blankly at walls as do the rest of the cast; only Kristin Scott Thomas appears to be having any fun as the tough love matriarch.

Refn has done slow and atmospheric several times, but there was at least a feeling of purpose to his dream logic. Not so much in this shallow time waster. Yet like all Refn films (post-“Bronson”), his visual palette and cutting style of neon compositions are stunning – part Bava, part Kitano, all gorgeous. In fact, if you took any five minute moment of this movie on its own, it’s feast for the eyes, but hanging out a minute longer will be a true test of endurance.

1. Sucker Punch (2011)

Zack Snyder is a controversial figure amongst film fans; certainly his earlier films had him joined with fantastic source material, such as James Gunn’s clever remake of “Dawn of the Dead” or Frank Miller’s epic comic “300,” which were entertaining efforts coupled with stylised polish. So what happens when Snyder writes his own screenplays? Painful storytelling, it seems, with this messy movie centred a group of attractive women kicking stylish ass in a number of video game-like scenarios.

The film had all the elements for being an enjoyable guilty pleasure to watch with the lads, but Snyder, taking his first (and one wishes last) screenwriting credit, manages to make the plotting so painfully pretentious and self-important that this surefire slam-dunk becomes a grating chore to sit through.

The visuals, however, are out of this world, throwing in some incredibly inventive action scenarios that throw everything but the kitchen sink at us. Want Nazi cyborgs in trench warfare? Or gargantuan samurai monsters? You got it! The battles and polished world building are some of Snyder’s’ most impressive pieces of eye candy to date. It’s a painful shame the script he couldn’t give the those pretty pictures substance, a discernible plot, or any less pretension in a chore of a movie.