Every artist is apt to dip into the well of poetry and prose for inspiration, but sometimes a direct visual reference is desired; a pastiche of the masters that came before. As great filmmakers have inspired modern painters, so to have great painters influenced the mise en scène of directors and cinematographers throughout the history of cinema.

Paintings are often recreated as a brief on-screen homage, but these static works of art have also informed the structures and themes of entire scenes, and in some cases, complete films. The following list compares scenes from thirteen films with the paintings that directly inspired them.

1. Dreams (1990), Akira Kurosawa | Wheat Field With Crows (1890), Vincent Van Gogh

The fifth vignette in Kurosawa’s film has fellow director Martin Scorcese refining his Queens accent to portray Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh. We experience this segment through the daydream of an aspiring artist who finds the great painter sketching at his easel in a wheat field. After explaining how he came to lose his ear, Van Gogh tells of his urgent need to paint as much as possible before the daylight fades.

Kurosawa, 80 years old at the time, makes a clear metaphor here in relation to his own artistic ambitions – he went on to make two more films after this. The sequence transitions to the aforementioned dreamer literally walking through several other Van Gogh paintings before coming back to the wheat field, where a flock of crows scatter into the azure sky.

2. Shirley: Visions of Reality (2013), Gustav Deutsch | New York Movie (1939), Edward Hopper

Spanning three decades in the life of the eponymous character, viewers are presented with a feature length homage to Edward Hopper, which also explores the culture and zeitgeist of mid-twentieth century America. With incredible attention to detail, thirteen of Hopper’s paintings are brought to life in this extraordinary indie film by director Gustav Deutsch, and cinematographer Jerzy Palacz.

The featured scene has main character Shirley (Stephanie Cumming) leaning back against a wall to mimic the bored theater usher in New York Movie. Both images express a sense of disinterest or ennui; common motifs in Hopper’s work.

3. The Mill and the Cross (2011), Lech Majewski | The Procession to Cavalry (1564), Pieter Bruegel

After setting up the intricate details of Bruegel’s masterwork within a single shot, director Lech Majewski strings his film together in a series of vignettes dramatizing the everyday life of peasants depicted within the painting. These stories are broken up with intermittent monologues by other characters, including Bruegel himself (Rutger Hauer).

Although lacking a compelling narrative, this Polish production is a stunning feast for the eyes, faithfully rendering the atmosphere and period detail of The Procession to Cavalry.

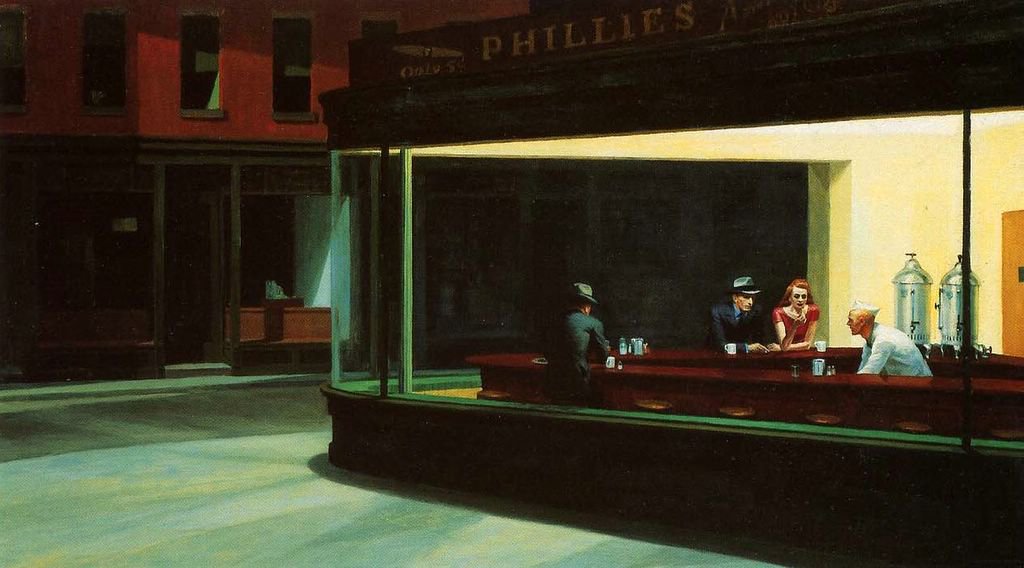

4. Pennies From Heaven (1981), Herbert Ross | Nighthawks (1942), Edward Hopper

Although critically praised, Herbert Ross’ film was a financial flop, grossing less than half of its total budget. Lead actor Steve Martin attributed this to philistine audiences being unable to accept him in a serious role,

“… the people who get the movie, in general, have been wise and intelligent; the people who don’t get it are ignorant scum.”

For audiences more appreciative of the finer things, director Ross and cinematographer Gordon Willis served up a veritable cinematic buffet. Set in depression era Chicago, the film features four recreations of famous paintings, with the centerpiece being a spot-on tableaux vivant of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. Those with a keen sense for detail will note that Hopper completed his piece eight years after the events of the film take place, and that his diner scene is set in New York, rather than Chicago.

5. The President (1919), Carl Theodore Dreyer | Whistler’s Mother: Arrangement in Grey and Black (1871)

For his first feature, the great Danish filmmaker Carl Theodore Dreyer adapts a novel (Der Präsident, by Karl Emil Franzos). Dreyer’s obsession with staging details would become a staple within his films.

With his camera patiently lingering on the composition, actors and sets are arranged within spartan, yet carefully composed scenes. Dreyer intentionally used his sets to convey the dispositions and emotions of his characters, rather than relying entirely on the performances of the actors themselves. In his letter to film critic Erik Ulrichsen, the director stated,

“… the surroundings should reflect the personality of the characters, while at the same time striving for simplicity.”

Such is the case with this scene from The President, whereby the set pieces and positioning of actress Jacoba Jessen reflect that of Whistler’s Mother. Dreyer was explicit regarding his admiration of Whistler, and the quiet intensity of this great artist’s work is repeated throughout the film.

6. Marie Antoinette (2006), Sophia Coppola | Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801), Jacques-Louis David

Sophia Coppola chooses to portray her subject as a naive young woman, ignorant of the growing resentment and revolution that eventually destroyed her. The young queen, as played by Kirsten Dunst, is thrust into a life she was wholly unprepared for.

During the film’s denouement, as the angry mobs crash the gates of Versailles, an image of Napoleon flashes on screen. He is seated on his horse, rearing back in a victorious pose that mirrors the famous painting by Jacques-Louis David. In what may be intended as a momentary erotic fantasy, the infamous Frenchman is portrayed by the actor who also plays Antoinette’s lover in the film (Jamie Dornan).

As with David’s painting, Napolean is depicted as an overtly masculine and handsome young man, casting a lustful glance toward the viewer. Here, Coppola doubles down on the naivete of her titular character, who even in the last throes of her reign, struggles to imagine the reality of her situation.

7. Nymphomaniac (2013), Lars von Trier | The Dying Artist (1901), Zygmunt

Framed in a discussion between the characters Joe and Seligman, Lars von Trier informs almost every scene of his film with the idea of the lure. Seligman’s enthusiasm for fly fishing compares with Joe’s sexual lures to sate her own passions. But is Seligman what he seems to be? Joe constantly reminds him that she is not a good person, and that his sentiments will change once her story has been told. So to does director von Trier cast his own lure, with Seligman revealing his true nature once Joe completes her story.

Joe’s hedonistic desire for physical pleasure without the trappings of emotional investment speaks to the void of humanity – the void of non-existence or death – being the only way to end the suffering experienced in the so called mortal coil. von Trier’s shots of Joe and Seligman closely resemble Zygmunt Andrychiewicz’s The Dying Artist – an image of what is probably meant to be a manifestation of Death playing violin at the bedside of a young man. Did von Trier look upon Andrychiewicz’s painting only to see a fellow artist reckoning with his own mortality?